The following article is based on Bulgaria and Japan: From the Cold War to the Twenty-first Century, an exhaustively researched 2009 book by Evgeny Kandilarov—a Sylff fellow at Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski,” who used his fellowship to conduct research at Meiji University in Japan in 2005. The Tokyo Foundation asked the author, who is now an assistant professor at his alma mater, to summarize his findings, which have revealed intriguing patterns in the history of bilateral ties and international relations over the past several decades.

* * *

The book Bulgaria and Japan: From the Cold War to the Twenty-first Century is almost entirely based on unpublished documents from the diplomatic archives at the Bulgarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In order to clarify concrete political decisions, many documents from the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, Comecon, and State Committee for Culture were used. These documents are available at the Central State Archives of the Republic of Bulgaria. For additional information, memoirs of eminent Bulgarian political figures and diplomats who took part in the researched events were also used.

This article aims to give a brief overview of the political, economic, and cultural relations between Bulgaria and Japan during the Cold War and the subsequent period of Bulgaria’s transition to democracy and a market economy.

Exhaustive research on the bilateral relationship between Bulgaria and Japan have revealed specific reasons, factors, and causes that led to fairly intense economic, scientific, technological, educational, and cultural exchange between the two countries during the Cold War. Furthermore, the study raises some important questions, perhaps the most intriguing one being: Why did the relationship rapidly lose its dynamics during the transition period, and what might be the reasons for this?

The study also poses a series of questions concerning how bilateral relations influenced the economic development of Bulgaria during the 1960s and 1980s, throwing light on the many economic decisions made by the Bulgarian government that were influenced by the Japanese economic model.

Five Distinct Stages of the Relationship

The analysis of Bulgaria-Japan relations can be divided into two major parts. The chronological framework of the first part is defined by the date of the resumption of diplomatic relations between Bulgaria and Japan in 1959 and the end of state socialism in Bulgaria in 1989, coinciding with the end of the Cold War. This timeframe presents a fully complete period with its own logic and characteristics, following which Bulgaria’s international relations and internal policy underwent a total transformation at the beginning of the 1990s.

The second part of the analysis covers the period of the Bulgarian transition from state socialism to a parliamentary democracy and market economy. This relatively long period in the development of the country highlighted the very different circumstances the two countries faced and differences in their character.

The inner boundaries of the study are defined by two mutually related principles. The first is the spirit of international relations that directly influenced the specifics of the bilateral relationship, and the second is the domestic economic development of Bulgaria, a country that played an active role in the dynamics of the relationship. In this way, the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s (through 2007, when Bulgaria joined the EU), and the years since 2007 represent five distinct stages in the relations between Bulgaria and Japan.

The first stage began with the resumption of diplomatic relations in 1959. This was more a consequence of the general change in international relations in the mid-1950s than a result of deliberate foreign policy. After the easing of Cold War tensions between the two military and political blocs and the restart of dialogue, the whole Eastern bloc began normalizing its relations with the main ideological rival, the United States, as well as with its most loyal satellite in the Asia-Pacific region—Japan. From another point of view Japanese diplomatic activity toward Eastern Europe, including Bulgaria, was motivated mostly by the commercial and economic interests of Japanese corporations looking to extend their markets.

This period in Bulgarian-Japanese relations in the 1960s was characterized by mutual study and search for the right approach, the setting up of a legislative base, and the formulation of main priorities, aims, and interests.

Analyses of documents from the Bulgarian state archives show that Bulgaria was looking for a comprehensive development of the relationship, while Japan placed priority on economic ties and on technology and scientific transfer.

Budding Commercial Ties

One of the most important industries for which the Bulgarian government asked for support from Japan was electronics, which was developing very dynamically in Japan. In the mid-1960s Bulgaria signed a contract with one of Japan’s biggest electronics companies, Fujitsu Ltd. According to the contract, Bulgaria bought a license for the production of electronic devices, which were one of the first such devices produced by Bulgaria and sold on the Comecon market. The contract also included an opportunity for Bulgarian engineers to hone their expertise in Japan.

In the 1960s the first joint ventures between Bulgaria and Japan were established. In 1967 the Bulgarian state company Balkancar and the Japanese company Tokyo Boeki create a joint venture called Balist Kabushiki Kaisha. Another joint venture that was established was called Nichibu Ltd. In 1971 these two companies merged into a new joint venture, Nichibu Balist, engaged in trading all kinds of metals and metal constructions, forklifts and hoists and spare parts for factories, ships (second hand), marine equipment, spare parts, electronics, pharmaceuticals, and chemical products.

In 1970 Bulgaria and Japan signed an Agreement on Commerce and Navigation, which was the first of its kind signed by the Bulgarian government with a non-socialist country. According to the agreement, the two countries granted each other most-favored-nation treatment in all matters relating to trade and in the treatment of individuals and legal entities in their respective territories.

