Indonesia’s post‑1998 reforms promised justice, democratic consolidation, and a break from authoritarian rule. Prabowo’s ascent to the presidency, however, raises questions about accountability and human rights protections, writes Yance Arizona (University of Indonesia, 2011), even as formal democratic procedures remain intact.

Introduction

Indonesia’s democratic transition following the collapse of Suharto’s New Order in 1998 was widely regarded as one of the most successful reform experiences in Southeast Asia. Constitutional amendments, direct elections, decentralization, and the establishment of independent institutions—notably the Constitutional Court and the strengthening of the National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM)—marked a decisive break from authoritarian rule. These reforms were expected not only to institutionalize democracy but also to address the legacy of gross human rights violations committed during the New Order, particularly the escalation of state-sponsored terror in its final years.

Indonesian President Suharto announces his resignation in May 1998 amid student-led protests and widespread riots. (© Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

More than two decades later, however, the promise of accountability remains largely unrealized. Instead of democratic consolidation, Indonesia is experiencing a gradual democratic regression, as recorded by the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index (2024). This aligns with the normalization of impunity for serious human rights violations. The election of Prabowo Subianto, the former son-in-law of Suharto, as president in 2024 represents a critical juncture in this trajectory. Although achieved through democratic procedures, his victory carries profound symbolic and political implications. Prabowo’s alleged involvement in the kidnapping and enforced disappearance of pro-democracy activists in 1998 has never been meaningfully addressed through judicial or non-judicial mechanisms. His ascent to the presidency thus raises fundamental questions about the substance of democracy, the integrity of transitional justice, and the future of human rights protection in Indonesia.

This article argues that Prabowo’s presidency not merely reflects unresolved failures of past accountability but actively consolidates a political environment in which impunity becomes normalized. Democratic procedures increasingly operate without democratic substance, while the state’s approach to security, governance, and dissent reveals a return to authoritarian logic reminiscent of the Suharto era. In this context, prospects for resolving gross human rights violations in Indonesia appear increasingly bleak.

Democracy Without Accountability

Formally, Indonesia continues to function as an electoral democracy. Elections are held regularly, political parties compete, and leadership changes occur through constitutional mechanisms. Yet democracy in its substantive sense requires accountability, the rule of law, and the prevention of abuses of power. The persistence of impunity for gross human rights violations represents a fundamental rupture in this framework.

