The growing demand for high-quality survey data and the shrinking supply of qualified interviewers are creating a bottleneck that threatens the reliability, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability of survey operations, caution Blanka Szeitl (Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2023) and co-authors Gergely Horzsa and Anna Kovács.

Gap between Standardization and Practice

In Hungary, large numbers of surveys are conducted each year. The Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH) alone collects around 1.2 million questionnaires annually (KSH 2021), and when market and political polls are included, the total likely exceeds 3 million (Szeitl 2024). This magnitude highlights the importance of survey research and the need to examine its quality. This study focuses on a specific aspect of survey quality: the effect of those collecting the responses, that is, the interviewers.

Survey research is built on the idea that interviews can be standardized so that all respondents are asked the same questions under the same conditions, producing data that reflect real attitudes rather than interaction effects. For decades, this has been treated as a gold standard in survey methodology. Methodological literature emphasizes scripted wording, neutral tone, consistent behavior, and minimal deviation from protocol as key factors in reducing error (Cannell and Kahn 1968; Groves et al. 2009).

However, research has also shown that interviews are inherently social interactions in which meaning is co-constructed by interviewer and respondent. More recent papers recognize interviewers as social actors whose behavior is shaped by training, labor conditions, organizational environments, and the challenges of obtaining cooperation in an era of declining trust (West and Olson 2017).

Despite this, most empirical work on interviewer effects remains quantitative, focusing on measurable outcomes such as nonresponse patterns, response distributions, or measurement error, while qualitative insights into how interviewers understand their roles and manage difficulties remain limited. Interviewers work in complex social environments, deal with distrust and emotional strain, and respond to organizational pressures that rigid standardization cannot fully anticipate. Therefore, deviations from standardization may not exclusively be “errors” but also strategies that make data collection possible.