At the end of this stage of Bulgarian-Japanese bilateral relations, by participating in the Expo ’70 international exhibition, Bulgaria already had a clear idea of the “Japanese economic miracle” and how it could be applied to Bulgaria’s economic growth.

The Bulgarian government led by communist ruler Todor Zhivkov were very much impressed and influenced by Japan’s industrial, scientific, and technological policy, which led to the so called Japanese miracle. That is why the economic reforms and strategies adopted in Bulgaria over the following few years, although conducted in a completely different social and economic environment, were influenced to some extent by the Japanese model, especially in the field of science and technological policy.

Peak of Political and Economic Activity

The second stage in bilateral relations in the 1970s marked the peak of political and economic activity between the two countries. The goals set during the previous period were pursued and achieved slowly and steadily. The legislative base was broadened, and the number of influential Japanese partners increased. The international status quo in East-West relations, marked by the Helsinki process, presented the possibility for Bulgaria and Japan to enjoy a real “golden decade” in their relations.

In 1972 the Japan-Bulgaria Economic Committee for the development of trade, economic, and scientific and technological ties between the two countries was established in Tokyo. Committee participants included a number of large Japanese manufacturers, financial institutions, and trading companies. The head of the Committee was Nippon Seiko (NSK) President Hiroki Imazato. The same year in Sofia, Bulgaria established the Bulgaria-Japan Committee for Economic, Science, and Technical Cooperation, headed by Minister of Science, Technologies, and Higher Education Nacho Papazov.

In the mid-1970s the Bulgarian government undertook some legislative changes regarding the rules for foreign company representation in Bulgaria. These changes were influenced mainly by the attempt by the Bulgarian government to encourage the further development of Bulgarian-Japanese economic relations. After the legislative changes Japanese companies received the right to open their own commercial representative offices in Bulgaria, and in just a few years 10 Japanese companies opened offices: Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sumitomo, C. Itoh, Fujitsu, Tokyo Maruichi Shoji, Nichibu Balist, Marubeni, Nissho Iwai, and Toyo Menka Kaisha. In 1977 the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) also opened an office, greatly contributing to the promotion of the trade and economic relations between Bulgaria and Japan.

Historic Summit Meeting

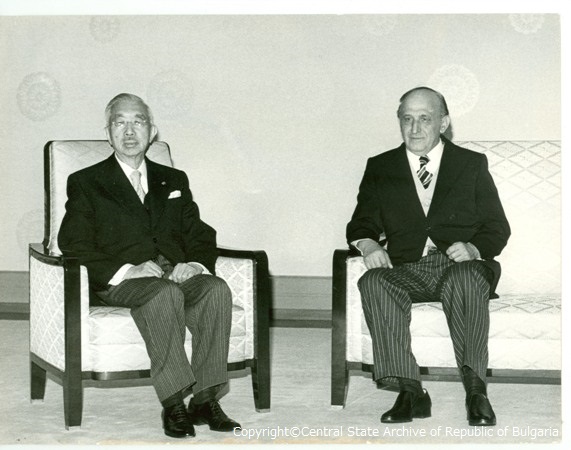

A political expression of the peak of Bulgarian-Japanese relations during the 1970s was the first official summit visit in the history of bilateral diplomatic relations—the visit by Bulgarian state leader Todor Zhivkov to Japan in March 1978 for a meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda.

During the visit, the two sides agreed to establish a Joint Intergovernmental Commission for Economic Cooperation, which has held working sessions every year, engaging both governments to further promote and extend the bilateral economic relationship.

Following the state visit by Todor Zhivkov, the Bulgarian government created a very detailed strategic program for the development of Bulgarian-Japanese relations for the decade up to 1990. The main focus of the program was the following idea: “The strategic direction in the economic relations between Bulgaria and Japan consists in the rational use and implementation of modern and highly effective Japanese technologies, equipment and production experience for the promotion of the quality and efficiency of the Bulgarian economy.”

Another key point was that the Bulgarian government would focus its efforts on strengthening cooperation with leading Japanese companies in such fields as electronics and microelectronics, automation and robotics, heavy industries, chemicals, electronics, and engineering.

In response to the Bulgarian state visit in 1978, the next year, in October 1979, Bulgaria was visited by Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko as the official representatives of Emperor Hirohito.

1980s: Broadening Spheres of Cooperation

During the third period of Bulgarian-Japanese relations, the momentum of the preceding stages still kept the relationship stable and growing. The sphere of cooperation and mutual interest widened, and the Bulgarian government relied more on the Japanese support and the advantages offered by the Japanese economic model.

