Yance Arizona[1] is a 2011 Sylff fellow from the University of Indonesia and currently a PhD candidate at Leiden University in the Netherlands. Using an SRA award, he visited the Osaka University of Tourism in Japan and the University of New South Wales in Australia to sharpen the comparative elements of his research on customary land recognition in Indonesia. In this article, he focuses on lessons learned about the resilience of common forest management in Japan by discussing the challenges and innovations of state and nonstate actors.

* * *

Community-based forest management has a long history in rural Japan. Since the Edo period (1603–1868), rural communities have shared their collective land and labor to maintain forest and other natural resources for self-sufficiency. This model of natural resource practice is known as common forest management. The common forest, called iriai in Japanese, became integrated into the traditional village system.[2] The membership of iriai common forest groups is embedded in that of traditional Japanese villages (mura). However, common forest management has slowly changed over time due to internal and external factors since Japan entered the industrial revolution. This article discusses several challenges concerning the current practice of common forest management in Japan. I also reveal several initiatives by the government and citizens to restore collaborative forest management and to renew interest in rural development. The analysis in this article is based on interviews, literature studies, and observations conducted in two rural areas in Japan during my Sylff Research Abroad (SRA) fellowship in November and December 2019.

What Is the Common Forest in Japan?

Many scholars have used the iriai forest or common forest in Japan as an illustrative example of potential community-based management as an alternative to private property ownership and an extractive model of natural resource management (Mitsumata and Murata 2007; Berge and McKean 2015). For a long time, the rural population in Japan has collectively engaged in agricultural activities in shared communal land by planting trees, especially sugi and pine, to meet their daily needs. Iriai groups have collectively cleared, planted, maintained, and harvested forest products to provide mutual benefits among the members. The membership of the common forest group was initially based on the membership of a village. Since the Japanese government installed modern development programs, primarily through the Meiji Restoration (1868), many traditional concepts, laws, and activities have slightly changed. In the following section, I will discuss five concerns about recent developments in common forest management in Japan.

Five Challenges of Common Forest Management

The common forest practice in Japan faces multidimensional challenges. Here I will briefly discuss five major challenges of the common forest in Japan, including demographic, economic, environmental, institutional, and regulatory factors.[3] Firstly, legal uncertainty leads to misrecognition and disputes among iriai rights holders (regulatory factor). During the Meiji era (1868–1912), Japan’s Civil Code began to take effect. The Civil Code is a mark that Japan began incorporating a modern legal system inspired by the German and French legal traditions (Kanamori, 1999). Regarding the property right regime, the modern Civil Code strictly divides land property into private and public properties (Suzuki, 2013: 67–86). In short, private property is in the ownership of individual citizens, whereas public property belongs to the state or other public bodies. This dichotomy leads to uncertainty regarding the legal status of iriai forests because the iriai model cannot be categorized as either private or public property. As a result, Article 263 of the Civil Code considers the common forest to be in the co-ownership of a group of citizens. By contrast, Article 294 stipulates iriai as the right of the local population to use state land or forest. Neither of these articles represents the original model of iriai forest rights, which combine communal and individual land ownership.

Misrecognition of the legal status of the common forest in the Civil Code generates ambiguity in land registration practices. Iriai rights holders have to register their common land and forest under “nominal names” on behalf of other legal entities. Gakuto Takumura (2019) demonstrates six models of how iriai rights holders register their communal land rights. These six models of adaptation to the modern land administration system appear in the registration of a common forest on behalf of other legal entities, such as (a) a leader of a village, (b) several leaders of a village, (c) all household heads in a village, (d) a shrine or temple of a village, (e) a new municipality, or (f) a district, a cooperative, or an authorized community association. Registering the iriai right under nominal names has occasionally caused legal disputes among the iriai rights holders. One case that received much attention in Japan was the Kotsunagi case, which took decades for the courts to settle (Inoue and Shivakoti 2015).

