In Puerto Rico, midwives used to be the primary care providers for expecting individuals and families. But the community-based model has been displaced by hospital-based care—an unsustainable model with less-than-optimal birth outcomes. Holly Horan, 2015–2016 Sylff fellow and doula, used a Sylff Leadership Initiative grant to work with community partners and convene leaders and practitioners to improve integrated perinatal care in Puerto Rico.

* * *

“My midwife saved me from a cesarean”, my doula client shared with me when reflecting on her first birth. “She saved me from being cut in half because the doctors don’t have faith in the process [of physiologic birth].”

It was a comfortable, late winter evening at my client’s home in the suburban sprawl of San Juan, Puerto Rico. I was conducting my dissertation research on maternal stress and timing of birth and undergoing pre-midwifery training at the community center Centro MAM (MAM) in Carolina. My pre-midwifery training required that I provide doula services for homebirth clients working with MAM’s midwife team. This was our first prenatal visit, where I met the mother at her home to begin to discuss her goals and plans for birth and postpartum. At our visits, I would also share information, resources, and provide additional supports to the family as needed to achieve these goals.

I looked down and touched the cool tile floor, common to homes in this tropical environment, and thought for a moment. Then I said: “I’m so glad she was there with you. How did you feel about transferring to a doctor to when your birth wasn’t going as planned?”

My client sat in silence for a moment, embracing her 8-month pregnant belly that was home to her second child. She looked at me intently and said, “I thank God we have access to doctors when we need them. But they don’t like midwives, they don’t like people who use midwives. Holly, the whole process is so violent.”

Maternal stress and birth outcomes

I am a clinical, biocultural, medical anthropologist who specializes in applied and community-engaged research. I am the daughter of a Puerto Rican woman who had three spontaneous preterm births that clinicians could not predict nor explain. When I began to explore the intersections of maternal stress and birth outcomes (such as timing of birth), I asked my mom why she thought she had preterm births. Her response was brief but complex: “I don’t know, but life was hard.”

Robust research has found associations between racism, chronic stress, and poor perinatal health outcomes. As I read the literature, I started to think about how my mom was the only person of color in our Midwest neighborhood. And I remember public instances of blatant discrimination that occurred in front of us, her children. This led me to a professional pursuit exploring experiences of maternal stress – to better understand from social and biological perspectives how such experiences manifest and to think about reducing stress through mechanisms that focus on respecting the lived experiences of the pregnant person.

At the same time I started my doctoral program in 2012, I trained as a birth and postpartum doula. I became familiar with models such as the JJ Way,[i] which has shown that a supportive, midwifery-led, person-centered model of care can nearly ameliorate preterm birth rates. When I told my mom I was becoming a doula, she responded: “A what?!” —a common reaction still despite rising awareness about doulas, globally.

Doulas are non-clinical providers who offer customized education, resources, and support during the perinatal period to meet the expecting family’s needs.[ii] When I explained to my mother what doulas do, she commented: “I can’t imagine what that could have done for me.” I also told her about the midwifery model of care, to which she said, “Why don’t women have more access to these wonderful things? Even if you need a doctor, they can work together.”

The coopting of community birth knowledge in Puerto Rico

My mother’s personal experience inspired me to better understand the lived experience of stress, the embodiment of stress, and preterm birth among pregnant people living in Puerto Rico. I came to intimately understand our perinatal healthcare system in the United States, as Puerto Rico is currently colonized as a US territory. I learned about the role of midwives in Puerto Rico in the early era of US colonization, where midwives served as community-based, public health professionals, primary care providers, and healers known as comodronas.[iii]

I learned about their integration into the public health and biomedical system and, ultimately, their near extinction that coincided with the growth of the biomedical industrial complex—a complex that co-opted the pregnancy, birth, and postpartum-care knowledge and procedures that midwives and others founded and openly shared with physicians to collaborate to better serve pregnant people across the United States and US territories. By the 1970s, comodronas in Puerto Rico, like midwives elsewhere in the United States, went underground because of the due to the elimination of regulation and licensure for their profession and as the healthcare system began to decentralize and privatize.[iv],[v],[vi],[vii]

Fast-forward to the 2000s and see the landscape of maternity care in the United States and US territories dramatically changed, and not entirely to the betterment for birthers and their families. Over four decades (1960s to 2000s), birth in Puerto Rico transitioned predominately to the hospital setting, where obstetricians practice care that is “technocratic, interventionist, and hierarchical.” Within this setting, obstetricians have increasingly conducted episiotomies cesareans, and restricted access to partners and family members.[viii] Today, obstetrician-attended birth is the norm on the island, and other providers, such as midwives, are still not recognized or regulated despite evidence-based research demonstrating the profound efficacy of the midwifery model of care across birth settings and geographic contexts.