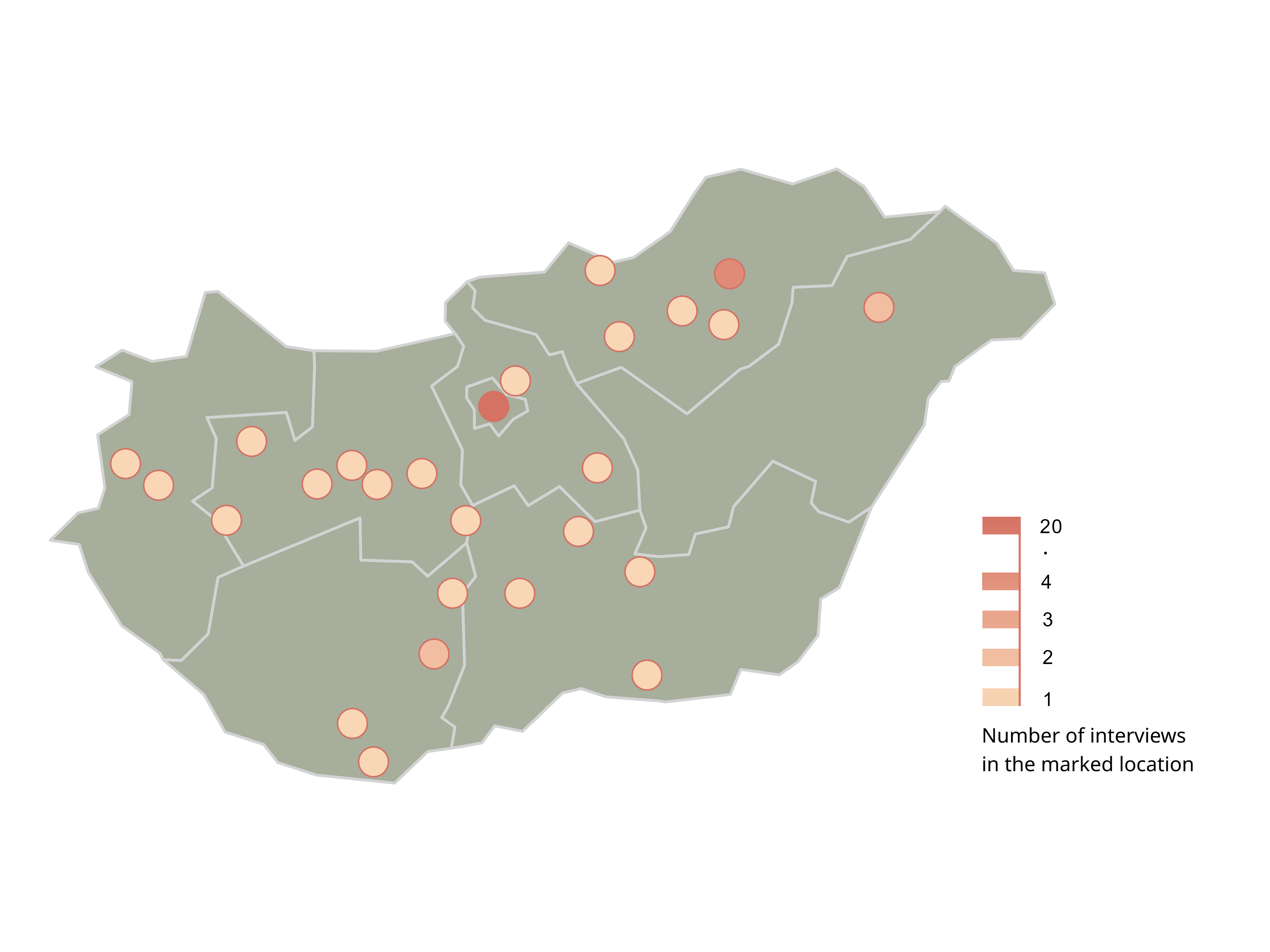

Since the Reformasi (post-1998) period, successive governments have failed to ensure accountability in major cases, including the 1965–66 mass killings, enforced disappearances in the late 1990s, the Trisakti and Semanggi shootings, and systematic abuses in Papua. Despite extensive investigations conducted by Komnas HAM, these cases have consistently stalled at the prosecutorial stage. The Attorney General’s Office has repeatedly refused to pursue them, reflecting not technical incapacity but political reluctance to confront powerful military and political elites.

Prabowo’s election must be understood against this background of structural impunity. His political rehabilitation was possible precisely because the process of transitional justice remained incomplete. The absence of legal consequences enabled his return to formal politics, his normalization as a public figure, and eventual rise to the presidency. This trajectory demonstrates how impunity perpetuates itself across generations of power.

Electoral Victory and the Normalization of Impunity

A visual contrast in the political career of Prabowo Subianto: on the left, his 1998 dismissal from the military following allegations of involvement in the abduction of pro-democracy activists; on the right, his 2024 receipt of an honorary general badge from President Joko Widodo, shortly after winning the presidential election with Gibran Rakabuming Raka—Jokowi’s son—as his running mate.

Supporters of Prabowo often argue that his electoral victory confers democratic legitimacy and should put past allegations to rest. This argument conflates electoral success with moral and legal exoneration. Democratic elections determine who governs, but they do not absolve responsibility for serious crimes. When democratic mandates are used to shield unresolved allegations of gross human rights violations, democracy itself becomes an instrument of impunity.

The political narrative surrounding Prabowo’s presidency emphasizes reconciliation without truth, stability without justice, and development without rights. Human rights violations are reframed as historical controversies, national security necessities, or unfortunate excesses of the past that should not impede national unity. This narrative undermines the principle that crimes against humanity are not subject to political compromise or historical amnesia. Elevating a figure associated with an unresolved past to the highest executive office sends a powerful message that accountability is optional and that power can erase responsibility.

Militarization of Civil Governance

One of the clearest indicators of democratic regression under Prabowo is the expanding role of the military in civilian governance. Although Suharto’s central doctrine of dwifungsi ABRI—the “dual function” of the military in both the defense and civilian spheres—was abolished under Reformasi, its logic is re-emerging through legal and institutional practices. Revisions to the Military Law in 2025 now permit active officers to occupy several civilian posts, while retired and active military figures increasingly dominate ministries and state-owned enterprises.