The author gives a guest lecture on customary forests and tourism in Japan and Indonesia at the Osaka University of Tourism. Detailed information can be found at https://www.tourism.ac.jp/news/cat3/5810.html.

The second concern is government imposition of the modernization of iriai forest management (institutional factor). Besides the legal status, another institutional challenge to the iriai forest is the modernization of the rural administrative system. In the early period of the Meiji era, the Japanese government announced a policy to modernize village governments. The modernization of village government affects iriai forest management because iriai group membership was traditionally based on membership in a traditional Japanese village. This challenge parallels the general trend in rural Japan to merge villages rather than splitting them into several smaller villages. When two or more villages are merged, a question arises regarding the ownership and membership of iriai rights, whether it still belongs to the initial village that has merged or it becomes the co-ownership of the new village union.

Another striking policy by the Japanese government to modernize iriai forest management is the Modernization of the Common Forest Act of 1966 (Takahashi and Matsushita 2015). This act intended to transform traditional common forest practices into modern forest management. However, the implementation of this act did not result in a uniform model of forest management; instead, the act has been adopted in different models of forest management depending on the social conditions of iriai rights holders. Research by Daisaku Shimada (2014) revealed how rural communities in the Yamaguni district in Kyoto adapted to the Modernization of Common Forest Act and other external influences, such as population change and the timber liberalization policy in securing common forest management. Rural communities modify their common forest institution to allow migrants to be members of new forest management boards.

The third challenge is depopulation and urbanization (demographic factor). In contemporary Japan, depopulation and urbanization are central issues in the debate on rural development. Japanese society is experiencing depopulation because of a low birthrate and an aging population. At the same time, the urbanization level is dramatically high. Many young people move away to live in urban areas, leaving the rural areas mainly inhabited by older generations. Depopulation and urbanization affect the membership and decision-making process in common forest management. The membership of iriai forest groups shrinks as some of the members move to the city or elsewhere, causing a reduction of the workforce in the management of the common forest. In the past, iriai rights holders lived permanently in a village. When someone moved to other villages, his or her rights to the iriai forest vanished. Today, some people consider their rights to remain valid even when they have moved to other villages. Another problem in terms of people’s mobility concerns the decision-making process in common forest management. Traditionally, iriai rights holders decide on common forest management through a consensual agreement among the group members (Goto 2007). If a member of the iriai group is not involved or disagrees with the majority opinion, it means that the group has not reached a consensual decision. Currently, some iriai groups apply flexible categorization to their common forest membership by including newcomers to the board and involving them in the decision-making process. The lack of a clear decision-making process and a shrinking workforce have led to the underuse of iriai forests in several places in rural Japan.

The fourth problem is the timber liberalization policy (economic factor). In the 1960s, the Japanese government introduced a timber trade liberalization policy to support industrial development. This policy increased timber import from other countries, mainly from the United States, Russia, and Southeast Asian countries. As a result, this strategy decreased the competitiveness of domestic timber production and the economic value of wood, which has been the core commodity of common forests. Before the timber liberalization policy, the common forest supplied wood for building houses, offices, castles, and temples, as well as for making furniture, and provided firewood for cooking and heating. From the 1960s onward, as the country entered a period of rapid economic growth, Japan replaced the use of wood with other resources. The use of concrete and steel is more dominant for residential buildings and offices, and the use of fossil fuels in place of firewood is increasingly widespread. In addition, to meet domestic wood demand, the Japanese government no longer relies on domestic supplies and relies instead on imported wood. This timber import policy devastated Japan’s domestic timber production and market. Consequently, the core business of iriai forests, that of meeting domestic wood demand, has gradually declined. Lack of productive activities in rural areas also became one of the drivers for rural people to move to big cities.

