SRG 2024–supported research led by Obby Taufik Hidayat (Universiti Malaya, 2023) examined the first pillar of the Golden Indonesia 2045 vision, proposing the adoption of service learning as an innovative pedagogy to strengthen students’ knowledge, skills, and character.

* * *

Education is widely recognized as a fundamental factor in developing well-rounded individuals. Indonesia’s aspiration to become a leading nation across various sectors by the centennial of its independence in 2045—as outlined in its Golden Indonesia 2045 vision—rests on equipping individuals to tackle diverse challenges. According to economic data from the Ministry of Education and Culture, Indonesia is projected to benefit from a demographic bonus, providing an ample source of human capital for development. Between 2030 and 2045, approximately 70% of the population is expected to be of productive age (15–64) (Irfani et al. 2021). Educational transformation will thus be essential for developing intelligent and principled citizens to achieve the vision’s goals.

In 2020, the ministry introduced the Merdeka Belajar Kampus Merdeka (MBKM), or Freedom of Learning and Independent Campus, policy, which emphasizes experiential learning. One program that operationalizes this aspect of MBKM is Kuliah Kerja Nyata (KKN), or the Community Service Program. While KKN has often been identified as a service-learning initiative, its current implementation at Indonesian universities does not adequately incorporate the essential components of service learning, instead primarily emphasizing community service or volunteerism and often lacking integration with university courses or curricula (Hidayat and Balakrishnan, 2024). There has thus been reduced emphasis on student learning outcomes.

In contrast, service learning aims to enhance students’ mastery and understanding of theoretical knowledge acquired in the classroom by providing hands-on experience in community service projects and fostering meaningful reflection on these experiences. Strengthening the connection between academic content and community engagement can ensure that student learning is not only maintained but also enriched through service initiatives (Salam et al. 2019). Accordingly, this study aims to improve KKN by integrating service-learning principles to develop value-based graduates in a diverse environment.

A qualitative multiple-case study design was employed to explore the application of service learning within the KKN program. Data collection involved semi-structured interviews, observations, and document reviews involving two KKN groups: one following the usual approach and the other implementing service-learning elements introduced by the researcher. The researcher then compared the two groups, and the data were analyzed using content analysis and manual thematic analysis.