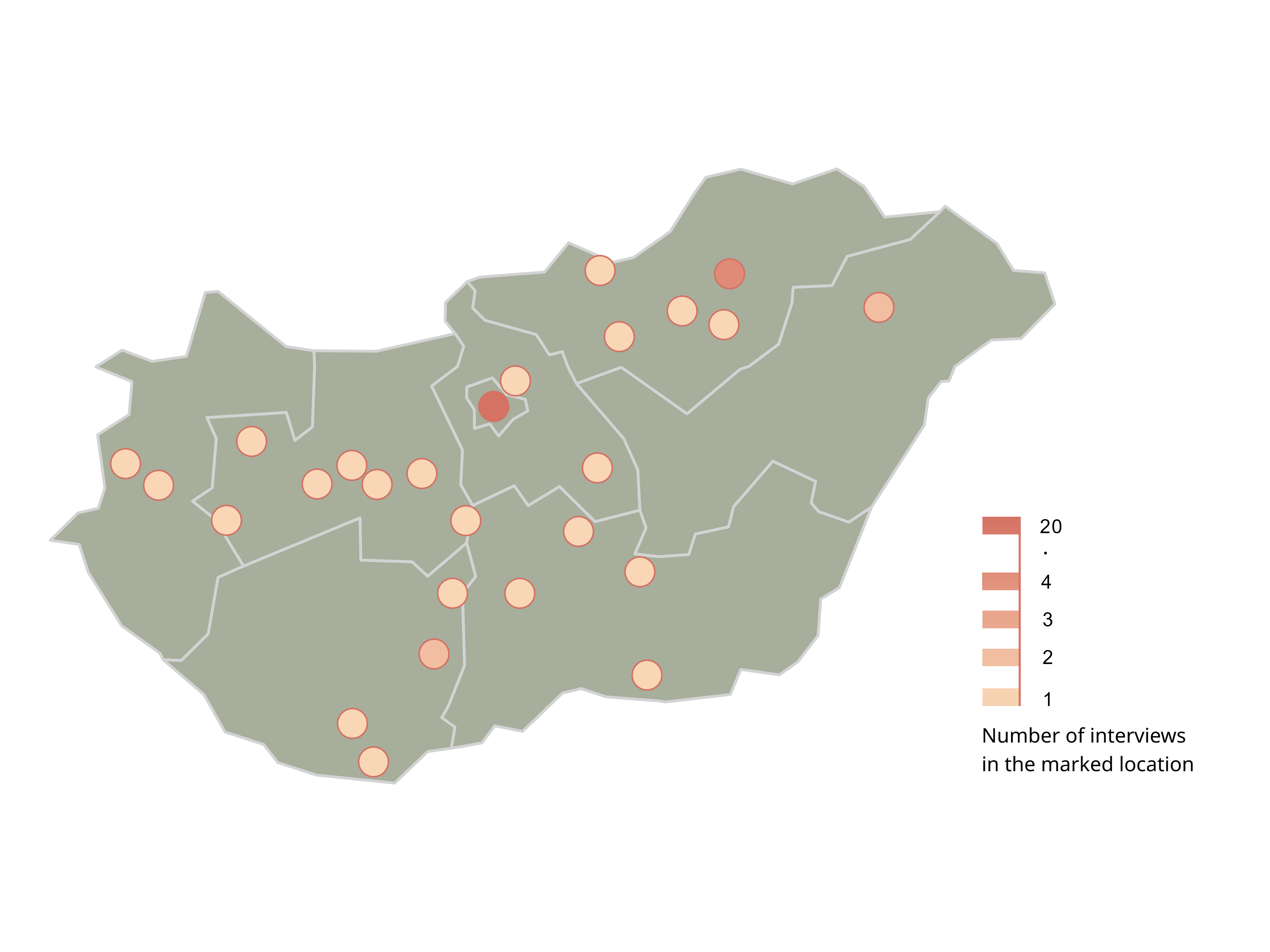

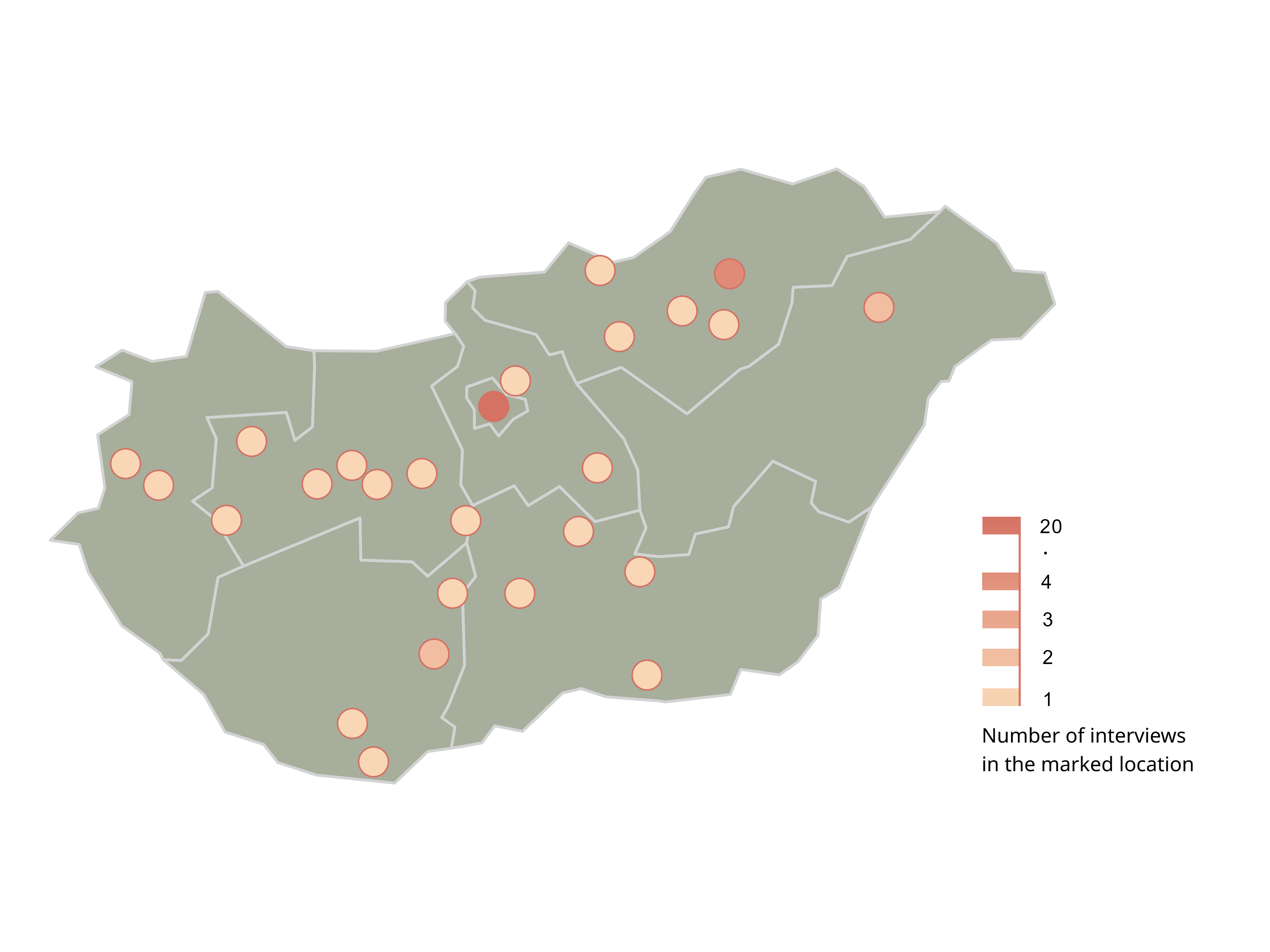

Based on 50 semi-structured interviews with survey interviewers and fieldwork instructors in Hungary (Figure 1), my SRG study explored these dynamics from the perspective of the interviewers who directly shape the interaction between research and the public. Rather than judging interviewers against methodological ideals, the research focused on how they conduct interviews and how their adaptations affect data quality.