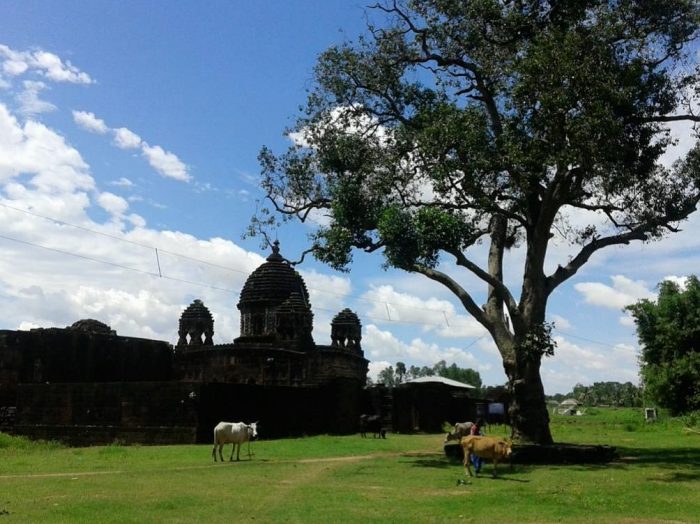

Together with a group of postgraduate students from Kyoto University, the author visits a private forest in Kawakami Mura, Nara Prefecture. This forest site is the oldest planted forest in Japan.

The final concern relates to land degradation (environmental factor). Iriai rights holders maintain the common forest by growing supporting plants around the main trees. These plants support soil fertility and provide economic benefits to farmers. However, due to the shortage of labor to maintain the common forest, conifer plantations are left unmaintained. At first glance, this condition looks good for conservation, because forests are left green and trees grow for long periods. But apparently, this is not suitable for the healthy growth of the main trees because they are in competition with the shrubbery. Moreover, unmanaged conifer plantations cause frequent landslides in rural areas. These disasters are compounded by the typhoon and earthquake catastrophes that often occur in Japan. This environmental vulnerability is not only the cause but also the result of underutilization of the common forests.

Revitalization Movements

The revitalization of common forest management in Japan corresponds with an attempt to improve rural livelihoods. The Japanese government and nongovernmental organizations engage in rural development, including the revival of common forest management. The Japanese government, through the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, implements a program to increase the interest of urban residents, either Japanese citizens or immigrants, in living in rural areas. These people from different locations assist rural community members in meeting their basic needs, especially related to health and livelihood. Moreover, the Japanese government promotes a “forest volunteer program” to attract people’s interest in getting involved in forest restoration activities. Forest volunteers are individuals other than forest owners or those with a direct interest, who participate in on-site work necessary for forest management in response to the critical state of the forests. Shinji Yamamoto (2003) found that the forest volunteer program has been generating a positive impact on drawing urban people’s interest in forestry activities. This program began in the 1970s and has since spread across the country. According to Japan’s Forestry Agency, the number of citizens’ organisations that have participated in forest volunteer activities was 2,677 as of 2010 (Yamamoto 2003).

Nonprofit organizations and universities also run several programs to enhance the interest of young generations regarding rural livelihood and environmental management. A crucial example is the kikigaki program. Literally, kikigaki consists of the words kiki (“listening”) and gaki (“writing”). The kikigaki program encourages young people to take an interest in the stories of local people. Kikigaki is a learning method for understanding someone’s life story through direct dialogue. Since 2002, high schools in Japan have adopted the kikigaki method to raise students’ awareness of societal problems faced by rural communities (Effendi 2019). Due to the increase in global attention toward environmental issues, the kikigaki program also covers environmental education for children. Environmental issues allow students to get involved in the revitalization of common forest management. The kikigaki program initially developed in Japan and spread out to other countries, such as Indonesia. I interviewed Motoko Shimagami, who is developing kikigaki programs in both Japan and Indonesia. According to Shimagami, youth involvement is an essential factor in improving rural livelihood and sustainable environmental management. Several years ago, Shimagami conducted a comparative study of common forest management between Indonesia and Japan (Shimagami 2009) and found that similar methods of revitalization of the common forest through the education of high school students are pivotal in both countries.