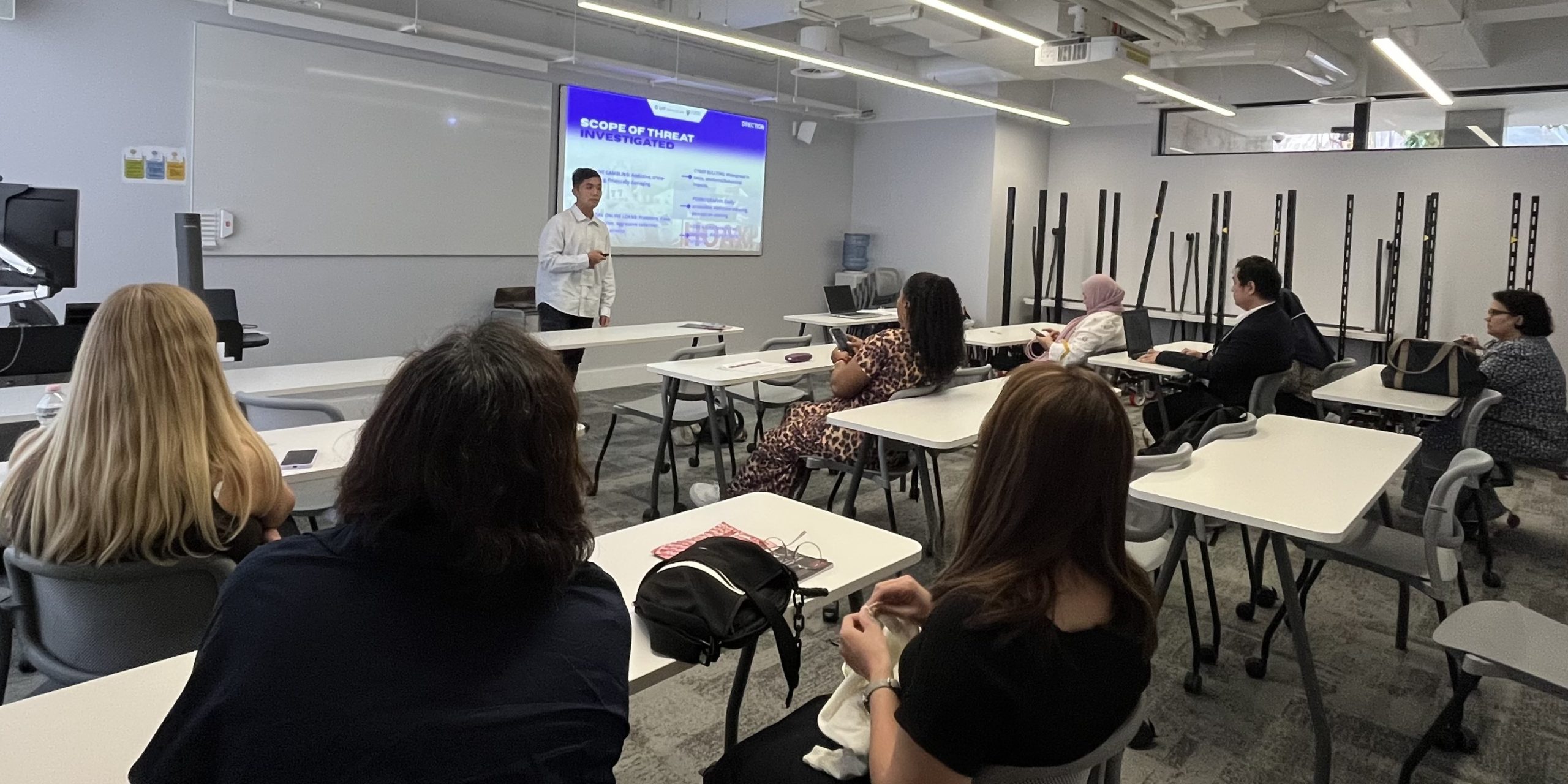

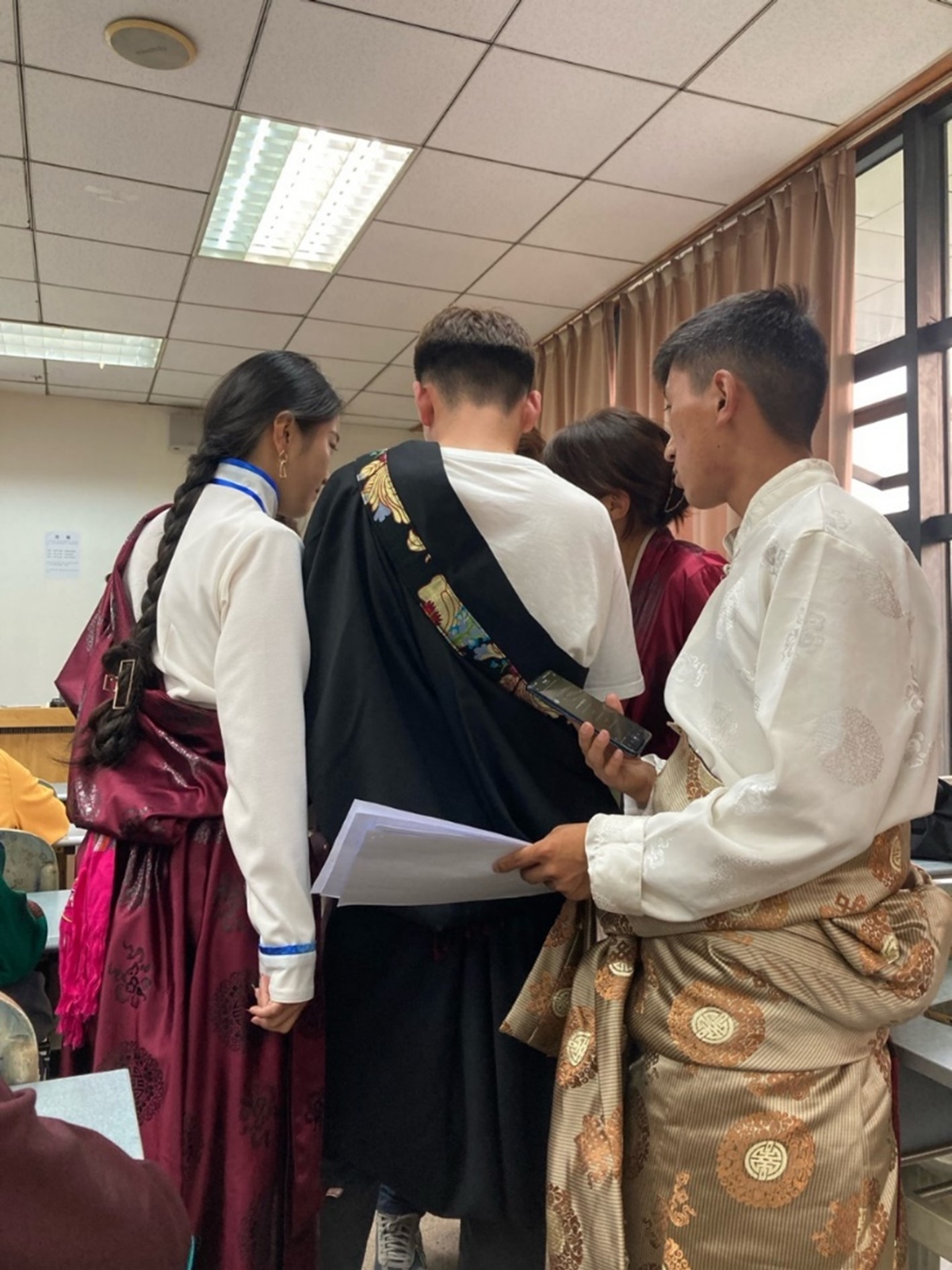

Semi-structured interviews and observations of participants in this research.

Furthermore, during data collection, given the limited research on service learning in Indonesia and the need to enhance international understanding, the researcher attended the 2024 IARSLCE Asian-Pacific Conference X International Conference on Service-Learning at Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) as both a presenter and participant in several workshops. This event represented a collaborative initiative among international associations dedicated to advancing service-learning research and promoting community engagement in the Asia Pacific region.

In addition, the workshop shown below was part of the preconference session at the international conference. During this event, the researcher gained new insights into service learning from several international experts in the field. These discussions helped broaden understanding of the philosophy, key elements, and objectives of service learning. They also facilitated comparative analysis of service learning across several countries, yielding new perspectives that have become a crucial part of service-learning research in Indonesian higher education.

The preconference workshop on Setting a Global Research Agenda for Service Learning at PolyU, Hong Kong.

Meaningful Experiences: Findings from Community Projects

Both the lecturer and students in this study reported that service learning, as an experiential approach, strengthens compulsory, community-service-based courses like KKN. Although KKN incorporates hands-on learning, service learning is seen as more structured and effective for integrating experiential learning in community service settings. This observation aligns with Tan and Soo (2020), who assert that academic experiential learning plays a key role in cultivating responsible citizenship. Therefore, service-learning programs are designed to deepen students’ understanding of theoretical concepts introduced in the classroom through practical application.

The findings of this study indicate that a defining characteristic of service learning is its emphasis on experiential learning, which integrates community-service activities with students’ prior classroom knowledge. This aligns with experiential learning theories advanced by several scholars. Dewey (1938) advocated for “learning by experience” and examined the broader role of academic institutions in community development. Kolb (1984) conceptualized experiential learning as a holistic process integrating observation, empowerment, reflection, experience, and action through behavioral development across diverse contexts.

