The box office success of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer suggests a strong public interest in the narrativization of scientific and political history. For Elham Hosseini (University of the Western Cape, 2019–20), it reconfirmed the effectiveness of cinematic techniques used in an Iranian film detailing the adverse impact of the Iran nuclear sanctions on the lives of ordinary citizens. This article is adapted from a longer paper written with Miki Flockemann, an extraordinary professor at UWC and Hosseini’s academic supervisor.

* * *

All Alone: The Messenger of Peace is a 2013 Iranian film by Ehsan Abdipour about a boy living near the Bushehr nuclear power plant whose friendship with the son of a Russian engineer is forced to end as the result of the nuclear sanctions against Iran. The film tangibly illustrates the impact of international sanctions on the lives of individuals through the lens of children and highlights perspectives often not directly addressed in the adult world, as the liminal position of preadolescents provides new space for exploring the unacknowledged effects of the sanctions.

On a personal level, the 2023 release of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer triggered in me—an Iranian who closely followed the nuclear talks between 2013 and 2015—immediate recollections of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), known more commonly as the Iran Nuclear Deal. In particular, the questions J. Robert Oppenheimer grappled with as a youth about the nature of the universe struck me as paralleling the dilemma faced by the young protagonist in All Alone. In the following, I will examine some of arguments advanced by Iran at the time All Alone was made in the light of new questions raised by Oppenheimer.

Illusion of Control

The connections between Oppenheimer and Iran’s negotiating team need to be clarified at the outset. Obviously, Oppenheimer’s mission to develop the most potent means of mass destruction the world had ever known is distinctively different from the attempts by Iranian negotiators, who included scientists and political representatives, to define the limits of the country’s nuclear program. Yet, one thing they had in common was the illusion of control—either over the results of their research or the outcome of the negotiations—a slippery slope when political interests are involved.

After the atomic bombing of Japan, Oppenheimer experienced a crisis of conscience and tried to warn American politicians against further nuclear development. He was met with hostility from rivals like Lewis Stauss, who supported nuclear development, as described in the Pulitzer prize-winning biography, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J Robert Oppenheimer: “Oppenheimer gave us atomic fire. But then, when he tried to control it, when he sought to make us aware of its terrible dangers, the powers that-be, like Zeus, rose up in anger to punish him” (Bird and Sherwin 2005, 15).

Iran’s second negotiating team, headed by a former foreign minister, meanwhile, made a successful attempt to break the international consensus against Iran by pledging a transparent nuclear program in return for revoking the threat of UN resolutions and the lifting of sanctions. However, the negotiators faced two serious obstacles: one was the presidency of Donald Trump, who ignored almost every international agreement between the US and the world—JCPOA being one of them—and the second was the position of hardliners in Iran, who scorned the team’s apparent naivety in believing what they saw as US false promises and urged the withdrawal from the deal as an act of retaliation—which did not, however, happen.

In this regard, the rise and fall of Oppenheimer, an expert in a specialized field of theoretical physics to whom the US government turned during a time of crisis, can be said to resemble the fate of the Iranian representatives tasked with breaking the impasse in the nuclear negotiations, in that both Oppenheimer and the Iranian team were subjected to false accusations despite having achieved what they were instructed to do.

The Figure of the Child in Iranian Cinema

Child-centered cinema has been a defining characteristic of neorealist filmmaking from the outset. As Deborah Martin (2019, 15) notes, these features typically include “a focus on the poor and working classes, a concern with social inequality, the use of natural actors and on-location shooting.” This aligns with All Alone, as Ranjero, the protagonist, and his young friends have to work to supplement the family income (although he is depicted doing so in a cheerful, entrepreneurial spirit, rather than as a victim of poverty). Shooting the film on location in Bushehr put this remote area of Iran and the struggles faced by the marginalized communities there in the spotlight. And while the youth playing Ranjero was not a “natural” actor, many of the other children in the film were nonprofessional, contributing to a sense of authenticity.

