Otgontuya Dorjkhuu, who received a Sylff fellowship in 2009 at National Academy of Governance, served as a moderator in Mongolia’s first deliberative poll. Drawing on this experience and on the results of deliberative polls conducted in six countries including Mongolia, Otgontuya discusses why the concept of Deliberative Polling® is crucial and how citizen participation plays a key role in public policy.

* * *

Deliberative Polling® is a novel concept for most people, even though experiments have been conducted in many countries around the world, including the United States, Britain, other countries in the European Union, Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Ghana. A broad range of issues are discussed in a DP event, such as the economy, education, health, the environment, elections, and political reform. This method of polling is especially suitable for issues about which the public may have little knowledge or information or where the public may have failed to confront the trade-offs applying to public policy. It is a social science experiment and a form of public education in the broadest sense (Center for Deliberative Democracy, December 2003).

Mongolia’s First Deliberative Poll

Mongolia’s first deliberative poll was held on December 12–13, 2015, under the title of “Citizens’ Participation: Tomorrow’s City.”

On December 12–13, 2015, a scientific random sample of residents of Ulaanbaatar1 gathered for two days of deliberation about major infrastructure projects proposed in the capital city’s master plan. The program consisted of small group discussions and plenary sessions exploring arguments for and against 14 large projects that would require borrowing, during which questions were posed to experts. All of the deliberative events were broadcast live on three television channels in Mongolia.

The 317 individuals who completed the two days of deliberation can be compared in both their attitudes and their demographics with the remaining 1,185 who took the initial survey. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in gender, education, age, employment status, marital status, or income (CDD, January 2016).

The three project proposals that received the highest ratings after deliberation share an environmental focus on clean energy, energy efficiency, and waste disposal. The top proposal, “improved heating for schools and kindergartens,” had a mean rating of 0.94 out of 1. It consisted of upgrading the insulation and technology used in public school heating systems. The runner-up proposal, “protection of Tuul and Selbe rivers,” featured preliminary efforts to improve water flow and rehabilitate the rivers. Although support for the project went down somewhat after deliberation, its rating was still the second highest at 0.93. The rating for the third most popular proposal, “an eco park with two waste recycling facilities,” was largely unchanged after deliberation at 0.92.

These results are consistent with the public’s strong environmental priorities expressed in other questions in the survey (CDD, January 2016). Both before and after deliberation, participants were highly focused on policy goals aimed at reducing air, water, and land pollution. Air pollution is the biggest issue for all citizens of Ulaanbaatar city, especially in winter.

Evaluating the Process

Evaluation is one of the most important aspects of the Deliberative Polling process. For comparison, I selected six countries in different regions (Asia, Africa, and North America) where deliberative polls had been conducted.

Participants in all of these countries rated the process highly. On average, 91.6% approved of “the overall process” in the six selected countries. Evaluations of the small group discussions and plenary sessions were similarly high, with anywhere from 86.7% to 93.0% of participants giving positive responses to all of the questions. An average of 91.3% felt that their group moderator “provided the opportunity for everyone to participate in the discussion,” while 90.3% thought that their group moderator “sometimes tried to influence the group with his or her own views.”

Participants in Mongolia, Britain, California (United States), and Ghana felt that they had learned a lot about people who were very different from them. Mongolian, British, and Ghanaian participants rated the process more highly than those of the other three countries .

Table 1. Evaluations of the Deliberative Polling Process by Country

|

Evaluations |

Mongolia |

Japan |

South Korea |

Britain |

California |

Ghana |

|

The overall process |

94.3% |

85.6% |

92.2% |

99% |

89% |

90% |

|

Participating in the small group discussions |

95.0% |

87.4% |

94.8% |

95% |

||

|

Meeting and talking to delegates outside of the group discussions |

93.4% |

79.0% |

94% |

|||

|

The large group plenary sessions |

95.0% |

78.6% |

84.2% |

89% |

||

|

My group moderator provided the opportunity for everyone to participate in the discussion. |

98.1% |

82.4% |

90% |

91% |

95% |

|

|

The members of my group participated relatively equally in the discussions. |

97.5% |

61.0% |

73% |

|||

|

My group moderator sometimes tried to influence the group with his or her own views. |

90.9% |

82.8% |

95% |

93% |

90% |

|

|

I learned a lot about people very different from me—about what they and their lives are like. |

95.6% |

91% |

88% |

99% |

Notes: Figures in the table are collected from the reports on Deliberative Polling conducted in each country. With regard to the first four items in the list, respondents were asked to rate on a scale of 0 to 10 (where 0 is “a waste of time,” 10 is “extremely valuable,” and 5 is exactly in the middle) how valuable each component was in helping them clarify their positions on the issues. For the latter four items, they were asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each statement.

