Voices from the Sylff Community

Apr 23, 2020

Resilience Spaces: Rethinking Protection to Address Protracted Urban Displacement

Using an SRA grant, Pablo Cortés Ferrández conducted participatory action research (PAR) in Altos de la Florida, an informal settlement for internally displaced persons in an urban area outside Bogota, Colombia. He is making a firsthand analysis of the humanitarian conditions in the settlement to uncover challenges and propose pathways to improve interventions through protection and resilience approaches.

* * *

Capacity building for urban IDPs (internally displaced persons) and host communities is emerging as a new way of working to confront the root causes of protracted displacement in unsafe, informal settlements in Colombia. Despite the challenges, these urban contexts provide an opportunity to advance the complementarity, connectedness, and localization of humanitarian and development aid.

View of Altos de Florida and Soacha on the outskirts of Bogota, the capital of Colombia.

“I was displaced by the paramilitary from Llanos Orientales to Chocó in 2005,” says Yomaira, who lives with her husband and three children in Altos de la Florida, an informal settlement in urban Soacha, just outside the Colombian capital of Bogota. “Three years later we fled to the urban areas of Buenaventura and then again in 2012 to Bogota due to increased violence. In 2014 we started to build a house on this hill because the cost of living in the city was too high.” Yomaira’s narrative reflects the experience of many families for whom armed conflict prompted just the first of many internal displacements: 5.8 million people remain displaced in Colombia as of the end of 2019.[1]

The Root Causes of Displacement

In Colombia, initial displacements due to armed conflict or generalized violence often results in displacements again to urban areas, where families seek protection and economic opportunities. An estimated 87% of the country’s IDPs come from rural areas, and they wind up in the only places that they can access due to their vulnerability: the informal settlements,[2] where more than half of the IDPs live.[3] Both authorities and humanitarian, development, and peace actors need to better understand these supposed urban refuges.

This article is based on a research project implemented from 2015 until 2018 in Altos de la Florida, including surveys of 211 households, 98 in-depth interviews, 3 social cartographies, and 3 focus group discussions.[4] Altos de la Florida is a neighborhood in Soacha, a municipality of approximately 1 million people, the largest of the cities surrounding Bogota. Over two-thirds of its population was living under the poverty line as of 2010.[5]

According to the city’s development plan, 48% of the municipality—378 neighborhoods—are deemed “illegal” by local authorities. The IDP population in the municipality stood at around 50,000 in July 2018. Since the outbreak of the economic and political crisis in neighboring Venezuela, at least 12,300 Venezuelans have joined the ranks of Soacha’s displaced people.

Altos de la Florida suffers from the common pattern of social and spatial segregation in a poverty area with low-quality housing, services, and infrastructure: 72.9% of households are in conditions of structural poverty. The neighborhood as an urban community, formed by 1,011 families of around 3,657 people, has two main characteristics: 52.49% are less than 25 years old, and 48.81% are women.

