Ghana’s renewable energy ambitions highlight Africa’s clean energy paradox: technically sound policies coexist with persistent implementation barriers, writes Seth Owusu-Mante (Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, 2019), hindering progress toward energy security, sustainability, and inclusive growth.

* * *

Climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing threats to sustainable development, compelling governments worldwide to adopt ambitious policies to accelerate the global transition to clean energy.

In Africa, the stakes are especially high: as the region most vulnerable to climate impacts (IEA 2023a), African countries must adapt to intensifying climate risks and at the same time contribute meaningfully to global mitigation efforts, all against the backdrop of persistent socio-economic challenges.

Crucially for the continent, mitigating the climate crisis by leveraging its abundant renewable energy resources is not only a climate imperative but also a pathway to job creation (IEA 2023b; Hanna et. al. 2024), enhanced energy access (Fagbemi 2025; Alex-Oke et al. 2025), and inclusive economic growth for millions currently without electricity (GIZ 2024; Alex-Oke et al.).

Ghana’s experience encapsulates both the promise and the pitfalls of Africa’s clean energy transition. Over the past decade, the country has developed one of the most comprehensive renewable energy policy frameworks on the continent, guided by policies and legislation, such as the Renewable Energy Act, 2011 (Act 832), the Renewable Energy (Amendment) Act, 2022 (Act 1045) , the Renewable Energy Master Plan (2019), and the National Energy Transition Framework (2022). These were designed to diversify the national energy mix, enhance energy security, expand energy access, and align the country with global energy and decarbonization targets under the Paris Agreement.