Figure 1. Interview Locations during the SRG Study

Source: Created by the authors.

Interviewers in a Shifting Labor Environment

Most interviewers entered the field because it offered autonomy, flexible hours, and supplementary income.

By then, the child was already getting quite big, and I had less to do. And my husband is extremely independent, so I didn’t have to look after him. I had time, and sewing, handicrafts, and things like that didn’t tie me down. That’s how I got into it. [survey interviewer]

Very few younger people enter the field today, with interviewers describing the profession as one that “only older people do now.” Some attribute this to generational differences in motivation, while others point to the declining appeal and worsening conditions of fieldwork.

An image of an older female interviewer collecting data for a survey. Source: Freepik.

Most interviewers work on freelance or zero-base-rate contracts, receiving payment only after projects are completed and approved by clients. Several recalled waiting three to nine months for payment, with no formal guarantee of compensation. Payment for this work has also fallen markedly since the 1980s.

So we left him the radio log in paper form, whether he wrote down what he listened to on the radio correctly or incorrectly, we went, collected it, and in 1985 we got 100 forints for it. Then I went . . . and bought some cakes for the family, took them home, and we happily stuffed ourselves with income from one radio log, right? Today, people get 1,200 forints [3 euros] or 1,500 forints [4 euros] for one questionnaire, which is in fact the price of just a slice of cake, right? I’m just saying that if we compare it that way. [survey interviewer]

Interviewers also reported unpredictable workloads. Assignments arrive with little notice, deadlines are tight, and the amount of work varies from month to month. At the same time, the broader survey environment has become characterized by low trust. Respondents, increasingly skeptical of unknown organizations and wary of sharing personal information, are more likely to refuse participation. Interviewers also perceive a growing mistrust from research organizations and clients, expressed through GPS tracking, audio monitoring, and detailed scrutiny of their behavior. These forms of surveillance were described not only as stressful but as a sign that interviewers are assumed to be untrustworthy until proven otherwise.

Yet, interviewers are expected to perform complex emotional labor, like managing rejection, navigating suspicion, calming anxious respondents, and persisting in the face of hostility or indifference. This emotional labor remains largely unrecognized and unsupported within research organizations.

Many people [new survey interviewers] ran away from me screaming because they said it was a job that would destroy your nerves, your soul, everything. [survey field instructor]

Interviewers also face numerous practical obstacles. Sampling files frequently contain outdated or incorrect addresses, forcing interviewers to spend hours searching for households that no longer exist or have long since moved. Poorly designed questionnaires—lengthy, repetitive, or written in unclear language—exacerbate the frustration of respondents.

You leave in the morning, and you don’t know what you’re going to do, whether you’ll need ten days, or one, or two. [survey interviewer]

These structural issues place interviewers under constant time pressure, pushing them to find ways to navigate the demands of fieldwork while still producing usable data. The interviews reveal that this navigation often involves informal practices that deviate from strict standardization.

Adaptive Strategies for Securing Cooperation

Interviewers routinely adjust, soften, or reinterpret standardized procedures to build rapport, sustain cooperation, and complete their assignments. One major theme is the restoration of the human element of the interaction. Interviewers emphasize patience, empathy, and interpersonal warmth as essential tools for overcoming suspicion. Many describe the early moments of contact as a kind of emotional negotiation. Through small gestures of understanding, they work to shift the interaction from a defensive posture to one of openness.

An image of a survey respondent by the gate of his house. Source: Freepik.

Another strategy involves making selective decisions about where and when to conduct interviews. Interviewers often avoid neighborhoods they perceive as hostile or unsafe, instead prioritizing areas where they expect cooperation to be higher. While these choices improve efficiency, they also carry implications for sample representativeness.

Interviewers also describe numerous ways of managing questionnaire length. Some shorten interviews by summarizing or selectively skipping redundant or confusing items. Others take quick notes during the interaction and complete data entry of the full answers later at home. These adjustments enable interviews to proceed in a reasonable time frame, particularly with tired or hesitant respondents.

