Voices from the Sylff Community

Nov 10, 2016

Verbs and the History of Bantu Languages Near the Serengeti

It is said that there are more than 6,000 languages spoken today in the world. The majority of them are so-called minority languages and are endangered. Timothy Roth, a 2014 Sylff fellow of the University of Helsinki, conducted fieldwork in Tanzania to examine four Mara Bantu languages—so-called minority languages—using an SRA award. His article, explaining the findings from his fieldwork, highlights the importance of “minority” languages.

***

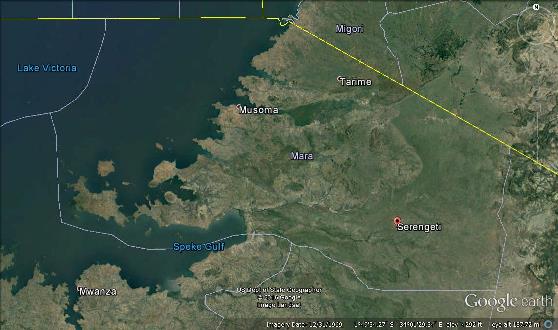

The Mara Region of Tanzania is home to over 20 different language varieties in an area the size of the US state of Delaware.ⅰMara is situated between Lake Victoria to the west and Serengeti National Park to the east, with the nation of Kenya just to the north. As one might assume, the sheer density of languages and dialects in the region is quite remarkable. Although there are several Nilotic languages in the region, most of the varieties belong to the Bantu language family.

The area around Lake Victoria is extremely important for reconstructing the history of the Bantu peoples, specifically concerning the general routes taken across sub-Saharan Africa during what is called the “Bantu migration.” There is consensus among scholars that the Bantu migration took place several thousand years ago from what is now Cameroon.ii What is in dispute among historians (and researchers from other disciplines) is the direction(s) in which the early Bantu communities moved. One major hypothesis places early Bantu communities to the west of Lake Victoria as the result of a primary migration from Cameroon. Some of these early Bantu communities would have soon spread to the east side of the lake. This hypothesis happens to correspond well with the paleoecological and archaeological evidence.iii

Many of the languages in Mara are endangered to varying degrees and are linguistically underdescribed. There are many language endangerment issues here in terms of the need for language documentation, legitimacy, and the dynamic effects that language development and mother-tongue education can have on the communities themselves. There is an innate value to minority languages whereby language and cultural preservation result in a “mental” or “intellectual” wealth that belongs to humanity.iv

Hale says, “At this point in the history of linguistics, at least, each language offering testimony for linguistic theory brings something important, and heretofore not known or not yet integrated into the theory. In many cases, data from a ‘new’ language forces changes in the developing theory, and in some cases, linguistic diversity sets an entirely new agenda.”v

Thus, any additional linguistic understanding of the Mara languages could have ramifications not only for Bantu migration hypotheses but also for the advancement of current linguistic theory.

My research concerns four of these Mara Bantu languages: Ikoma, Nata, Isenye, and Ngoreme. These languages are closely related and form a subgroup called Western Serengeti. I am working on multiple languages rather than just one because the density of Bantu languages in the Mara region provides a unique opportunity to compare closely related languages. My research is focused on verbs, specifically the grammatical markers that encode tense, aspect, modality, and evidentiality (TAME). In Bantu languages—and many other languages around the world—differences in pitch can change the meaning of words and can also apply to these grammatical TAME markers; this concept is called “grammatical tone” and is a crucial part of any analysis of the verbal system. I am comparing the function and meaning of the TAME markers in Western Serengeti in order to understand how they developed and what that reveals about the history of these languages. As far as methodology is concerned, a focus on function and meaning (and not just forms) makes it necessary to combine any elicitation with the collection of natural texts.

