Artistic Research in Pandemic Times

February 28, 2022

By 28003

February 24, 2022

By 28804

“Our target is to make India Hindu Rashtra by 2021. The Muslims and Christians don’t have any right to stay here...So they would either be converted to Hinduism or forced to run away from here."

(Rajeshwar Singh, RSS office-bearer, cited in Islam, 2020)

It was not long ago when communal harmony and religious pluralism were synonymous with India. Mahatma Gandhi united a deeply religiously diverse Indian population to fight against British rule. Gandhi, a religious Hindu, mobilized diverse Indian citizenry to an inclusive, tolerant, and religiously plural discourse which helped religious minorities affirm their faith in an inclusive India. Gandhi tried to address the ontological (in)security of religious minorities who were unsure about their security in a Hindu majority nation. The idea of Ontological security (Gidden, 1991) refers to a ‘person’s fundamental sense of safety in the world’, it includes a basic trust of other people and, it is intimately connected to emotions.

It is important to note, Gandhi was murdered on 30th January 1948 by a member of RSS (Venugopal, 2016) Nathuram Godse, who abhorred the idea of Hindu-Muslim unity. Gandhi's long-cherished idea of communal harmony was disrupted when Prime Minister Narendra Modi – a Hindu nationalist leader – rose into power in 2014. Modi moved Hindutva (also known as Hindu nationalism) from the political margins to mainstream politics. So, one can naturally ask, what is the relationship between Hindutva and Gandhi’s inclusive nationalism regarding ontological (in)security and, what different emotional atmosphere Hindutva create compare to Gandhi's interculturality. Possibly, an analysis of the emotional process inscribed in the ontological (in)security script could help to find an answer.

An ontological (in)security approach could provide an interesting insight into the emotional processes of Hindu electorates which has helped Hindutva populists leader Narendra Modi elected as the Prime minister of India and reconfirmed, despite knowing his complicity in the Godhra communal riots (The Guardian, April 7th 2020) when he was the chief minister of the Gujrat state in 2002. An ontological (in)security approach helps in understanding the emotional environment created by such extremist’s (Hindutva) ideology and its violent response against the ‘Others’. Hindutva thrives through the emotional governance (Richard, 2007) communication through emotional messages, and provides emotional security to an insecure Hindu electorate through religion and nationalism while stigmatizing Muslims and Christians. The ontological security approach considers that humans are security seekers by nature, they are always in search of stability, and security while seeking to reduce their 'fear' and 'anxiety'. In this context, 'religion' and 'nationalism' are the two most important identity-signifier (Kinnvall, 2019) which provide stability and security in times of the perceived crisis.

The aggressive rise of Hindutva in the 1980s is a crucial turning point for a secular Indian state, which is on the verge of becoming a Hindu authoritarian state where calls for genocide of Muslims (Aljazeera news, December 24, 2021) and their mob lynching is normalized. Hindutva is radically far-right, hierarchical, authoritarian, and based on the idea of Hindu supremacy. On different levels, Hindutva seeks to repress dissenting views, expunging religious pluralism and secularism from the Indian political discourse. Religious minorities in India, currently, live under the constant fear of being attacked by Hindu extremist organizations such as RSS.

The discourse of Hindutva consists of a populist narrative of nativism, nationalism, and religion. Its appeal became particularly relevant in the time of perceived economic, social and political, or psychological crisis, in which ontological insecurity arises from the attempt to put identity and autonomy in question with anxiety, insecurity and alleged dangers (Laing 1965). In this context, Hindutva leaders frequently incite Hindus by portraying Muslims as rapist and violent, setting a narrative of fear that the Muslim population will take over India in fifty years (Soz, 2016), thus, Hindus will be a minority in their own country; this appears to create ontological insecurity among Hindus who may perceive that their religious identity and autonomy is in danger, thus, they react by supporting Hindutva extremists leaders, and sometimes are complicit in violence against Muslim minorities.

The Indian case shows us how an illusion of ontological (in)security has helped Hindu extremism rise. Modi have been religiously polarizing Indian electorates; he invoked past traumas (Islamic invasion of India) and glories (fantasies of the greatness of the Ancient India and Kingdom of Rama) of a lost Hindu nation. In his recent visit to Varanasi at the Kashi Vishwanath temple, Modi invoked the greatness of the Indian (Business Standard, December 13, 2021) while underlining the atrocities perpetrated under the Muslim rulers; while laying the foundation stone for the Ram temple at Ayodhya, Modi again invoked (Indian Express, August 5, 2020) India’s eternal glory. Setting the emotional political narrative around restoring the Hindu temples in Kashi, Mathura (The Hindu, December 10, 2021) and Ayodhya are also parts of this ontological security; temples represent the symbolic superiority of the mythic spiritual glory of the ancient Hindu nation, and their fall at the hands of Muslim invaders represents national humiliation (national trauma) of Hindus. This narrative generates an atmosphere of ontological insecurity among Hindus who could vent their anger against Muslims.