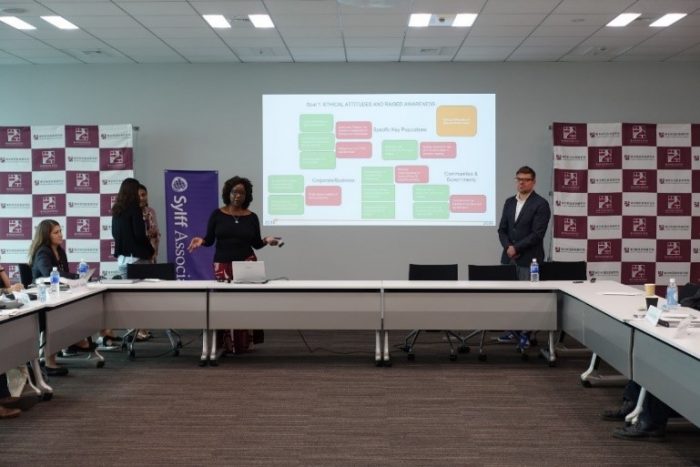

Matsutake Crusaders, a voluntary group dominated by elders who gather every week to maintain a hill landscape, creating a suitable condition for matsutake mushrooms to grow.

Another initiative that I have seen in Japan is the ecovillage network. An ecovillage is an intentional, traditional, or urban community that is consciously designed through locally owned participatory processes encompassing social, cultural, ecological, and economic dimensions to regenerate social and natural environments.[4] In 2013, I visited the Konohana Family ecovillage in Shizuoka Prefecture. This ecovillage is part of a worldwide ecovillage network. The Konohana Family, though it calls itself a family, consists of 100 members who are not of the same blood. They live in rural areas and cultivate collective agricultural land. With the spirit of “togetherness” as a family, they fulfill basic needs through collective land management. During my visit to Japan with the support of the SRA fellowship program, I visited the Matsutake Crusaders in the northern part of Kyoto. This group consists of more than 30 retirees who gather once a week to engage in collaborative natural resource management. They nurture matsutake, a wild mushroom typical of Japan that has high economic and cultural values (Tsing 2015). They voluntarily cut some pine wood as a precondition to creating a suitable environment for matsutake to grow. Professor Fumihiko Yoshimura, the leader of this group, said that although this initiative is different from the iriai rights model, they called it a satoyama movement. The satoyama concept in landscape management combines forest and agricultural activities, mainly in hill areas. Currently, many rural communities in Japan are involved in satoyama movements (Satsuka 2014). In another location, a study by Haruo Saito and Gaku Mitsumata (2008) shows the integration of matsutake production with traditional iriai land use in Oka Village, Kyoto Prefecture.

This article has illustrated five major challenges of common forest management in Japan. These challenges are responded to with a variety of innovations by the government and nongovernment organizations to help the common forest practices survive in supporting rural livelihood. These innovations to revitalize community-based natural resource management have been developed with various narratives such as environmental movements, rural livelihood supports, family and community orientation projects, and voluntary civic education. Although rural communities have encountered serious challenges since Japan entered industrial development, villagers continue to maintain the common forest with some modifications. Villagers demonstrate the resilience of common forest management by taking an inclusive approach that includes migrants in the board membership of common forest management and by involving themselves in broader networks of community-based natural resource movements. Community resilience is the crucial factor in common forest management in Japan.

References

Berge, Erling, and Margaret Mckean. 2015. “On the Commons of Developed Industrialized Countries.” International Journal of the Commons 9, no. 2 (September 2015): 469–85.

Effendi, Tonny Dian. 2019. “Local Wisdom-based Environmental Education through Kikigaki Method: Japan Experience and Lesson for Indonesia.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 239: 012038. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/239/1/012038.