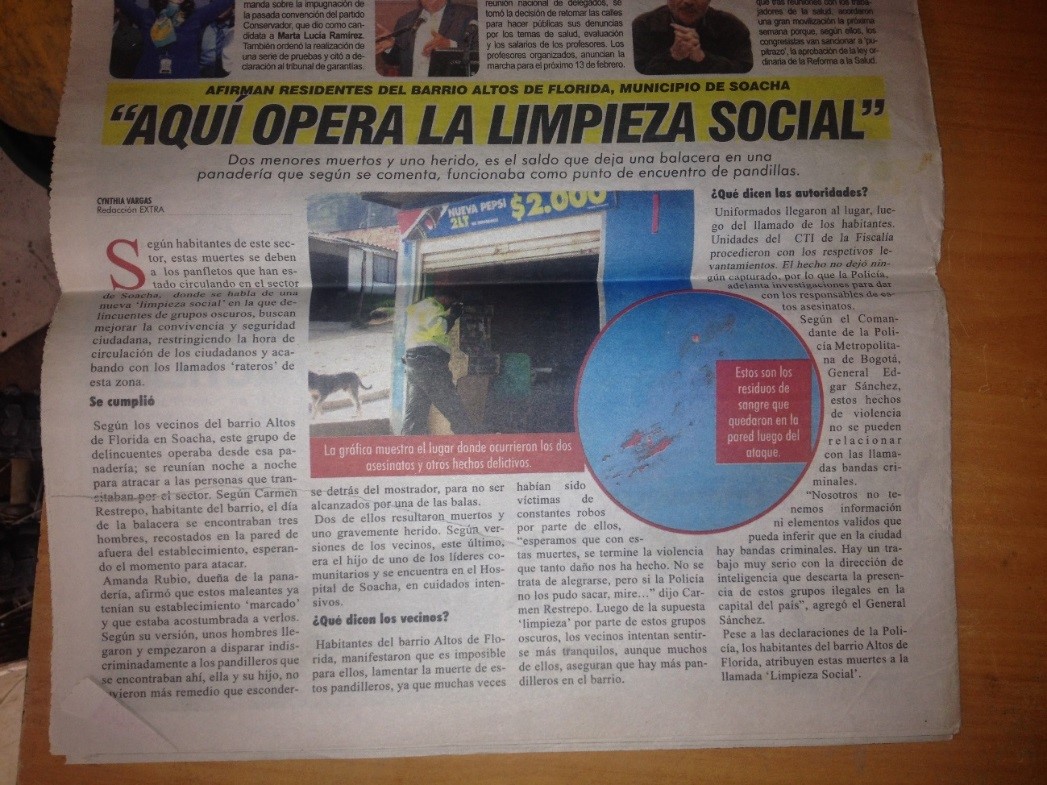

An article in a local daily linked so-called social cleansing with the murder of the son of a community leader in Altos de la Florida.

From One Informal Settlement to Another

The UNHCR and UNDP have diagnosed Altos de la Florida as a “vulnerable community due to the informality of the neighborhood.”[6] The informal nature of these urban settings limits the capacity to reduce vulnerabilities, yet the planning secretary of the mayor’s office refuses legalization.

Due to the absence of political will, households lack tenure security and have no official proof of home ownership. The neighborhood faced eviction attempts in 2009, and the lack of basic services and infrastructure in Altos de la Florida increases residents’ vulnerability. According to my survey results, 97.1% of households do not have access to drinking water except for a tank trunk, around 300 children need a kindergarten, and there are no primary health centers in the area—in fact, Soacha’s hospital has only 250 beds for 1 million people.

Altos de la Florida is regarded as an urban territory without state.[7] Urban violence increases protection risks. Informality combined with the settlement’s geostrategic position, and the absence of local authorities makes the neighborhood a strategic location for nonstate armed actors. According to Forensis data, the homicide index in Soacha was 40.58 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2016, the highest in the department of Cundinamarca. The profile of victims follows a common pattern seen in other urban contexts in Latin America: 91.5% are men, and 44.3% are between 20 and 29 years old. Interpersonal violence also represents a significant challenge with 2,898 cases per year, the fourth highest behind the cities of Medellin, Cali, and Barranquilla.

The lack of political will, the structural vulnerabilities of communities in informal urban areas, and high levels of insecurity are the causes of new urban displacements, both intra- and inter-urban. Re-victimization and re-displacement are the two main characteristics of this vicious cycle. Intra-urban displacement is the victimizing event with the greatest impact on the urban dynamics of the conflict in Colombia.[8] Urban IDPs are forced to flee their informal settlements due to violence, only to arrive in other settlements with similar protection risks. Informal settlements are therefore at once expelling zones and arrival areas for displaced populations. In socially and spatially segregated Altos de la Florida, IDPs represent 30%–40% of the population.

A man in Altos de la Florida building a brick house.

Promoting Community Participation

Humanitarian, development, and peace actors have increased their interest in urban contexts in recent years. Despite increasing knowledge, though, a lack of experience and challenges inherent to urban settings continue to undermine humanitarian and development interventions. International humanitarian aid began in 2001, when World Vision International established a presence in Colombia. In 2006 UN agencies and the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) started their intervention. Particularly interesting was the UN Human Security Program (2010–12) and the UN Transitional Solutions Initiative (TSI) project (2012–16).

In the settlements, a protracted and supply-driven emergency response has caused people to become dependent on external aid. Emergency assistance is an essential form of humanitarian aid, mainly for displaced families, but protracted aid can discourage community participation and increase the gap between assistance and development. According to one development worker operating in the neighborhood, to avoid creating dependency, “it is necessary to promote sustainable public policy solutions and the participation of IDPs in the political, economic, and social life of the host community.”[9]

The dependency of community leaders on humanitarian assistance also undermines social cohesion in the neighborhood. Limited consultation and lack of coordination decreases the effectiveness of the intervention. Past project evaluations have found that “international cooperation is insufficient and requires the integral intervention of the State.”[10] Therefore, achieving a durable solution for urban displacement requires closer collaboration between the humanitarian sector and local authorities, along with strong political will at both the local and national levels.