Personalization is also widespread. Interviewers frequently rephrase questions, offer clarifications, or gently guide respondents toward appropriate categories when questions are complex. Far from seeing these practices as violations of protocol, interviewers view them as essential for respondent cooperation.

Implications for Survey Research

Taken together, these findings reveal a fundamental tension between the ideal of standardized interviewing and the realities of fieldwork. Deviations are not random errors but practical responses to time pressure, mistrust, and limited organizational support. Some strategies improve respondent understanding and reduce refusals, while others risk introducing bias. Shifting the focus from standardizing interactions to standardizing outputs, such as coding, documentation, and reporting of deviations, could help preserve data quality while allowing interviewers the flexibility needed in the field. Achieving this requires investment in training, fair compensation, and supportive organizational structures.

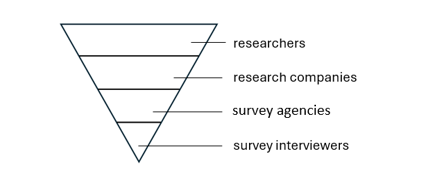

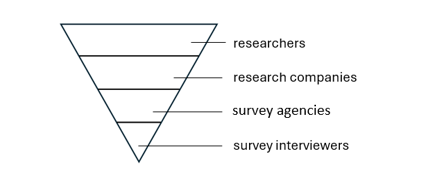

The current landscape of survey data collection can be conceptualized as an inverted pyramid (Figure 2), reflecting the increasing structural imbalance within the field. At the top are the researchers, representing a relatively large and growing group of professionals who design studies, interpret data, and set methodological standards. Below them are the research companies, whose role is to manage projects, coordinate fieldwork, and ensure quality control. Further down are the survey agencies, which are responsible for the operational aspects like recruitment, scheduling, and supervision of interviewers.

At the very bottom of the inverted pyramid are the survey interviewers: the group that is, paradoxically, both the smallest in number and the most crucial for the execution of survey research. Despite being the backbone of high-quality empirical data collection, their availability has been declining rapidly. This shrinking base creates a structural vulnerability: the entire system depends on a diminishing pool of fieldworkers, whose work conditions, motivation, and professional support have deteriorated in recent years. The imbalance between the expanding demand for high-quality data and the contracting supply of qualified interviewers results in a bottleneck that threatens the reliability, cost-effectiveness, and timeliness of survey operations.

Figure 2. Survey Research Pyramid

Source: Created by the authors.

The inverted pyramid thus illustrates a systemic tension: while academic and commercial expectations toward survey quality and methodological rigor continue to rise, the human infrastructure required to deliver these standards is weakening. This structural mismatch poses one of the most significant contemporary challenges for the sustainability of survey research.

The results of this study are presented in detail in two manuscripts. One focuses on the local history, formation, and development of the interviewer network (in Hungarian; current version available here), while the other examines how the factors influencing survey quality can be grouped (current version available here).

Blanka Szeitl, far right, with members of her research group.

Read about the research group

Read more about the interview details

References

Cannell, Charles F., and Robert L. Kahn. 1968. “Interviewing.” In The Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by Gardner Lindzey and Elliot Aronson, 526–95. Vol. 2. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Groves, Robert M., Floyd J. Fowler, Mick P. Couper, James M. Lepkowski, Eleanor Singer, and Roger Tourangeau. 2009. Survey Methodology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH). 2021. Activities of the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 2020–2021. Technical report. Budapest: Hungarian Central Statistical Office.

Szeitl, Blanka. 2024. Surveying the Human Population: Errors and Their Corrections. PhD diss., University of Szeged.

West, Brady T., and Kristen Olson. 2017. “Interviewer Effects in Survey Data.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Survey Research, edited by David L. Vannette and Jon A. Krosnick, 329–47. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

“I’m very excited to finally be here,” Sakata said of her first visit—not only to the Sylff office

“I’m very excited to finally be here,” Sakata said of her first visit—not only to the Sylff office Sakata expressed her hope of applying the lessons from her current trip to Japan to make a greater contribution to the Sylff community in São Paulo and beyond. The secretariat was heartened by her offer and looks forward to sharing her future engagements with the broader Sylff community. (Compiled by Nozomu Kawamoto)

Sakata expressed her hope of applying the lessons from her current trip to Japan to make a greater contribution to the Sylff community in São Paulo and beyond. The secretariat was heartened by her offer and looks forward to sharing her future engagements with the broader Sylff community. (Compiled by Nozomu Kawamoto)

As 2025 draws to a close, we extend our heartfelt gratitude to all members of the Sylff community for your continued commitment to the ideals and operations of our program.

As 2025 draws to a close, we extend our heartfelt gratitude to all members of the Sylff community for your continued commitment to the ideals and operations of our program.