This militarization has profound implications for human rights. Military institutions prioritize command, hierarchy, and security rather than democratic deliberation and rights protection. When military actors dominate civilian spaces, governance tends to privilege order over accountability.

In regions such as Papua, this approach has intensified repression. Militarization there aligns with government projects to clear approximately 2 million hectares of land for food production through deforestation, despite opposition from Papuan indigenous communities. Security operations continue to be framed as responses to separatism rather than potential sources of human rights violations. The normalization of military involvement reinforces institutional cultures that historically enabled impunity.

Criminalization of Dissent and Reversal of Direct Local Elections

Another telltale sign of democratic regression is the systematic narrowing of civic space. Activists, students, and civil society organizations increasingly face surveillance, intimidation, and criminal prosecution for protests and expressions critical of government policy. Demonstrations are frequently met with excessive force, arbitrary arrests, and charges under vague criminal provisions. After the mass protest in August 2025, 13 people died due to violence by security forces, and 703 individuals were detained and prosecuted. They are political prisoners who were tried for their legitimate expression in public. This pattern reflects a governing philosophy that treats dissent as a threat rather than a democratic resource. Laws on public order, electronic information, and national security are used to silence critics, creating a chilling effect on political participation. Many targeted activists are those who consistently demand accountability for past human rights violations. By criminalizing their actions, the state suppresses both contemporary dissent and collective memory of past injustices.

Protestors in Surabaya clash with police in August 2025. Government buildings were torched and the homes of parliament members were looted in Indonesia following a violent crackdown on civil dissent. (© Robertus Pudyanto/Getty Images)

The proposal to revert the selection of regional heads from direct elections to appointments by regional legislatures represents another significant democratic setback. Direct local elections were one of the most tangible achievements of Reformasi, enhancing political participation, accountability, and local autonomy. While the system has its flaws, its abolition would concentrate power within political elites and weaken popular control over local governance.

The justification for this reversal often rests on efficiency, cost reduction, or political stability. Yet these arguments obscure the broader democratic implications. Removing direct elections diminishes citizens’ ability to hold local leaders accountable and reinforces oligarchic control over political processes. It also aligns with a broader trend toward centralization and elite-driven decision-making.

In the context of human rights, this shift is particularly concerning. Local elections have often provided avenues for marginalized communities to influence governance and challenge abusive practices. Their removal would further distance decision makers from affected populations, reducing opportunities for rights-based advocacy at the local level.

Rewriting History and the Failure of Transitional Justice Mechanisms

The rehabilitation of authoritarian figures illustrates the depth of democratic regression. President Prabowo’s decision on November 11, 2025, to grant national hero status to former President Suharto represents an official rewriting of history. Suharto was forced to resign in 1998 amid mass protests against corruption, repression, and widespread human rights violations. Honoring him erases victims, understates suffering, and legitimizes authoritarian governance.

This revisionism reshapes collective memory and signals that justice is subordinate to political power. It also reflects the broader failure of Indonesia’s transitional justice framework. Judicial mechanisms have been ineffective, while non-judicial initiatives have been delayed or diluted. Under Prabowo’s leadership, meaningful accountability appears increasingly unlikely, given his personal history and reliance on military and elite support. Without accountability, the structural conditions that enabled past abuses persist, embedding impunity within political culture.

Indonesia’s experience reflects a broader global trend in which democratic procedures are used to legitimize authoritarian practices. Elections and constitutional forms remain intact, but their substance is hollowed out. Democracy becomes a shield for power rather than a constraint upon it. Under Prabowo, democratic mandates coexist with policies that weaken civilian control, suppress dissent, and reinvent authoritarian legacies. As a result, Indonesia risks consolidating an illiberal democracy in which elections legitimize authority while justice remains perpetually deferred.

Bibliography

Aspinall, Edward, and Ward Berenschot. Democracy for Sale: Elections, Clientelism, and the State in Indonesia. Cornell University Press, 2019. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvdtphhq.

Crouch, Harold. The Army and Politics in Indonesia. Cornell University Press, 1988. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvv417br.

Power, Thomas P. “Jokowi’s Authoritarian Turn and Indonesia’s Democratic Decline.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 54, no. 3 (2018): 307–38. doi:10.1080/00074918.2018.1549918.

Robinson, Geoffrey B. The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965–66. Princeton University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc774sg.