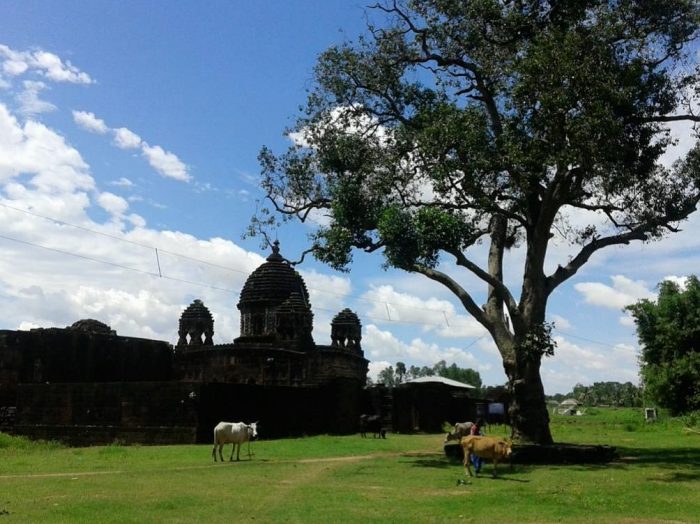

Two Iranian boys walk along a beach near the Bushehr nuclear power plant in a coastal village on the northern coast of the Persian Gulf. Bushehr is Iran’s first and only active nuclear power plant and was fully operational and connected to the national electricity grid in 2011 after a long history of construction delays and political challenges. ©Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Martin notes, “where filmmakers wish to denounce injustice or wrong, the child’s gaze is particularly useful, since cinema ‘tends to project into the child a certain ideal of visual neutrality’” (Sophie Dufays, quoted in Martin 2019, 15). What is interesting in the case of All Alone is that the film interjects three scenes from an adult perspective at strategic points in the cinematic narrative to unsettle the “visual neutrality.”

Drawing on Hamid Reza Sadr’s (2002) comments about how depictions of children in the post-revolution cinema of Iran contribute to exposing lived social realities, Anne Patrick Major (2012, 25) notes, “children in Iranian post-revolutionary cinema function empathetically, and by relating to individuals in a way that bypasses national and social belongings, children become a device to produce intercultural meanings.” While this comment refers to the way the spectators empathize with the characters and are thus affectively drawn into the narrative, the “intercultural meaning” generated is also manifested by the way Ranjero and the Russian boy, Oleg, interact with one another despite language barriers.

Major adds, “Sadr goes on to explain that children’s ‘personal troubles tend not to remain personal,’ which implies their existence in the world anterior to a given film is more realistic,” and this is borne out by Ranjero’s incarceration on an Italian ship. The perspectives outlined here thus clarify how “children allow for humanistic empathy despite the presence of national or cultural signifiers that could produce political and ideological readings if inscribed upon an adult,” which can then explain why the effects of nuclear sanctions in Iran are more compellingly presented via a child-centered narrative.

Emmanuel Levinas’ ideas on ethics presented in Totality and Infinity questions the traditional Greek/European notions based on the “ego as the self-conscious knowing subject” (Levinas, quoted in Nojoumian and Nojoumian 2020, 200). Instead, Levinas proposes an ethical system that puts in question the subject’s own ego and as a result is essentially characterized by the other: “one is in a face-to-face relationship with the other, with infinite responsibility” (quoted in Nojoumian and Nojoumian).

Accordingly, the traditional notions of “self,” which ultimately nurture an egotistical subject, are replaced by a concept in which the self is not only defined by and dependent of but also responsible for the other in their very recognition or being. Attempting to further clarify this responsibility, Amir Ali and Amir Hadi Nojoumian explain that children do not feel responsible toward the other out of reciprocity but essentially as the “self’s obligation” (2020, 200), which sees the other as part of the self, thus enabling a relationship between two boys who do not speak each other’s language.

Making the Unseen Visible

What follows is a close analysis of the film All Alone, which helps clarify how children’s portrayal in fiction and film narratives can move beyond stereotypical assumptions and raise questions about the issues that adults find so difficult to approach. There are certain factors that help All Alone express the genuine feelings of children while also engaging effectively with the world of adults, that is, the nuclear negotiations and sanctions. The first is Ranjero’s age: he is an adolescent, about to step into adulthood but still very much in touch with childlike emotions, which puts him in an “in between” position throughout the film.