For the first phase of my research, I went to Musoma, Tanzania, in October 2014 as a Sylff fellow and collected initial data from each of the languages. This initial data mostly consisted of elicitation from lists of words and sentences but also included audio recordings of stories and conversations. Because the TAME systems were underdescribed, I needed to cast a wide net to see what I would find. (Bantu languages are known for having intricate TAME systems.vi) The first phase was certainly a success, as I was able to figure out the general pattern of how the present-day TAME systems are organized. Surprisingly, I found that the systems are organized primarily around aspect (perfective versus imperfective) and not tense. This type of organization is more like some of the non-Bantu Niger-Congo languages of West Africa.vii

These surprising facets of the initial research made the second phase that much more important, as I had many remaining questions as a result. For example:

• If the systems are organized around aspect, how do speakers choose a particular aspect to communicate past, present, or future? Is it merely whether the event is viewed as complete or incomplete?

• Do the semantics of the verbs themselves (lexical aspect) influence the selection of certain grammatical aspects? Are there any restrictions on which verbs can take which grammatical aspects?

• Quite a bit of overlap exists in some of the aspects that cover (what would be) the immediate past and present. Does modality play any role in distinguishing between these?

With the SRA grant, I traveled again to Tanzania in June 2016 for the second phase of fieldwork. I worked on my research for two weeks at the SIL International Uganda-Tanzania Branch regional headquarters in Musoma. I brought in two mother-tongue speakers per language group as language informants for two to four days each and used Swahili to talk with them about their language(s) and conduct the research. Part of the research included transcription of previous audio data as well as word-for-word translation into Swahili. Additional research elements included further elicitation and recording (for lexical aspect and grammatical tone).

With the research that the SRA grant allowed me to undertake, not only did I gain some answers regarding the first two questions above, but the major finding came in relation to the third question: in three of the languages—Ikoma, Nata, and Isenye—the morpheme -Vká- combines inceptive aspect with what is called witness/non-witness evidentiality. Although not modality per se as initially expected, evidentiality is the “grammatical marking of information source.”viii In Ikoma, Nata, and Isenye the inceptive is used if the report comes from a witness to the event, while the perfective is used if the report comes from a non-witness to the event. Evidentiality has not been described for many African languages and is definitely an emerging area for research.

In addition, evidentiality has a clear relationship with episodic memory, or “the memory of past events that have been personally experienced and is thus based on sensory information.”ix

Tense and aspect also have clear relationships with storytelling and, more generally, how events are conceptualized by speakers. Using the cognitive linguistic concept of construal, for instance, tense and aspect can be explored in terms of how speakers perceive themselves and time in relation to events. The construals “ᴛɪᴍᴇ is a ᴘᴀᴛʜ” and “ᴛɪᴍᴇ is a sᴛʀᴇᴀᴍ” form the backbone for these relationships. In a ᴘᴀᴛʜ construal, the speaker views himself as moving while time remains unmoving. In a sᴛʀᴇᴀᴍ construal, however, time is moving and either the speaker or the event are seen as moving along with it.x

Remember that the systems in the Western Serengeti varieties are organized primarily around aspect without nearly as many tense distinctions as other Bantu languages. Aspect “denotes a particular temporal phase of the narrated event as the focal frame for viewing the event.”xi Think of different aspects in this sense as different video cameras set up around an event with one capturing the beginning, one the end, one the whole thing, and so forth. In Ngoreme, for example, there are at least four ways of communicating the “present tense” as shown immediately below. The underlined portions of the italicized Ngoreme verbs are the parts of the words that make their meanings different.

Ngoreme (Roth fieldnotes 2014, 2016)

a. Progressive

nkohíka bhaaní

b. Perfective

mbahíkire c. Imperfective

mbarahíka

d. Inceptive

bhaakáhika

“They [the tourists] (arrive, are arriving) [at the top of the mountain].”

If we begin to think about aspect in relation to the many verb forms involved in constructing a narrative, we can see how there are a multitude of choices available for the speakers of these languages to frame the story, and the events within that story. In analyzing narrative discourse, there is some scaffolding available to the speaker with some aspects used for foreground material (sequence of events) and others for background (e.g., flashbacks).xii But in Western Serengeti these choices can also be affected by formal versus informal register considerations (e.g., Biblical text versus a folktale or story told over lunch).xiii In Storytelling and the Sciences of Mind, Herman says that there is an “inextricable interconnection between narrating and perspective taking” and, further, that “storytelling acts are grounded in the perceptual-conceptual abilities of embodied human minds.”xiv Why then do speakers make the choices they do, and what does that tell us about the human mind and cognition? I hope that my research may help to widen our understanding of what is possible in terms of cognition and memory, storytelling, and the conceptualization of events.

