Voices from the Sylff Community

Nov 14, 2012

Japanese Language Education at Chinese Universities

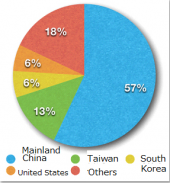

Of the approximately 3.65 million students of the Japanese language outside Japan, the highest numbers are in South Korea (960,000) and China (830,000). China, though, claims more students at the tertiary level, at 530,000. How are Chinese university students learning the Japanese language and gaining an understanding of the country’s culture?

Yusuke Tanaka, a 2009 recipient of a Sylff fellowship as a student at the Waseda University Graduate School of Japanese Applied Linguistics and a research fellow at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, conducted a detailed study and analysis of Japanese language education at Chinese universities. He examined textbooks and curricula and interviewed both teachers and students. His research revealed features quite distinct from those seen in South Korea and Taiwan.

The following are excerpts from his report:

Of the 1,170 universities in China, there are 466 that offer majors in the Japanese language. The figure is a threefold jump from 1999, when the Chinese government introduced a policy to expand the number of university students in the country.

The aim of this report is to examine how students of the Japanese language at Chinese institutions of higher learning—which today enjoy a growing global presence—are learning the language. Specifically, the analysis focuses on classes in jingdu (Comprehensive Japanese), the chief course taken by Japanese majors at universities in Beijing, Shanghai, and Dalian, examining and analyzing the Japanese text found in course textbooks.

The examination revealed three major characteristics. (1) The jingdu textbooks widely used today frequently quote the same passages and authors as those appearing in kokugo (Japanese language) textbooks used at schools in Japan. An extremely high percentage of Chinese students are thus exposed to the same materials as Japanese schoolchildren. (2) When creating Japanese language textbooks in China, kokugo textbooks are considered one of most reliable sources for quoting passages. (3) Inasmuch as teachers, students, textbook publishers, and researchers, as well as the instruction guidelines all concur that the aim of Japanese language instruction is be to gain an “accurate understanding of the Japanese language, Japanese culture, and the Japanese mind,” many believe it is only natural and logical for materials appearing in Japanese high school kokugo textbooks to overlap with textbooks for Chinese learners of the Japanese language.

The study revealed that the teaching materials and methods used in Japan had a definite influence on the way Japanese was taught to Chinese university students, suggesting that domestic teaching methods have a role in Japanese language education abroad. Both learners and instructors pointed to biases and deficiencies in Japanese textbooks, however; one researcher noted that the grammatical system adopted in the textbooks was designed for native speakers of Japanese, making it unsuitable for Chinese students of the language. Others voiced the need to make a clear distinction between native and foreign learners, adjusting the content and methods of Japanese language instruction accordingly to meet fundamentally contrasting needs and aims.

There was also a perceived need to be vigilant for normative elements and assumptions about universality that, by nature, are part of language instruction for native speakers. And there may be a danger in referencing textbooks that are designed for domestic use and contain—as some claim—biased content as sources for the “accurate understanding of the Japanese language, Japanese culture, and the Japanese mind.”

Nevertheless, making a mechanical distinction between Japanese language instruction for native and foreign speakers and simplistically assuming them to be isolated concerns will only hinder efforts to gain a true grasp of Japanese language teaching in China. Rather, there is a need to broaden our perspective and fully acknowledge the intertwining of the two approaches to language teaching that now exist in China. This, I believe, is an extremely important consideration in understanding the diverse and fluid nature of foreign languages and cultures and in reexamining what Japanese language education in China should seek to achieve and how it should be structured. I thus hope to conduct further research and analysis into this topic.

This study focused on an analysis of textbooks used in Japanese language instruction at Chinese universities. I would be most happy if the findings of this report—that the methods used to teach Japanese to native speakers deeply influence how the language is learned by nonnatives—would become more broadly known to Japanese language educators both in Japan and other countries.

Read the full Japanese report at: www.tkfd.or.jp/fellowship/program/news.php?id=130