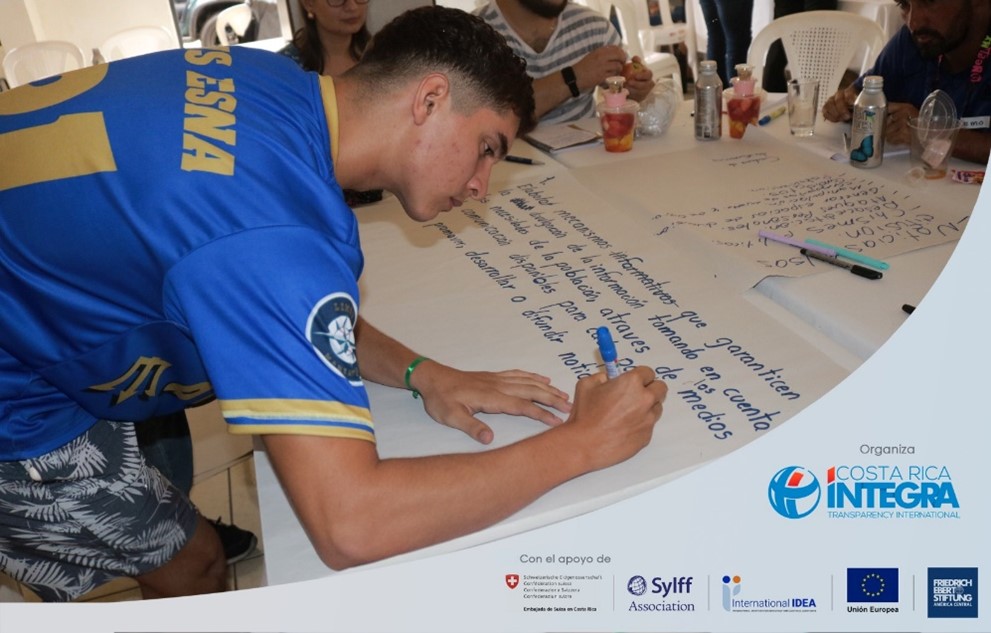

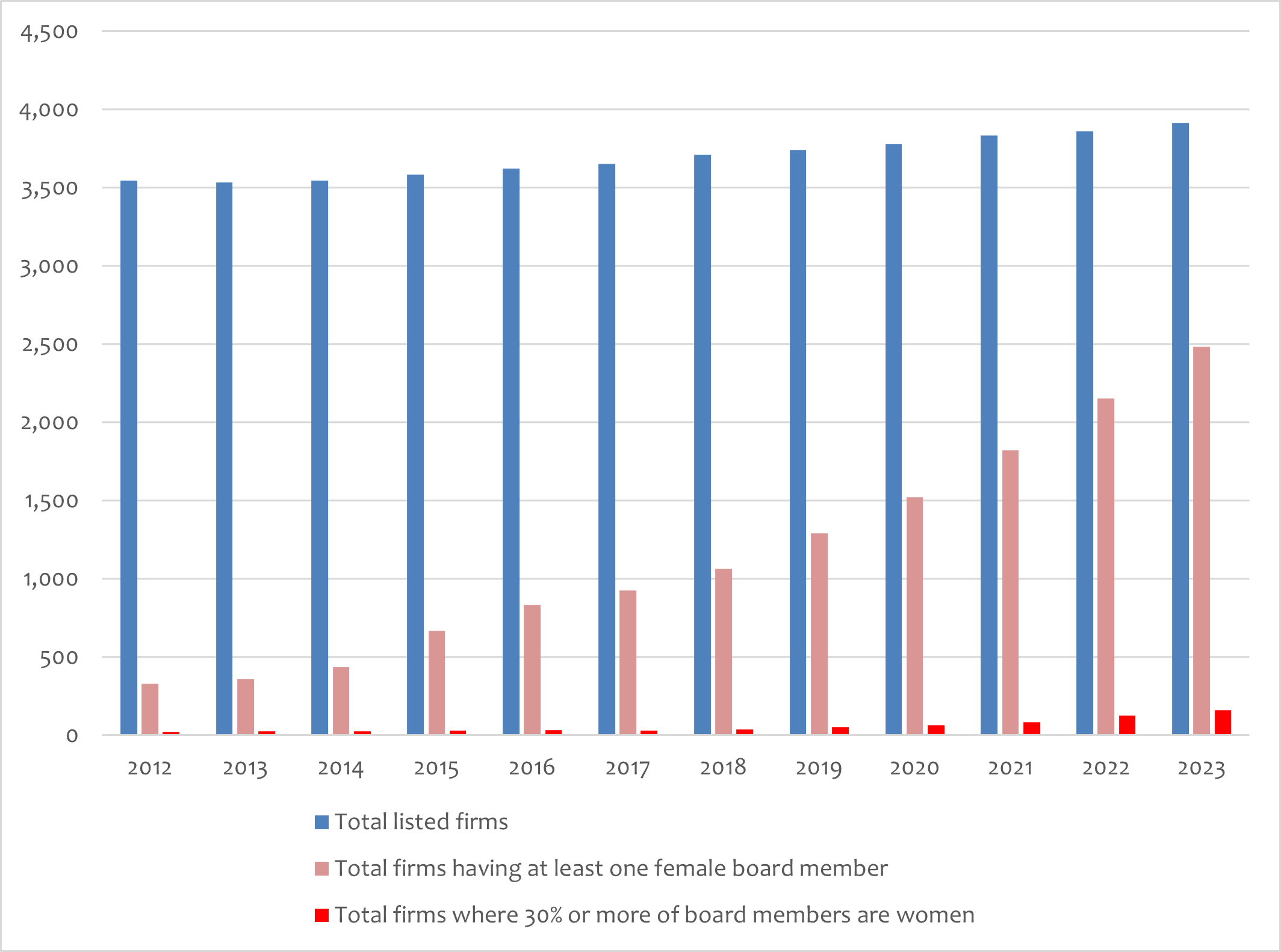

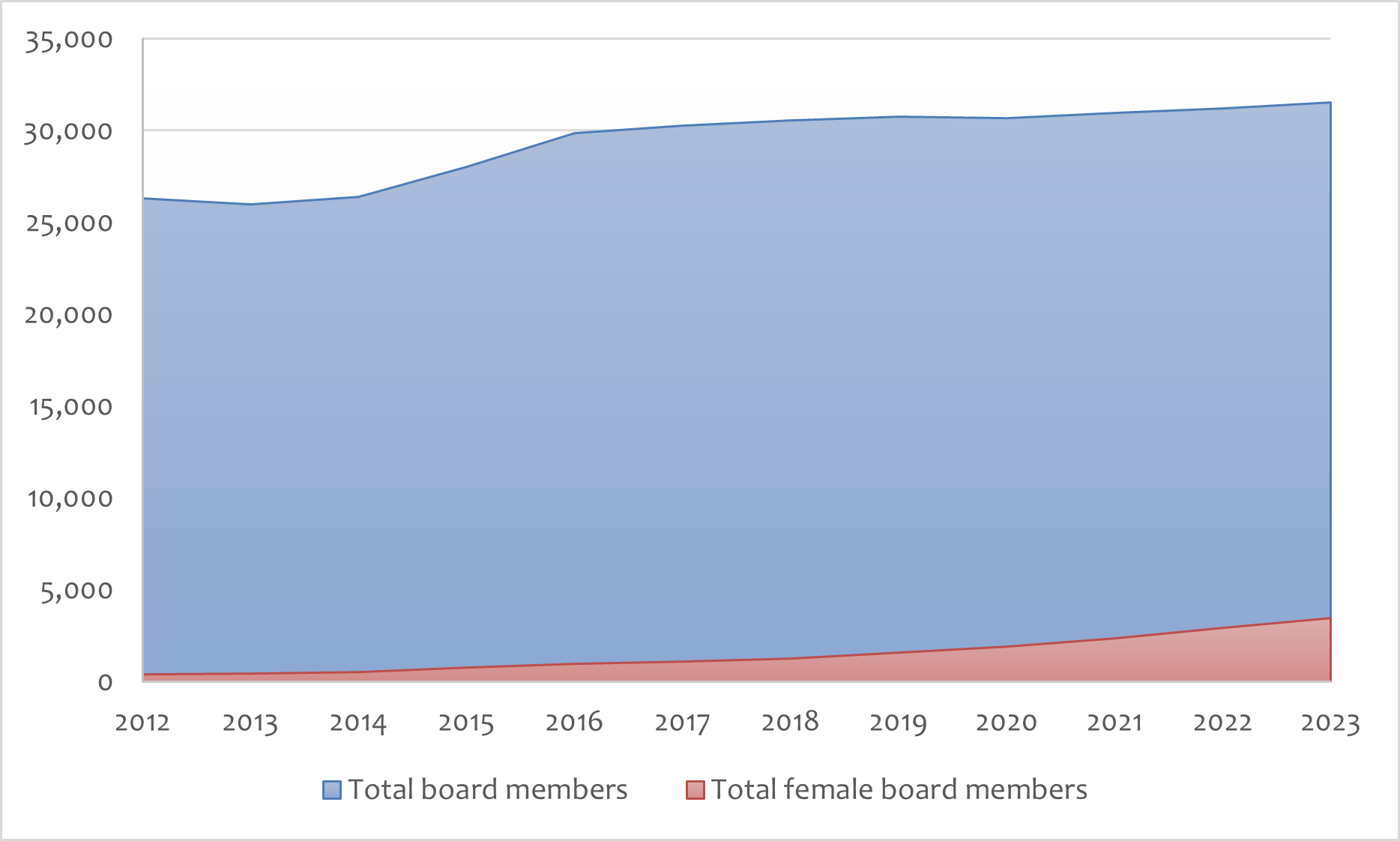

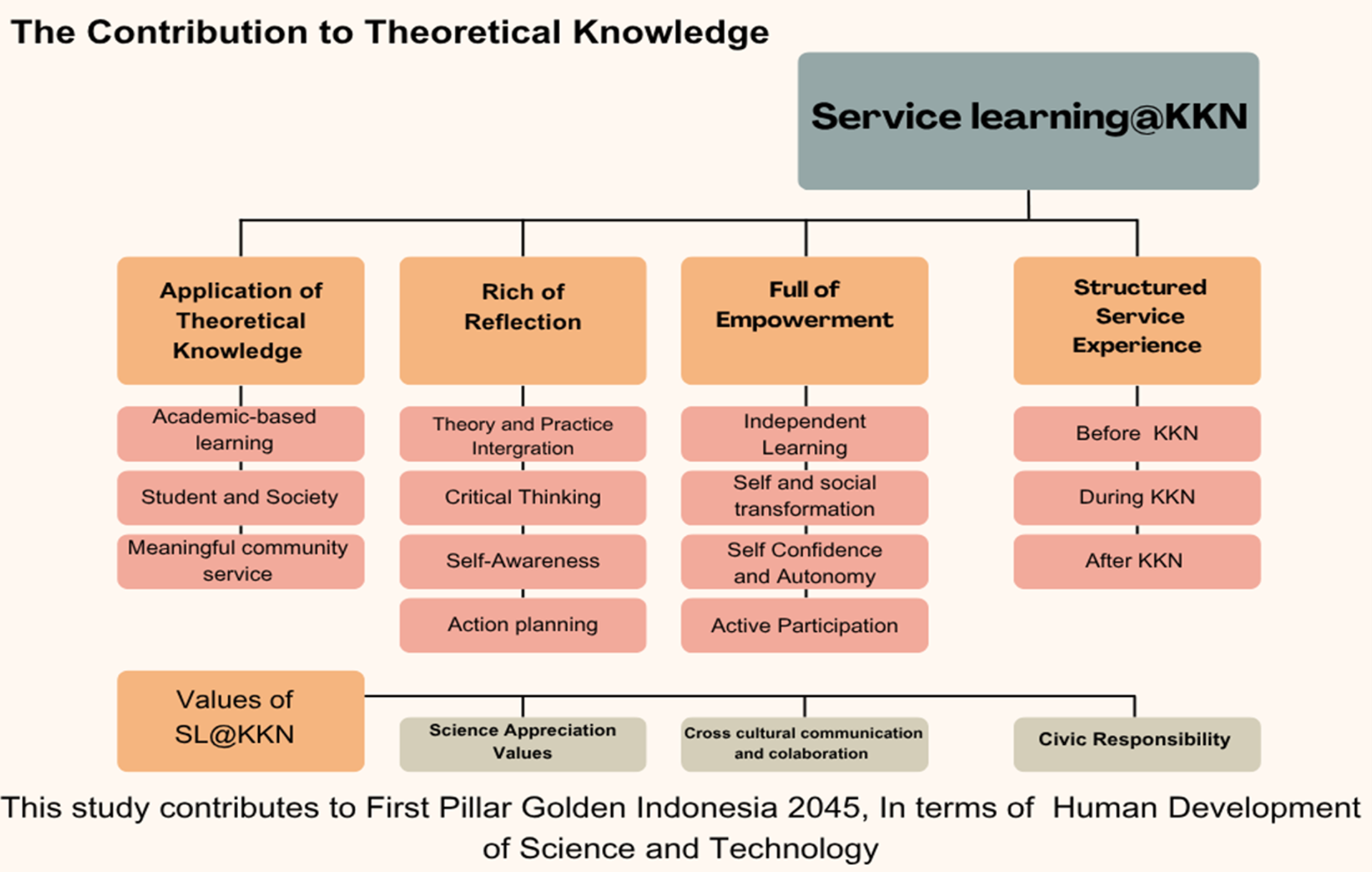

Kolb further defined experiential learning as a process of exploration and engagement that connects prior knowledge with new understanding, encouraging sharing, reflection, and cognitive processing. In the context of service learning in Indonesia (see figure below), learning is more effectively sustained through conceptual and process-oriented approaches, which sharpen critical thinking skills and enhance intrinsic motivation for discovery. Experiences that contribute positively to the learning process are considered valuable.

The characteristics of service learning in the KKN program begin with students identifying societal problems or issues they intend to address. Next, students engage directly and meaningfully with the community. In the third stage of experiential learning, they integrate their personal experiences with the theoretical knowledge acquired in the classroom. This process enables students to generate new knowledge by developing original ideas or concepts, which are then shared to address community challenges. In the final stage, students reflect on their societal experiences through critical and creative thinking. According to Hinchey (2004), students who reflect on their learning experiences become active learners, and those who engage in extensive reflection continue to expand their knowledge. Balakrishnan et al. (2022) noted that increased experiential engagement enhances students’ capacity for reflection, thereby facilitating the development and accumulation of knowledge, values, and skills.