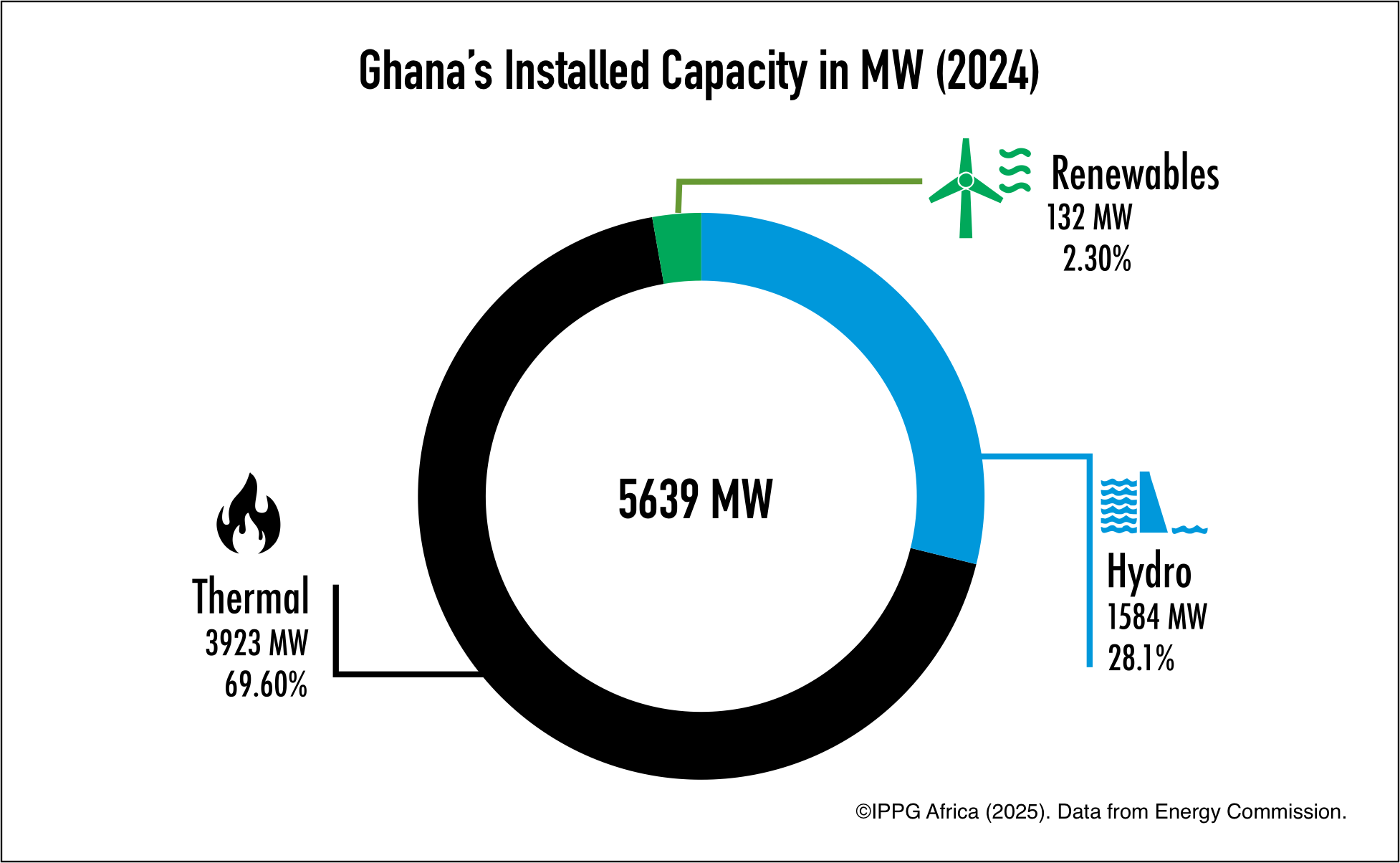

However, despite the technical soundness of these policies, Ghana’s renewable energy deployment remains far below expectations. As of 2025, only 132 MW of non-hydro renewables have been installed, representing just 2.3% of national capacity (see figure below), compared to the 1,363 MW target set for 2030 by the Renewable Energy Master Plan (2019). This stark gap between ambition and reality provided the central motivation for my research.

Source: International Perspective for Policy Governance (IPPG Africa 2025).

Sound Policy Design

The study set out to investigate both policy and implementation gaps within Ghana’s renewable energy sector and to assess their implications for energy access, reliability, security, and climate goals. To accomplish this, a mixed-methods approach was employed.

First, a documentary review examined Ghana’s major renewable energy frameworks, situating them within the broader African and global policy context. Second, a survey of energy experts was conducted, and the results were further investigated through interviews with policymakers, regulators, government officials from the Ministry of Energy and Green Transition, Bui Power Authority, Volta River Authority, Electricity Company of Ghana, as well as project developers, academics, civil society experts, and community representatives. This combination of qualitative and quantitative data enabled a robust assessment of the perceived effectiveness of existing policies, the most critical barriers to their success, and the lived realities of government officials tasked with implementation.

The findings reveal that Ghana’s policy frameworks are widely regarded as comprehensive and well-structured. Stakeholders highlighted the Renewable Energy Master Plan and the National Energy Transition Framework as the most effective policy initiatives, indicating the country’s capacity to adopt technically sound strategies.

Yet, the findings also demonstrate that the country’s sound policy design is undermined by persistent policy gaps. Chief among these is the absence of adequate policy instruments, such as tax credits, subsidies, and other financial incentive policies, that could attract private investments to make renewables competitive with conventional sources.

Respondents also pointed to weak integration of renewable energy into broader national energy planning, the absence of systematic policy review mechanisms, and the lack of policy provisions in emerging areas such as storage and battery utilization. Collectively, these omissions have created a fragmented policy environment that fails to adapt to technological changes and evolving market dynamics.

A group photo following an interview with Director of Renewable Energy Ing. Peter Acheampong of Bui Power Authority, second from left, flanked by project field supervisor Eric Agyemang, far left, and research assistants Nii Ayikwei Quaye, far right, and Emmanuella Biney.

Barriers to Implementation and Institutional Challenges

The study also uncovered a set of equally significant implementation gaps. The most frequently cited implementation barrier was limited access to financing mechanisms, with nearly 90% of the survey respondents emphasizing the inability of developers to secure long-term, affordable finance. Local banks view renewable projects as high-risk ventures, and the absence of government guarantees or innovative financing instruments further limits investment. Political interference and inconsistent leadership also emerged as recurring themes, with stakeholders noting how renewable energy initiatives are often tied to particular administrations and lose momentum when political priorities shift. Weak regulatory enforcement compounded these challenges, as institutions tasked with oversight often lack the capacity or authority to ensure compliance and accountability. Together, these implementation gaps erode investor confidence and slow down the deployment of projects that could otherwise contribute meaningfully to Ghana’s energy transition.

The consequences of these gaps extend well beyond missed megawatts. They jeopardize Ghana’s energy security by leaving the country over-reliant on hydropower, which is vulnerable to seasonal fluctuations, and on imported fossil fuels, which expose the economy to volatile international markets, resulting in the country’s over $3 billion energy sector debt. They also threaten Ghana’s ability to meet its nationally determined contributions (NDC), which include reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 64 MtCO₂e by 2030.