Not only does my research play a role in these types of questions, but it also has implications across several academic disciplines in addition to linguistics (e.g., history, sociology, and archaeology). Specifically, I hope my investigation will, in coming from a linguistic perspective, build on the research of Jan Bender Shetler who has written two integral sociohistorical works on the ethnic groups in Mara, Telling Our Own Stories and Imagining Serengeti. The former is mostly a collection and analysis of oral histories from several ethnic groups in Mara, including origin stories. The latter focuses on spaces and landscape memory and draws on multidisciplinary evidence (including archaeology) to support the argument that the Western Serengeti peoples have deep historical roots in the Serengeti land itself. Comparative tense/aspect research here should shed further light on where these groups originally came from, how they are related to one another and to other Bantu languages in Tanzania, historical movements, and possible contact with Nilotic and Cushitic peoples. Like fingerprints, the somewhat unique set of similarities and differences in the tense/aspect paradigms may in this way allow for an advancement in our understanding of the sociohistory of these ethnic groups.

Finally, as I mentioned briefly above, my research also has a part to play regarding the innate value of minority languages. Even though minority languages in Tanzania are often treated as lesser, by doing linguistic research in these languages we are able to treat what is inherently valuable as worthy of study and with proper respect. My research and subsequent dissertation allow for additional features of these languages to not only be documented but also be shared with the academic community worldwide. This material includes recorded stories and conversations, transcriptions of those recordings, and their Swahili and English translations. This fits right in with the ethos of the Helsinki Area and Language Studies (HALS) initiative at the University of Helsinki, not to mention the language development work that SIL is doing in the area: developing orthographies, providing literacy programs, translation, and increasing language vitality in the process.

iHill, Dustin, Anna-Lena Lindfors, Louise Nagler, Mark Woodward, and Richard Yalonde. 2007. A sociolinguistic survey of the Bantu languages in Mara Region, Tanzania. Unpublished ms. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: SIL.

iiPakendorf, B., K. Bostoen, and C. de Filippo. 2011. Molecular perspectives on the Bantu expansion: A synthesis. Language Dynamics and Change 1: pp. 50–88.

iiiNurse, Derek. 1999. Towards a Historical Classification of East African Bantu Languages.”In Hombert, Jean-Marie and Larry M. Hyman (eds.), Bantu Historical Linguistics: Theoretical and Empirical Perspectives, pp. 1–41. Stanford: CSLI. p. 9.

iv Hale, Ken. 1998. “On endangered languages and the importance of linguistic diversity.” In Grenoble, Lenore A. and Lindsay J. Whaley (eds.), Endangered languages: Current issues and future prospects, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 193.

vIbid. p. 194.

vi Botne, Robert and Tiffany L. Kershner. 2008. Tense and aspect in cognitive space: On the organization of tense/aspect systems in Bantu languages and beyond. Cognitive Linguistics 19 (2): pp. 145–218. p. 146. The E is left out here because African languages are not known for having evidentiality (see Aikhenvald 2004: p. 291).

vii Nurse, Derek. 2008. Tense and aspect in Bantu. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 281.

viii Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2004. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 392.

ixDahl, Ӧsten. 2011. The structure of human memory and tense-aspect-mood-evidentiality (TAME). Abstract. Website: http://www.mpi.nl/events/mpi-colloquium-series/mpi-colloquium-series-2011/osten-dahl-february-15

xBotne and Kershner 2008: pp. 147–50.

xiIbid. p. 171.

xiiNicolle, Steve. 2015. Comparative Study of Eastern Bantu Narrative Texts. SIL Electronic Working Papers 2015_003. Website: http://www.sil.org/resources/publications/entry/61479. pp. 36ff.

xiiiIbid. p. 45.

xiv Herman, David. 2013. Storytelling and the Sciences of Mind. Cambridge: The MIT Press. p. 169.