Goto, Kokki. 2007. “‘Iriai Forests Have Sustained the Livelihood and Autonomy of Villagers’: Experience of Commons in Ishimushiro Hamlet in Northeastern Japan.” Working Paper Series No. 30. Afrasian Centre for Peace and Development Studies, Ryukoku University.

Inoue, Makoto, and Ganesha P. Shivakoti. 2015. Multi-level Forest Governance in Asia: Concepts, Challenges and the Way Forward. India: Sage Publication.

Kanamori, Shigenari. 1999. “German Influences on Japanese Pre-War Constitution and Civil Code.” European Journal of Law and Economics 7, no. 93–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008688209052.

Mitsumata, Gaku, and Takeshi Murata. 2007. “Overview and Current Status of the Iriai (Commons) System in the Three Regions of Japan: From the Edo Era through the Beginning of the 21st Century.” Discussion Paper No. 07-04. Kyoto: Multilevel Environmental Governance for Sustainable Development Project.

Miyanaga, Kentaro, and Daisaku Shimada. 2018. “‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ by Underuse: Toward a Conceptual Framework Based on Ecosystem Services and Satoyama Perspective.” International Journal of the Commons 12, no. 1: 332–51.

Saito, Haruo, and Gaku Mitsumata. 2008. “Bidding Customs and Habitat Improvement for Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake) in Japan.” Economic Botany 62, no. 3: 257–68.

Satsuka, Shiho. 2014. “The Satoyama Movement: Envisioning Multispecies Commons in Postindustrial Japan.” In Asian Environments: Connections across Borders, Landscapes, and Times, RCC Perspectives, no. 3: 87–94.

Shimagami, Motoko. 2009. “An Iriai Interchange Linking Japan and Indonesia: An Experiment in Interactive Learning and Action Leading toward Community-Based Forest Management.” Working Paper Series No. 46. Afrasian Centre for Peace and Development Studies, Ryukoku University.

Suzuki, Tatsuya. 2013 “The Custom and Legal Theory of Iriai in Japan: A History of the Discourse on the Position of the Rights of Common in the Modern Legal System.” In Local Commons and Democratic Environmental Governance, edited by Takeshi Murota and Ken Takeshita. Tokyo-New York-Paris: United Nations University Press.

Takahashi, Takuya, and Koji Matsushita. 2015. “How Did Policy Intervention Work Out for Commons Forests in Japan? An Analysis of Time-Series Prefectural Data.” Paper in the IASC Conference 2015 Edmonton W23 (2015-5-27).

Takamura, Gakuto. 2019. “The Bundle of Rights Model to Explain the Underuse of Japanese Common Forest from History.” Presentation in Asian Law and Society Association (ALSA) Conference, Osaka Univesity, December 12–15, 2019.

Tsing, Anna L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruin. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Yamamoto, Shinji. 2003. “Forest Volunteer Activity in Japan.” In Local Commons and Democratic Environmental Governance, edited by Takeshi Murota and Ken Takeshita. Tokyo–New York–Paris: United Nations University Press. 287–302.

[1] I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Sozaburo Mitamayama (Osaka University of Tourism) for his hospitality and assistance during my research visit in Japan. I am also thankful for a series of insightful discussions that I have had with Motoko Shimagami (Ehime University), Gaku Mitsumata (Hyogo University), Gakuto Takamura (Ritsumeikan University), and Mamoru Kanzaki and Daisuke Naito (Kyoto University), and for the fruitful comments by Hoko Horri (Leiden University) for this article.

[2] In this article, the terms “common forest” and “iriai forest” are used interchangeably.

[3] See also Kentaro Miyanaga and Daisaku Shimada (2018), who identify three main driving factors that lead to the underuse of common forests in Japan: demographic drivers, socioeconomic drivers, and institutional drivers.

[4] See. https://ecovillage.org/projects/what-is-an-ecovillage/