Moreover, the lack of progress undermines opportunities for job creation, industrial development, and equitable access to modern energy services. Although Ghana has one of the highest electricity access rates in Sub-Saharan Africa at nearly 90%, the persistence of implementation failures means that energy remains unreliable, expensive, and insufficiently sustainable.

This research carries important implications for both academic scholarship and societal practice. For scholars, it contributes to the growing body of literature on renewable energy transitions by clearly distinguishing between gaps in policy design and failures in policy implementation. Previous research has often emphasized technical potential or legislative frameworks without interrogating why outcomes remain consistently underwhelming. Through the integration of empirical evidence from surveys and interviews with government officials, policymakers, and other key energy experts, this study offers a more nuanced understanding of the institutional, financial, and political dynamics that constrain energy transitions in developing country contexts.

Project RAs Emmanuella Biney and Nii Ayikwei Quaye with their field supervisor Eric Agyemang, left, interviewing Manager for Renewable Energy Edward Ochire and Assistant Electrical Engineer Osborn Amoh of the Electricity Company of Ghana Limited, right.

For society, the findings highlight the urgent need to shift the focus from policy formulation to effective implementation by government officials. Addressing financing barriers is paramount. Instruments such as sovereign guarantees, green bonds, and put-call option agreements could reduce investor risk and unlock private capital for renewable projects. Strengthening regulatory institutions, enhancing inter-agency coordination, and insulating energy policy from partisan politics are equally critical steps. A more transparent and participatory approach, including periodic policy reviews and stronger community engagement, would ensure that renewable energy strategies remain responsive to technological changes and societal needs. Without these measures, Ghana risks perpetuating a cycle of ambitious targets and underwhelming results.

Lessons and Implications for Ghana and Beyond

In sum, this study demonstrates that Ghana’s renewable energy transition is not merely a technical project but a deeply institutional and political endeavor. The country possesses abundant renewable resources, proven policy ambition, and a demonstrated ability to execute large-scale energy programs, as shown by its electrification achievements.

What remains lacking is the translation of policies into bankable projects, enforceable regulations, and resilient institutions. Bridging this gap will not only strengthen Ghana’s energy security and economic resilience but will also position the country as a continental leader in renewable energy.

The lessons from Ghana resonate beyond its borders, offering insights for other African nations grappling with similar challenges. Moving decisively to address policy and implementation gaps would allow Ghana to transform its renewable energy sector from a story of missed opportunities into one of genuine leadership in sustainable development and inspiration for other African countries.

References

Alex-Oke, Temidayo, Olusola Bamisile, Dongsheng Cai, Humphrey Adun, Chiagoziem Chima Ukwuoma, Samaila Ado Tenebe, and Qi Huang. 2025. “Renewable energy market in Africa: Opportunities, progress, challenges, and future prospects.” Energy Strategy Reviews 59: 101700.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). 2024. The Renewable Energy Transition in Africa: Powering Access, Resilience and Prosperity. https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/Study_Renewable%20Energy%20Transition%20Africa-EN.pdf.

Fagbemi, Bomi. 2025. “Africa’s Green Energy Transition.” The Africa Center, May 29. https://theafricacenter.org/news/detail/Africa-s-Green-Energy-Transition.

Hanna, Richard, Philip Heptonstall, and Robert Gross. 2024. “Job creation in a low carbon transition to renewables and energy efficiency: a review of international evidence.” Sustainability Science 19, no. 1: 125–50.

International Energy Agency (IEA). 2023a. Africa Energy Outlook 2022: Special Report. Revised version, May 2023. Paris: IEA. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/220b2862-33a6-47bd-81e9-00e586f4d384/AfricaEnergyOutlook2022.pdf.

International Energy Agency. 2023b. World Energy Employment 2023. Paris: IEA. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/8934984a-0d66-444f-a36f-641a4a3ef7de/World_Energy_Employment_2023.pdf.

International Perspective for Policy & Governance (IPPG Africa). 2025. “The Case for Ghana’s Renewable Energy Transition: A Path to Sustainability and Economic Resilience.” (Authored by Seth Owusu-Mante.) April 25. https://www.ippgafrica.org/blog-post/the-case-for-ghanas-renewable-energy-transition-a-path-to-sustainability-and-economic-resilience/.