The second is the character of Olga, one of the engineers working at the Bushehr plant, who becomes the translator between the Oleg and Ranjero and a facilitator of their relationship. In her role as an interpreter of the events of Ranjero’s life to the captain of the ship in Italy where Ranjero was kept in custody as a stowaway, we too are being informed. Yet, as noted by Sadr, because of the affective identification with the child protagonist in a child-centered film, the viewer responds empathetically (like Olga) to the “intercultural meanings” (quoted in Major 2012, 25) of the worldview of Ranjero and Oleg.

Ranjero’s questions about the nuclear talks can be used to address a range of concepts from a child’s perspective. For instance, in “Visible Man or the Culture of Film” (2010), Béla Balzás makes a connection between a child’s point of view and “the secret corners of a room” (quoted in Han and Singer 2021, 4) that are exposed so that the often unseen becomes visible and open to question through the eyes of a child.

In her 1995 novel Ten Is the Age of Darkness, Geta Leseur uses a poignant metaphor to describe the child’s viewpoint as a “forgotten camera in the corner” (quoted in Flockemann 2005, 117), whose presence may not be felt but fulfills its function to observe and record and, in the process, offers an unconscious critique of the adult world (Flockemann 2005, 117). In a much broader sense, Negar Mottahedeh (2005, 342) draws on Sadr to offer a reading of the child figure in Iranian cinematography as an allegory of the restrictions faced by the film industry: “The child can embody spatial positions and emotional states that other filmic characters cannot. The figure of the child, then, allegorically foregrounds the constraints of the film industry under state-guided dictates.”

Challenging the Viewer

Ranjero’s role in the film is to serve as a liminal agent, moving between the children’s and adult worlds to raise new ethical questions regarding Iran’s nuclear program and the controversies surrounding it. His dreams, at the beginning and end of the film, parallel the troubled worldview of the youthful Oppenheimer, which is intriguing in that the physicist’s research can be seen as one source of Ranjero’s anguish. Like the young Oppenheimer, Ranjero is distraught, being stuck on a ship and homesick and crying aloud in his sleep for Heleylah, his hometown. An emotionally immature Ranjero is troubled by visions of a “hidden universe” that he thought he could understand.

What is troubling both Ranjero and Oppenheimer is an apprehension of what is to become of the adult world that, for Ranjero, constitutes “nightmares.” At the end of All Alone we are left with an unanswered question, namely, will Ranjero find a way to overcome the nightmares he has about the future and realize the sweet dreams he hopes for? The open-ended conclusion is deliberately unsettling because Ranjero’s question, posed as a child, offers a challenge to the grown-up viewer.

References

All Alone: The Messenger of Peace. Directed by Ehan Abdipour, Edris Abdipour (Studio), 2013.

Bird, Kai, and Martin J. Sherwin. American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robbert Oppenheimer. Vintage Books, 2005.

Bushati, Angela. “Children and Cinema: Moving Images of Childhood.” European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2018, pp. 34–39.

Flockemann, Miki. “Mirrors and Windows: Re-Reading South African Girlhoods as Strategies of Selfhood.” Counterpoints, Vol. 245, 2005, pp. 117–32. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42978695.

Han, Yunzi, and Christine Singer. “Transformational Identities of Children within Iranian and South African Fiction Films: Ayneh (The Mirror) and Life Above All.” Open Screens, Vol. 4(1), No. 5, 2021 pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.16995/os.40.

Major, Anne Patrick. “Bahman Ghobadi’s Hyphenated Cinema: An Analysis of Hybrid Authorial Strategies and Cinematic Aesthetics.” Master’s thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 2012. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/f1475305-fd95-4a29-adc2-3c2c02812b3c.

Martin, Deborah. The Child in Contemporary Latin American Cinema. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/978-1-137-52822-3.

Mottahedeh, Negar. Review of Richard Tapper, ed., The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation, and Identity. Iranian Studies, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2005, pp. 341–44. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4311731.

Nojoumian, Amir Ali, and Amir Hadi Nojoumian. “Towards a Poetics of Childhood in Abbas Kiarostami’s Cinema.” In Bernard Wilson and Sharmani Patricia Gabriel, eds., Asian Children’s Literature and Film in a Global Age: Local, National, and Transnational Trajectories. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, pp. 195-211, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-15-2631-2_10.

Sadr, Hamid Reza. “Children in Contemporary Iranian Cinema: When We Were Children.” In R. Tapper, ed., The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity. I.B. Taurus Publishing, 2002.