Further, despite there being more than 500 trained obstetricians on the island, only one-fifth of them practice obstetrics, with the remainder offering only gynecological services. Unlike many obstetric and midwifery practices in the United States, where labor and delivery units and birth centers rotate on-call shifts for providers, many providers in Puerto Rico work in high-volume, single-provider practices.[ix]

This model of care is unsustainable and negatively impacts perinatal health outcomes. Currently, the island has significantly higher rates of primary (first birth) cesarean birth (42.2% in Puerto Rico versus 25.6% in the United States),[x] perinatal mortality (infant deaths between 28 weeks of pregnancy to 28 days after birth; 7.9/1000 in Puerto Rico versus 6/1000 in the United States),[xi] and preterm birth (an infant born <37 weeks of pregnancy; 11.6% in Puerto Rico versus 10.1% in the United States).[xii]

Bringing together leaders to promote integrated perinatal care in Puerto Rico

In ethnographic research that I conducted with my Puerto Rican colleagues, the participants identified two critical steps to ameliorate outcomes and improve healthcare service delivery, namely:[xiii]

- legally recognizing and supporting additional maternity care options, including midwives and doulas

- increasing patient and provider educational initiatives to convey the benefits of preventative medicine and “right-sized” maternity care

Based on the research, midwife instructor and Co-founder and Director of MAM Vanessa Caldari Melendez and I decided to develop a proposal for the Sylff Leadership Initiative. As a first step to work toward these potential solutions, we wanted to bring together perinatal care providers and professionals to re-imagine how we can encourage and implement collaborative perinatal care and perinatal health systems integration in Puerto Rico.

Collaborative perinatal care is when clinical and social support professionals work together to provide trauma-informed, patient-centered care to the expecting person and their family.

Perinatal health systems integration focuses on improving the healthcare infrastructure, such as by establishing standard operating procedures, allowing clinicians in the community setting to practice at the top of their scope, creating reasonable licensure policies for community providers, and expanding health insurance coverage and billing practices, to encourage collaborative perinatal care.

Community partners suggested hosting a conference to bring influential people within and Puerto Rico and from outside together to create a plan to improve perinatal healthcare on the island.

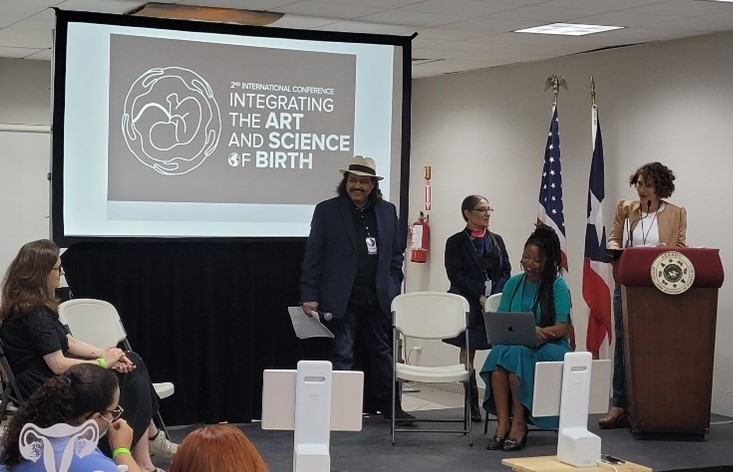

We submitted our proposal to Sylff in March 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. After months of delays, we hosted a hybrid, international conference at the Senate in the Capitol in Old San Juan on February 22 to 24, 2022: Integrando La Ciencia Y El Arte Del Nacimiento (Integrating the Science and Art of Birth).[xiv] The goal of the conference was to move forward on implementing integrated perinatal care in Puerto Rico.

More than 300 people registered. Speakers included influential politicians, physicians, birth workers, researchers, lawyers, educators, and advocates. The conference spanned three days. Each day included a welcome address , two morning panels, a networking lunch, two afternoon sessions, and time for community dialogue and planning for next steps. MAM hosted a cultural event on the first evening that included local music and a birthing enactment ceremony. Birth workers, physicians, legislators, students, and public health professionals attended and received continuing education credits.