At the beginning of the 1980s the Bulgarian government undertook another step toward the liberalization of the Bulgarian economy. It gave an opportunity for Western companies to invest in Bulgaria by concluding contracts for industrial cooperation and creating associations. These changes in the Bulgarian economy caused great interest among Japanese economic circles, and within the next few years six Bulgarian-Japanese joint companies were created. The names and activities of the joint companies were as follows:

— Fanuc-Mashinex with the participation of Japanese company Fanuc Co: Service and production in the fields of electronics, automation, and engineering.

— Atlas Engineering with the participation of Japanese companies Mitsui, C. Itoh, Toshiba, and Kobe Steel: Design, supply, and implementation of projects in Bulgaria and third countries in the fields of mechanical engineering, chemicals, and metallurgy.

— Sofia-Mitsukoshi with the participation of Japanese companies Mitsukoshi and Tokyo Maruichi Shoji: Production and trade in the field of light industry as well as the reconstruction of department stores.

— Tobu-M.X.: Manufacture and sale of machinery for magnetic abrasive treatment of complex-shaped parts. Production was based on Bulgarian technology, and the products were sold in Japan and in third countries.

— Medicom Systems with the participation of Japanese company Tokyo Maruichi Shoji: Research, production, and sale of equipment and software for the medical and education markets.

— Farmahim-Japan with the participation of Japanese company Marubeni: Collaboration in the pharmaceutical field.

1990s: Transformation of the Relationship

The subsequent crisis in East-West relations in the 1980s, the growing economic crisis in the Communist bloc, and changes in the political leadership in Moscow brought about the end of the Cold War and the beginning of a new era in international relations. During the 1990s, these new factors completely transformed the relationship between Bulgaria and Japan.

In the next period, during which Bulgaria began a long and arduous transition to a democratic political system and functioning market economy, an abrupt switch came about in the direction of Bulgarian foreign policy. The governing parties during this period made every effort to incorporate Bulgaria into the Euro-Atlantic military and economic structures, namely, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union.

This required a great deal of effort to transform the political and economic systems. The focusing of national energy on these social transformations created a totally different environment for Bulgaria-Japan relations. Bulgaria became a developing country and was placed in an unequal position in terms of the international hierarchy. For a long time, relations between the two countries consisted largely of Japanese disbursements of official development assistance (ODA).

Despite the dialogue between Bulgaria and Japan from 1959 to 1989, the 1990s was a period of steady decline and stagnation in the bilateral relationship, being reduced, to a large extent, to one between donor and recipient.

All this led to a paradoxical situation: economic relations between Bulgaria and Japan were much closer when the countries were politically and ideologically far apart than during the period after 1989, when they stood in the same ideological framework. The underlying reasons for this are related to the question of what were the driving forces of the relationship during the Cold War.

Nurturing a New Partnership

A detailed study of the relationship between 1959 and 1989 shows that for the most part the initiative came mainly from the Bulgarian side, which showed keen interest in and reaped benefits from the relationship. Bulgaria was driven by commercial and economic interests and the need for scientific and technological cooperation. Moreover, Japan was both a good model and a suitable partner for Bulgaria. Japan saw in Bulgaria and other socialist countries an opportunity to expand its export markets and to import cheaper food commodities and raw materials.

At the same time, ties with a highly developed country like Japan provided an opportunity for the Bulgarian government to identify the defects and shortcomings of the closed, centralized, planned economy. This underlined a persistent set of problems, the major one being the lack of competitiveness of Bulgarian products stemming from poor quality, low labor efficiency, poor level of technology, unstable stock exchange, limitations in the number and variety of goods, mediocre design, and the failure to adapt to a highly dynamic and competitive market environment.

As late as January 1, 2007, both countries took a step to set up a new partnership framework on equal terms. After Bulgaria joined the EU, relations between the two countries became almost entirely dependent on the geopolitical, economic, and to some extent cultural interests of the respective counties in the region. From this perspective, the starting points of the relations between Bulgaria and Japan at the beginning of the twenty-first century did not seem very strong. This could be clearly seen in the empirical data on Japanese investment in Bulgaria, financial transactions, the traffic of tourists, cultural presence, and other areas, as well as in the peripheral position of Bulgaria in Japan’s foreign strategy toward the region, underlined by then Japanese foreign minister Taro Aso’s 2006 concept called the Arc of Freedom and Prosperity.

Unfortunately, even almost seven years after Bulgaria joined the EU there has not been any significant change in Bulgarian-Japanese relations, which remain very much below their optimal potential. The reasons for this can be found both in the lack of political and economic stability in Bulgaria as well as in the continuing economic instability of Japan over the last 20 years. Whether Japan and Bulgaria will once again see a merging of interests and revive a mutually beneficial relationship is a matter for another analysis. The most important thing is that there is already a very good base for a fruitful relationship, even though it was set during the Cold War, and it should be used as a starting point in the attempts by the Bulgarian government and its Japanese partners to find a more efficient and beneficial approach in developing bilateral relations.