Resilience Spaces as a Protective Approach

In urban informal settlements, humanitarian, development, and peace actors must work in a weakened and less cohesive social engagement environment, exacerbated by sporadic violence. These circumstances lend themselves to short-term responses and silo-approaches to deal with emergencies, further increasing dependence among the communities that receive support. Poorly integrated responses have limited capacity to address complex urban crises. Cooperation between humanitarian and development actors and engagement with national and local actors are essential, given the potentially limited capacity and political will of certain municipalities.

The protracted vulnerability of urban IDPs and host communities in informal urban contexts has revealed the need for real change in humanitarian aid, particularly as fragile situations are exacerbated by urban violence. Protracted urban displacement requires better connectivity between humanitarian and development efforts, and the needs of IDPs should be balanced with those of the host communities. Current debates show a growing consensus around new and comprehensive approaches. To face the challenges of protracted urban displacement, interventions must go beyond immediate humanitarian needs and should aim to reduce the vulnerabilities of both IDPs and local host communities.

Humanitarian aid should be committed to not only ensuring survival but also supporting people to live in dignity. “Resilience spaces” were developed as a complementarity approach in the UNHCR’s Policy on Refugee Protection and Solutions in Urban Areas (2009), combining assistance and recovery by not only addressing urgent needs but also strengthening local capacities. The framework combines a top-down protection approach with a bottom-up capacity building approach through three areas of intervention: creating education, economic, and labor opportunities; strengthening social cohesion; and, supporting leadership capacities.

Such resilience spaces have been set up in Altos de la Florida, resulting in the creation of two important grassroots organizations in the informal settlement: Comité de Impulso, a fortnightly meeting among community leaders, dwellers, IDP associations, and humanitarians; and Florida Juvenil, a youth community organization engaged in break-dance, theater, and football activities.

Resilience has emerged as one of the strongest responses to the humanitarian and development divide. In Altos de la Florida, the joint work of humanitarian and development actors, in collaboration with national and local counterparts, aims to achieve collective results in the short to medium term (three to five years) to reduce risk and vulnerability. The situation in Altos de la Florida features three criteria that are on the rise in modern humanitarianism and deemed essential in urban responses to displacement: complementarity, connectivity, and sustainability.

A youth theater group supported by Fe y Alegría in Altos de Florida.

In Altos de la Florida, international actors strengthened rather than replaced local and national systems. The complementariness of response included collaboration with local and national aid providers in affected territories, empowerment of leaders of both local and national NGOs and community-based organizations, as well as inclusion of authorities and municipalities at the urban level. Going beyond complementarity, connectivity can not only to bridge the humanitarian-development divide but also incorporate approaches like resilience, which is key to strengthening local capacities. Sustainability, evident through positive long-term results for the supported individuals and societies, depends directly on this capacity for collaboration among the actors and the strengthening of local and national capacities.

Currently, there is consensus in the humanitarian community that in urban contexts populations can be protected by strengthening their capacity. In this sense, humanitarian action has a particular and perhaps unique role in protecting the population through strategies that allow people to build their resilience. Resilience approaches bridge lingering disparities and disconnections between humanitarian and development responses in urban interventions. The approach observed in Altos de la Florida helps better articulate an urban response around the construction of resilience as an instrument of protection. This protection, in turn, represents a comprehensive strategy to address the root causes of urban displacement.

Resilience space in Altos de la Florida supported by the Jesuit Refugee Service.

[1] IDMC (2019), ‘Global Report on Internal Displacement 2019’, IDMC, p. 44, https://bit.ly/2WNKeKQ.

[2] CNMH (2010), ‘Una nación desplazada. Informe nacional del desplazamiento forzado en Colombia,’ CNMH and UARIV, p. 38, https://bit.ly/29uyNzv.

[3] IDMC (2015), ‘Global Overview 2015. People internally displaced by conflict and violence,’ IDMC, p. 20, https://bit.ly/2TSq3ZK.

[4] This part of the project was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 691060.

[5] UNDP (2010), ‘Política Pública de Desarrollo Social Incluyente. Municipio de Soacha,’ UNDP.

[6] UNHCR and UNDP (2017), ‘Documentación proceso de integración local comunidad Altos de la Florida, Soacha,’ UNHCR and UNDP, https://bit.ly/2SQ0vgc.

[7] Laura Tedesco (2007), ‘El Estado en América Latina ¿fallido o en proceso de formación?’ Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior, Vol 37.

[8] CODHES (2013), ‘Desplazamiento forzado intraurbano y soluciones duraderas,’ CODHES, p. 18, https://bit.ly/2EEfmpf.

[9] Interview, April 4, 2016, with a UNDP TSI coordinator in Soacha.

[10] Econometría Consultores (2016), ‘Evaluación externa del programa “Construyendo Soluciones Sostenibles-TSI,”’ Econometría S.A., p. 19.