On the path to better perinatal healthcare

Community partners said the conference was transformative for the birth workers of Puerto Rico. Outcomes included a meeting with lead researchers and politicians to develop a plan to legislatively move forward with integrated care. We are also developing a conference brief that can be used for legislative purposes across the island.

Vanessa Caldari Melendez and I are now planning to create a holistic, collaborative women’s health center in Puerto Rico. The center will focus on clinical service, teaching, and research—so people like my client and my mother can have access to perinatal healthcare that is person-centered, evidence-based, and transformative for pregnant people, their families, and their care teams.

[i] "The JJ Way®," n.d., accessed 31 October, 2022, https://commonsensechildbirth.org/the-jj-way/.

[ii] "What is a Doula," n.d., accessed 31 October, 2022, https://www.dona.org/what-is-a-doula/.

[iii] Isabel M Córdova, "Transitioning: The history of childbirth in Puerto Rico, 1948–1990s" (University of Michigan, 2008).

[iv] Córdova, "Transitioning: The history of childbirth in Puerto Rico, 1948–1990s."

[v] Guillermo Arbona and Annette B Ramirez De Arellano, Regionalization of health services. The Puerto Rican experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

[vi] Eileen Pagan-Berlucchi and Donald N. Muse, "The Medicaid program in Puerto Rico: Description, context, and trends," Health Care Financing Review 4, no. 4 (1983), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/List-of-Past-Articles-Items/CMS1191838.

[vii] Krista Perreira et al., Puerto Rico health care infrastructure assessment, Urban Institute (Washington, DC, 2017).

[viii] Córdova, "Transitioning: The history of childbirth in Puerto Rico, 1948–1990s."

[ix] Holly Horan et al., "La Crisis de la Atención de Maternidad: Experts’ Perspectives on the Syndemic of Poor Perinatal Health Outcomes in Puerto Rico," Human Organization 80, no. 1 (2021), https://doi.org/10.17730/1938-3525-80.1.2, https://doi.org/10.17730/1938-3525-80.1.2.

[x] Brady E. Hamilton, Joyce A. Martin, and Michelle J. K. Osterman, Births: Provisional Data for 2019, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Washington, DC, 2020), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-8-508.pdf.

[xi] Association of Maternal and Child Health (AMCHP), 2018 Puerto Rico: State Profile (2018).

[xii] March of Dimes, 2021 March of Dimes Report Card (2022), https://www.marchofdimes.org/2021-march-dimes-report-card.

[xiii] Horan et al., "La Crisis de la Atención de Maternidad: Experts’ Perspectives on the Syndemic of Poor Perinatal Health Outcomes in Puerto Rico."

[xiv] Revista Integrando La Ciencia Y El Arte Del Nacimiento, (2020), https://issuu.com/cvegacrea/docs/issu_revista_2daconferencia_mam_parto_ciencia.

References

Arbona, Guillermo, and Annette B Ramirez De Arellano. Regionalization of Health Services. The Puerto Rican Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Association of Maternal and Child Health (AMCHP). 2018 Puerto Rico: State Profile. (2018).

"The Jj Way®." n.d., accessed 31 October, 2022, https://commonsensechildbirth.org/the-jj-way/.

Córdova, Isabel M. "Transitioning: The History of Childbirth in Puerto Rico, 1948–1990s." University of Michigan, 2008.

"What Is a Doula." n.d., accessed 31 October, 2022, https://www.dona.org/what-is-a-doula/.

Hamilton, Brady E., Joyce A. Martin, and Michelle J. K. Osterman. Births: Provisional Data for 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Washington, DC: 2020). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr-8-508.pdf.

Horan, Holly, Melissa Cheyney, Yvette Piovanetti, and Vanessa Caldari. "La Crisis De La Atención De Maternidad: Experts’ Perspectives on the Syndemic of Poor Perinatal Health Outcomes in Puerto Rico." Human Organization 80, no. 1 (2021): 2-16.

March of Dimes. 2021 March of Dimes Report Card. (2022). https://www.marchofdimes.org/2021-march-dimes-report-card.

Pagan-Berlucchi, Eileen, and Donald N. Muse. "The Medicaid Program in Puerto Rico: Description, Context, and Trends." Health Care Financing Review 4, no. 4 (1983). https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/List-of-Past-Articles-Items/CMS1191838.

Perreira, Krista, Rebecca Peters, Nicole Lallemand, and Stephen Zuckerman. Puerto Rico Health Care Infrastructure Assessment. Urban Institute (Washington, DC: 2017).

Revista Integrando La Ciencia Y El Arte Del Nacimiento. 2020.