Voices from the Sylff Community

May 20, 2013

Japan’s Ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Salla Garský,1 a Sylff fellow at the University of Helsinki, used her Sylff Research Abroad (SRA) award to research the process of Japan’s ratification of the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court (ICC). She presents an objective explanation of why Japan’s ratification was prolonged until 2007 after voting for the Statue in 1998.

* * *

The Rome Statute creating the International Criminal Court (ICC) was adopted in 1998 by 120 countries, including Japan. Since 2002, when the Rome Statue came into force, the ICC has been a permanent and independent institution. Its establishment was a historical achievement that permanently conferred jurisdiction to punish the masterminds behind heinous crimes, including genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression. No one who commits these crimes will thus be able to escape the consequences.

However, the power of the ICC depends entirely on member states because it has no resources of its own to make arrests and is financed by the state parties. Therefore, it is important to study the ratification process of the Rome Statute and explore potential obstacles for states’ decision to join the ICC.

Japan acceded to the Statute fairly late. While most ICC member states had ratified it by 2003, Japanese ratification did not come until July 20072. The objective of my research in Japan was to gather empirical evidence to answer the question: Why did it take almost 10 years for Japan to join an institution that it presumably supported from the beginning? Literature on Japan’s accession to the ICC has thus far focused on the legal aspects3. My research is aimed at contributing a political aspect to this literature by analyzing different political motivations behind the ratification process. This short article discusses some of the findings of my research in Japan.

Although I am interested in the political aspects of the ratification process, it is impossible to deny the role of the legal aspects. When countries consider joining the ICC, amendments to national laws are usually necessary. The Japanese legal system is a mix of civil and common law, with civil law characteristics, adopted from the German legal system, dominating the system4. Japan’s ratification of the Rome Statute required the deliberation of three main legal issues.

First, Japan had to consider whether and how to accommodate the crimes under the jurisdiction of the ICC with the national Criminal Code, which is very specific and, as such, takes time to amend. As Arai et al. point out, Japan decided not to amend the Criminal Code because almost all crimes under the ICC’s jurisdiction, with a few, rather irrelevant exceptions, are already covered by Japanese laws.5

As Meierhenrich and Ko elaborate, another legal issue, related to the jurisdiction of the ICC, was Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution:

“Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”6

Because of this paragraph, legislating war-related laws was initially complicated, as this would imply the hypothetical possibility of Japan engaging in war-related activities. This obstacle, however, was overcome in 2004, when the Diet adopted a package of emergency legislation that enabled Japan to ratify the 1977 Additional Protocols of the Geneva Conventions.7

The last important legal issue was cooperation with the ICC, which Japan resolved by adopting the ICC Cooperation Law, consisting of 65 articles8. Altogether, the elaborate legal review of national laws and the Rome Statute, as well as the preparation of the ICC Cooperation Law, slowed down Japan’s accession to the ICC.

Besides legal questions, according to the interviews I conducted in Japan, the US policy on the ICC also delayed ratification. While the Bill Clinton administration was not enthusiastic about the ICC, the George W. Bush administration was openly opposed, starting a global campaign against the ICC and not hesitating to voice its dismay about the institution in bilateral and multilateral forums9. Since the United States is Japan’s most important ally, this US policy affected Japan’s willingness to join the ICC. The US opposition against the ICC started to ease after 2005, though, when the UN Security Council referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC. Shortly thereafter, Japan started to consider ratifying the Rome Statute.10

Another aspect that delayed Japan’s ratification of the Rome Statute was money. Due to its high gross domestic income, Japan was slated to become the main contributor to the ICC. Article 117 of the Rome Statute, defining the assessment of the contribution, left some room for interpretation, and Japan initially calculated that its contribution to the ICC would be 28% of the total budget.

Japan wanted to apply the UN ceiling of 22% to its ICC contribution, but the European Union hesitated to accept the proposal. Eventually, the ICC Assembly of States Parties approved the 22% ceiling, and ratification began to materialize.11

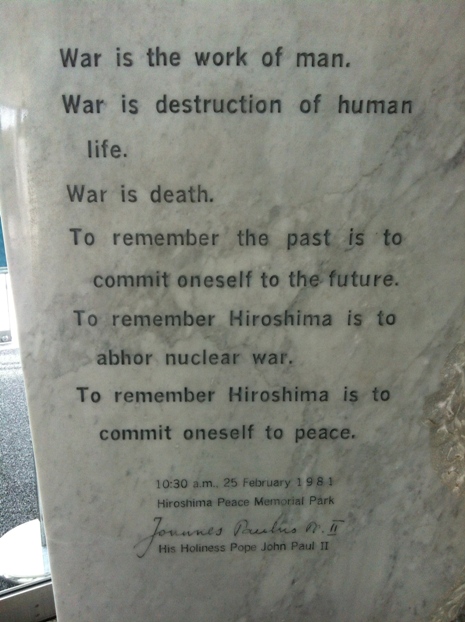

Words of Pope John Paul II to the people of Hiroshima, which have been the beacon guiding Salla's research.