Implications for Pedagogy and Policy

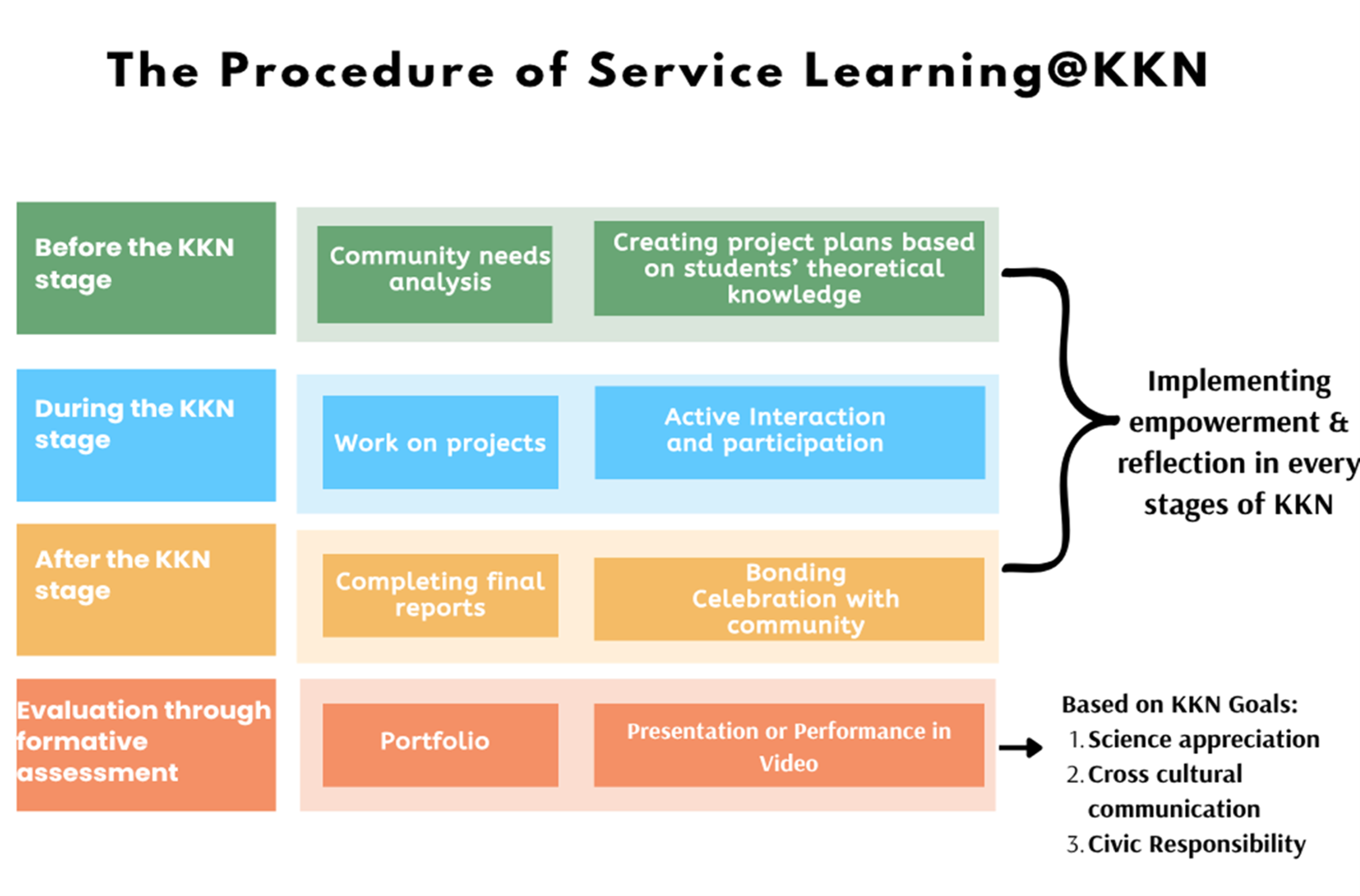

The findings of this study suggest procedures for improving KKN implementation in higher education, which could strengthen its role as a service-learning approach in Indonesia. Service learning encourages students to apply theoretical knowledge, values, and skills within real-world community contexts, thereby supporting and strengthening local communities. The figure below presents an overview of the study’s results and outlines a procedure for implementing service learning in Indonesia. This approach seeks to enhance KKN by transforming it into an innovative pedagogy that positively impacts both students and the community.

Service-learning pedagogy is essential because it provides a structured environment in which students can apply classroom knowledge to real community situations. Through direct engagement, students gain practical experience and insights. Their active participation encourages reflection and empowerment and enhances the learning process. By engaging in reflection, students reconstruct knowledge and deepen their understanding (Balakrishnan et al. 2022). In a multicultural society, such reflection plays a vital role in cultivating individuals who embody the core values of Pancasila—the five principles that form Indonesia’s foundational ideology—an attribute that will be critical for future graduates.

Therefore, it is crucial to recognize and integrate service learning into KKN programs. Specifically, these programs should incorporate hands-on community engagement, reflection activities, and collaborative problem-solving, consistent with the philosophy and principles of service learning. Findings from this study can provide a valuable reference for shaping educational policies in Indonesia. University rectors, deans, and lecturers can use these findings to help design policies that prioritize these elements. Such policies will elevate KKN to international standards of service learning.

