Voices from the Sylff Community

Aug 6, 2015

A Remembrance of Books Lost: Bengali Chapbooks at the British Library

The Research

This research is focused on the contested history of popular print culture in Bengal, India. Printing technology arrived in Bengal in the late eighteenth century, and the first Bengali books printed with movable type were translation of Christian tracts published under the aegis of the Baptist Missionaries of Serampore.

Although printing was at first controlled by the colonial authorities and the native elite, this “foreign” technology was quickly embraced by local residents, and a thriving publishing industry took shape in the nascent metropolis of Calcutta (now Kolkata), which soon became the second most important city of the British Empire.

The earliest printers were mostly humanists and scholars, but hack writers and pamphleteers soon entered the market with their cheap, entertaining books and crudely written pamphlets. Their target readers were mostly the newly created middle class and the semi-literate lower middle class.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the popular publishing industry became a headache for the colonial authorities and the native elite alike, who were offended by the bawdy contents of the cheap-print. Soon, they adjudged that the local publishing industry had to be controlled in order to inculcate a sound reading habit amongst Bengalis.1

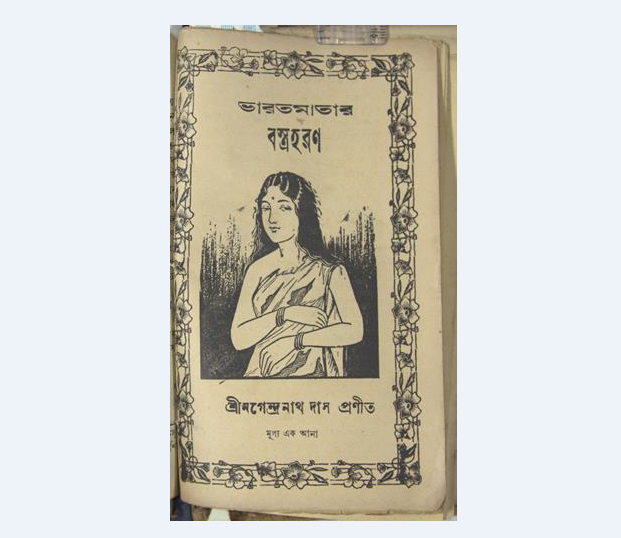

The title of this chapbook is Bharatmatar Bastraharan (The Disrobing of Mother India). Written during the Second World War, it describes how the general populace suffered due to an acute shortage of clothing material and other essential commodities during the years of conflict. The cover shows a picture of “Mother India” as a poor, yet beautiful woman who is wearing rags since she no longer has enough clothes to cover her body. This chapbook was written by prolific author Nagendranath Das, whose works were frequently banned by the British government.

The cheap publishing industry was first established around Battala in North Calcutta. Although this industry later spread to other parts of the state, the name “Battala” became synonymous with obscene and erotic printed material that soon became the target of the censoring authorities. While the Battala presses were persecuted in the nineteenth century for spreading salacious and corrupting ideas, subsequent historians have pointed out that these books represented the “native cultural elements” that the colonial authorities marginalized as part of their efforts to exercise “bio-political” control over the native mind.2

In the subsequent historiography of popular print culture in Bengal, Battala has been celebrated as the quintessential locale of subversion and resistance. This has also contributed to the rather misleading notion that the cheap publishing industry existed only to defy the elite print culture. While the pioneering work in this field done by such historians as Sukumar Sen, Nikhil Sarkar, Gautam Bhadra, and Sumanta Bandyopadhyay has unearthed a treasure trove of interesting material, it has, in turn, ensured that the books that were not so subversive in nature were buried underneath this “romance of defiance.” And in time, these books mostly vanished from the history of Bengali popular print culture.

My research for the SRA period was focused primarily on unearthing such material—chapbooks and pamphlets on topical events that acted as the conduit of information for the semi-literate readers who were not a part of the information network of the newspapers and periodicals published by the educated elite. During my Sylff Research Abroad in Britain, I endeavored to:

- Find chapbooks and pamphlets written on topical events

- Analyze their language to see how they used traditional modes of cultural expressions to entertain as well as inform and educate people about the modern world

- Understand the role they played as the mass media in the nineteenth century

The SRA award allowed me to look for these books in the vast archives of London’s British Library, which was the deposit library of the British Empire. It boasts perhaps the largest collection of nineteenth-century books published within the domains of the empire, and Bengali books were no exception. As a visiting researcher at King’s College London during this period, I also got the chance to speak with scholars and researchers from other institutions, such as the Institute of English Studies and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London and Oxford University.