To conclude, unlike the European countries, most of which wanted to join the ICC quickly in order to show their support for the new Court, Japan was not in a hurry to ratify the Rome Statute. Rather, Japan wanted to wait and see how the newly established ICC would develop before it joined. In general, there was not much political pressure in Japan to join the ICC, but the UN Security Council’s referral of the Darfur case to the ICC clearly had a positive influence on Japan’s decision.

The impact of the Jun’ichiro Koizumi administration on the ratification process has not yet been researched in depth, and this will be the subject of my future research. Tentatively, the delay in ratification can be explained in terms of the Japanese way of dealing with international treaties, which was described in many of the interviews I conducted.

Today, Japan is an active member of the ICC, and one of the Judges, Kuniko Ozaki, is Japanese. I hope that in the future, Japan will start to actively promote the ICC in Asia, as the region is clearly underrepresented in the organization.

1 I want to thank the Tokyo Foundation for making my research in Japan possible. I also wholeheartedly thank my Japanese advisor, Professor Mariko Kawano of the Waseda University’s School of Law, for allowing me to visit her institution and for her warm and most helpful guidance with my research in Japan. I am also grateful to Professors Shuichi Furuya (Waseda University), Akira Mayama (Osaka University), Osamu Niikura (Ayoama Gakuin University), and Hideaki Shinoda (Hiroshima University) for discussing and sharing their experiences regarding Japanese policy on the ICC with me and Keita Sugai (Tokyo Foundation) for his helpfulness. Furthermore, I am indebted to the Embassy of Finland in Tokyo, in particular Ambassador Jari Gustafsson and First Secretary Jukka Pajarinen, and the Delegation of the European Union to Japan. Lastly, I want to thank Juha Hopia, Suvi Huikuri, Sergey Kryukov, Riikka Rantala, and Asaka Taniyama for making my stay in Japan unforgettable. Unless otherwise mentioned, the opinions expressed in this paper are solely my own.

2 United Nations Treaty Collection, “Status of Treaties,” Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary-General, 2012. Available at: <http://treaties.un.org/Pages/ParticipationStatus.aspx> (visited March 8, 2013).

3 Kyo Arai, Akira Mayama, and Osamu Yoshida, “Accession of Japan to the International Criminal Court: Japan’s Accession to the ICC Statute and the ICC Cooperation Law,” Japanese Yearbook of International Law, 51 (2008): 359–383; Kanako Takayama, “Participation in the ICC and the National Criminal Law of Japan,” Japanese Yearbook of International Law, 51 (2008): 348–408; Yasushi Masaki, “Japan’s Entry to the International Criminal Court and the Legal Challenges It Faced,” Japanese Yearbook of International Law, 51 (2008): 409–426; Jens Meierhenrich and Keiko Ko, “How Do States Join the International Criminal Court? The Implementation of the Rome Statute in Japan,” Journal of International Criminal Justice, 7/2 (2009): 233–256.

4 Veronica Taylor, Robert R. Britt, Kyoko Ishida, and John Chaffee, “Introduction: Nature of the Japanese Legal System,” Business Law in Japan, 1 (2008): 3–8; CIA, The World Factbook: Legal System, March 5, 2013. Available at: <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2100.html> (visited March 8, 2013).

5 Arai, Mayama, and Yoshida, “Japan’s Accession,” p. 365ff.

6 The Constitution of Japan, November 3, 1946. Available at: <http://www.kantei.go.jp/foreign/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html> (visited March 8, 2013).

7 Meierhenrich and Ko, “Rome Statue in Japan,” p. 237ff.

8 Takayama, “Participation in the ICC,” p. 388.

9 John R. Bolton, “Letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan,” Digest of United States Practice in International Law 2002, Sally J. Cummins and David P. Stewart, eds., 148–149, Office of the Legal Adviser, United States Department of State (Washington, D.C.: International Law Institute, 2002); H.R. 4775, Title II, American Service-Members’ Protection Act (Washington D.C.: Congress of the United States of America, January 23, 2002); H.R. 4818, Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2005. Washington D.C.: Congress of the United States of America, January 20, 2004; Human Rights First, “U.S. Threatens to Cut Aid to Countries That Support the ICC,” December 7, 2004. Available at: <http://www.iccnow.org/documents/HRF_Nethercutt_07Dec04.pdf> (visited March 8, 2013); John R. Bolton, “American Justice and the International Criminal Court: Remarks at the American Enterprise Institute,” Washington, D.C., November 3, 2003; Philip T. Reeker, “Press Statement: U.S. Initiative on the International Criminal Court,” U.S. Department of State, June 13, 2000.

10 Masaki, “Japan’s Entry to the ICC,” p. 418ff.

11 Ibid., p. 415ff.