Incorporating service learning into KKN programs will help produce graduates with strong academic qualifications who are well-prepared to contribute to a multicultural society. This effort matches the broader goal of transforming higher education and supports the realization of the first pillar of Golden Indonesia 2045: advancing human development and the progress of science and technology.

References

Balakrishnan, Vishalache, Yong Zulina Zubari, and Wendy Mei Tien Yee. 2022. Introduction to Service Learning in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press.

Dewey, John. 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Kappa Delta Pi.

Hidayat, Obby Taufik, and Vishalache Balakrishnan. 2024. “Service Learning in Higher Education Institution towards Character Education Curriculum: A Systematic Literature Review.” Jurnal Kurikulum & Pengajaran Asia Pasifik 12 (2): 9–21.

Hinchey, Patricia H. 2004. Becoming a Critical Educator: Defining a Classroom Identity, Designing a Critical Pedagogy. Counterpoints Education Series, vol. 224. Peter Lang.

Irfani, Sabit, Dwi Riyanti, Ricky Santoso Muharam, and Suharno. 2021. “Rand Design Generasi Emas 2045: Tantangan Dan Prospek Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan Untuk Kemajuan Indonesia.” Jurnal Penelitian Kebijakan Pendidikan 14 (2): 123–34. https://doi.org/10.24832/jpkp.v14i2.532.

Kolb, David. A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Salam, Maimoona, Dayang Nurfatimah Awang Iskandar, Dayang Hanani Abang Ibrahim, and Muhammad Shoaib Farooq. 2019. Service Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Asia Pacific Education Review 20 (4): 573–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09580-6.

Tan, Soo Yin and Shi Hui Joy Soo. 2020. “Service-Learning and the Development of Student Teachers in Singapore.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 40 (2): 263–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2019.1671809.