Knowledge Gains

The knowledge index can be used as an indicator to explain changes in opinion on policy goals. In most of the cases that I reviewed, the percentage of those who correctly answered questions rose significantly after deliberation. For instance, in the case of Mongolia, correct responses regarding the percentage of households in Ulaanbaatar city that live in apartments increased by 12 points from 47% before deliberation to 59% after (CDD, January 2016).

In Japan, the overall knowledge gains were substantial and statistically significant; an average knowledge gain of 7.4% was seen in the six questions that were asked. Participants who correctly answered what percentage of Japan’s electricity generation comes from nuclear power (about 30%) increased 13.7 points from 47.4% to 61.1% (CDD, September 2012).

In Ghana, only 21.6% of participants knew prior to deliberation that the percentage of the Tamale population with daily access to potable water was about 40%. After deliberation, the percentage rose significantly to 37.6%, an increase of 16 points (CDD and West Africa Resilience Innovation Lab, December 2015).

Among the California participants, correct responses to the eight questions asked increased substantially by 18 points overall (CDD, October 2011). The knowledge index clearly showed relevant and substantial knowledge gains among the participants.

The Moderator’s Role

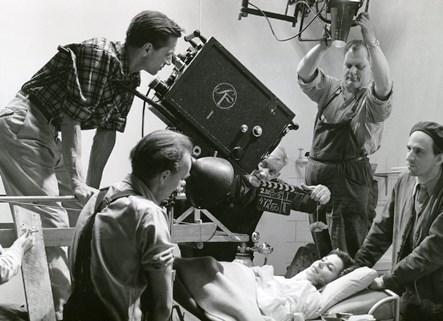

The members of Group 10, which was moderated by Otgontuya Dorjkhuu (back row far right) with the mayor of Ulaanbaatar city and Professor James Fishkin of Stanford University seated at front row center.

Deliberative Polling is an attempt to use public opinion research in a new, constructive, and nonpolitical manner, and moderators play a key role in the process. They ensure fruitful and civil exchange between participants and let all points of view emerge. With their help and support the participants can find their voices, discover their views, and develop their own opinions (CDD, December 2003). In the Ulaanbaatar event, the 317 deliberators were randomly assigned to 20 small groups led by trained moderators2. The moderators helped deliberators go through discussions of all projects according to the agenda presented in the briefing materials. The two-day process alternated between small group discussions and plenary sessions until all 14 projects were discussed.

The project proposals were rated3 on the same scale before and after deliberation. Citizen opinions both before and after indicated that all of the proposals were thought to be desirable.

In Conclusion

Deliberative Polling is a useful approach to increase citizens’ participation and voice in the policy making process. Following the deliberation in Ulaanbaatar, the participants changed their views in many statistically significant ways, had greater knowledge, and together identified specific policy solutions that could help address the country’s priority issues.

As a moderator for Mongolia’s first deliberative poll, I found that participants were very enthusiastic and exchanged their views without reservation. My observations from the event leads me to believe that, given an opportunity like this to participate in discussions on critical issues, people would be willing to express their opinions anytime on any topic. According to reports on Deliberative Polling events that have been conducted in other countries, the overall knowledge gains after deliberation were substantial and statistically significant.

Finally, it can be concluded that Deliberative Polling not only is a form of public consultation but can also serve as a means of improving public knowledge.

References

Center for Deliberative Democracy (December 2003). What is Deliberative Polling®? Retrieved December 13, 2015, from http://cdd.stanford.edu/what-is-deliberative-polling/

Center for Deliberative Democracy (January 2016). Mongolia's First Deliberative Poll: Initial Findings From "Tomorrow's City."

Center for Deliberative Democracy (January 2012). First Deliberative Polling in Korea: Issue of Korean Unification, Seoul, South Korea.

Center for Deliberative Democracy (January 2010). Final Report: Power 2010—Countdown to a New Politics.

Center for Deliberative Democracy (October 2011). What's Next California? A California Statewide Deliberative Poll for California's Future.

Ulaanbaatar City. Retrieved December 13, 2015, from ulaanbaatar.mn

Center for Deliberative Democracy and West Africa Resilience Innovation Lab (December 2015). Deliberative Polling in Ghana: First Deliberative Poll in Tamale, Ghana.

National Statistical Office of Mongolia (2015). Statistical Yearbook 2014.

Center for Deliberative Democracy (September 2012). The National Deliberative Poll in Japan, August 4–5, 2012 on Energy and Environmental Policy Options.

1Ulaanbaatar city had 1,363,000 residents as of 2014 (National Statistical Office of Mongolia, 2015).

2Before the event, Professor James Fishkin of Stanford University delivered a day of training to all moderators. Moderators were trained not to give any hint of their own opinions. Their role was simply to facilitate an equal, mutually respectful discussion of the pros and cons of the various proposals.

3The final results provide a ranking of priorities from 0 (extremely undesirable) to 10 (extremely desirable), with 5 being exactly in the middle.