The archival work was done at the Asian and African Studies Collection of the British Library, which houses the complete collection of the India Office Library. Conversations with Mr. Graham Shaw, the doyen of nineteenth century Bengali print culture, gave me crucial directions on the use of the vast archive. The books, on the other hand, presented unique stories, and I saw how natural disasters, scandals, incidents of legal or political importance, and other events were represented in the popular print media. And examination of these books is important for various reasons. First, the notion that the sole function of the Battala presses was to resist the cultural elite suggests that the marginalized print cultures did not have an independent existence. This, though, was far from the case.

Second, these books show that the colonial public sphere was more complicated than it is generally regarded. Nineteenth century chapbooks and pamphlets serve as important windows on the everyday life of colonial Bengal: a sociological examination along these lines has long been pending.

Third, an examination of these documents reveals that the main purpose of popular print culture was the same as that of elite print culture: dissemination of information.

My research during the SRA period was not limited to the study of these books, however. My other aim was to study the India Political Intelligence Department and the Crown Representative’s Records in order to find out how the British Secret Services tracked down seditious literature after the emergence of nationalist movements. Though most of the leading figures of the nationalist movements, both pacifist and extremist, were educated elites, they adopted the chapbook and pamphlet formats for the dissemination of their ideas. Due to the near invisibility and the ephemeral nature of these slender volumes, chapbooks and pamphlets became major carriers of subversive ideas during the period between 1905 and 1947.

The hack writers, in turn, appropriated nationalistic themes to increase the sales of their books, since books written on such themes were very popular. While doing my research in India, I had amassed a vast digital collection of nationalistic pamphlets and chapbooks printed between 1930s 1940s, and I needed to consult the India Office Records at the British Library to access many other similar pamphlets (especially those published between 1905 and 1930) and to examine the records of the Secret Services to understand how the authorities tracked down and persecuted the authors, book sellers, and at times even the readers of these items.

While the colonial authorities exercised stringent censorship to ensure that seditious ideas were not circulated, pamphlets and chapbooks written on nationalistic ideas spread rapidly through private vendors and dedicated revolutionaries, who also doubled as publishers. For this section, my research questions were:

- How were the seditious pamphlets and chapbooks produced and circulated?

- How did the censoring machinery of the colonial government function to control the dissemination of such ephemeral items?

- How did the hack writers appropriate nationalistic ideas in their chapbooks and pamphlets?

- Apart from the criticism of the colonial regime, did the writers comment on other aspects of the social condition? If so, how?

The Burden of the Archive

My research was enriched by everything that I studied during this period: chapbooks and pamphlets, legal records, court proceedings, and reports of the Secret Service agents who intercepted letters, followed booksellers, and sent spies to track down the people who distributed seditious materials during one of the most volatile periods in the history of the region.

While studying the pamphlets and chapbooks that described the partition riots and famine,3 I got a chance to read the disturbing memoirs of the English soldiers who were stationed in Calcutta at that time. The intense nature of the documents that I studied often left me greatly distressed, though this was also part of the thrill that is often associated with archival research of this nature. These findings have enabled me to develop a greater understanding of how this rustic information network functioned amongst the economically disenfranchised sectors of society, long before the coming of electronic media that made communication more democratic.

For this opportunity I am grateful to the Tokyo Foundation. The Sylff fellowship and the SRA award enabled me to fulfil the academic potential that my project had. I would also like to thank Professor Clare Pettitt of the King’s College London, Mr. Graham Shaw of the Institute of English Studies, University of London, and Ms. Leena Mitford of the British Library for their kind guidance.

1James Long, Returns Relating to the Publications in the Bengali Language in I857 (Calcutta, 1859) pp. xxiv-xxv

2Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996); Deana Heath, Purifying Empire: Obscenity and the Politics of Moral Regulation in Britain, India and Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

3The British left India in 1947, marking the successful culmination of half-a-century long freedom struggle that swayed between peaceful marches and spells of armed resistance punctuated with gunfire and bomb blasts. Independence came at a price, though, as the partition of Bengal and Punjab resulted in the greatest human migration in history. This period also witnessed communal riots in various parts of India, especially in Bengal and Punjab, claiming the lives of thousands of people. During the final stages of the Second World War, when the British government was apprehensive of a Japanese invasion from Axis-occupied Burma, they implemented a scorched-earth policy in Bengal Province. This resulted in a massive famine, entirely man-made, that claimed the lives of at least 4 million people.