It shall be noted that the Islamic invasion of India (12th to the 16th centuries) and the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 are some big events that are projected by Hindu nationalists as a historical traumatic event in their effort to generate narratives of constant rage, fear and, anxiety among the Hindu majority, which usually results in Islamophobia and, normalization of violence against Muslims. Central to such narrative construction (Kinnvall, 2016) are the collective identity and collective emotions, such as love for the nations or hate, fear, or disgust for the strange others such as Muslims. An ontologically insecure Hindu electorate demands unquestioned loyalty to its imagined nation, to its national history, and its sacred culture. Thus, these narratives of a sacred Hindu land became the objects of the people's imaginations onto which fantasies of national unity are projected to rescue the belief in the core and stable identities (Kinnvall, 2016) which is Hindu religion and culture. The use of violence, coercion and threats are justified by Hindutva to protect their core identities; because of this, Hindutva is also referred to as a muscular nationalism (Banerjee, 2012).

The re-invention of nationhood and religion (Kinnvall, 2019) in Hindutva discourse is aimed at 'healing' several ontological insecurities by which the Hindu majority suffers. Among such fears and emotional responses of Hindutva has been manifested in the forms of; Love-jihad, Corona-jihad (Milli cornicle, April 19, 2020) UPSC-jihad (The Print, November 18, 2020) mob lynching of Muslim (BBC, September 2, 2021) and Dalits, disrupting Muslim prayers (NDTV, December 18, 2021) vandalizing Churches (November 30, 2021) and boycotting Muslims vegetable (News Click, April 13, 2020) vendors and sellers.

Gandhi tried to heal public anxiety and insecurity through his inclusive nationalism. He mobilized people to gain political freedom from British colonialism. Nevertheless, Gandhian nationalism was not narrow or exclusive but meant for the benefit of the whole of humanity. He tried to make public ontology secure through his idea of inclusive nationalism and intercultural unity. Gandhi believed in inclusive nationalism irrespective of religion, caste, and class. For Gandhi, nation was to improve the living conditions of the people (Patnaik, 2019) or to "wipe away the tears from the eyes of every Indian". Gandhi was inspired by the Hindu religious and spiritual values promoting Hindu ways of life, discipline, fasting method, and mental purity. His political actions (civil disobedience, fasting) were in line with the Hindu religious ideas of truth and non-violence.

However, Gandhi was concerned about the deep communal tension among communities (Hindu-Muslims, Dalits-Upper castes, rich-poor), thus managing such tensions and averting serious conflict was on top of his political agenda. He believed that communal violence could trigger ontological insecurities among communities and could jeopardize the freedom struggle and communal harmony among them. His religiously plural discourse helped him create an ontologically secure environment and, cementing ties with Muslims and other religious minorities and lower-caste Hindus.

By employing an inclusive intercultural approach based on mutual respect and equal regard, Gandhi stressed the fundamental unity of all religions and tolerance for different faiths. At the ontological (in)security level, these methods, and processes reduced the anxiety and fear among diverse communities, assuaged fear of religious minority from the majority, and helped create a feeling of security. His idea to establish a ‘just society’ (Jahanbegloo, 2020) was also an ontological security provider to all Indians. Contrastingly, Hindu nationalists are instilling ontological insecurity among Hindus to exclude Muslims, to establish Hindu supremacy which has paved a way for an unjust society.

From the aforementioned discussion, it shall be clear that Hindutva, by creating an atmosphere of insecurity and anxiety has made the Hindu public ontologically insecure whereas Gandhi, tried to provide ontological security to the public by building an environment of religious harmony and intercultural faith. This shows that by looking into the emotional process enacted within Hindu nationalism through the idea of ontological (in)security it is possible to outline the major differences between Gandhian inclusive nationalism and the Hindutva exclusionary discourse.

References:

Banerjee, Sikata (2012) Muscular nationalism: gender, violence and empire in India and Ireland, 1914–2004 (New York: New York University Press)

Giddens A, (1991) Modernity and Self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity

Islam, Shamshul (2020) RSS founders 'endorsed' Nazis: It’s well-nigh impossible for races, cultures to 'coexist', Counterview, available at https://www.counterview.net/2020/09/rss-founders-endorsed-nazis-its-well.html

Jahanbegloo, R (2020) The Mahatma as an intercultural Indian, available at https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/the-mahatma-as-an-intercultural-indian/article32747352.ece

Kinnvall, Catarina (2019) Populism, ontological insecurity and Hindutva: Modi and the masculinization of Indian politics, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, DOI: 10.1080/09557571.2019.1588851

Kinnvall, Catarina (2016) Feeling Ontologically (in)secure: States, traumas and the governing of gendered space, Cooperation and Conflict, Sage publication, DOI: 10.1177/0010836716641137

Laing R. D (1965) The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness, Penguin Psychology, Paperback

Patnaik, P (2019) For Gandhi, nationalism was based on understanding what was required for people to be free, available https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/mahatma-gandhi-nationalism-capitalism-marx-6054147/

Richards B. (2007) Politics as Emotional Labour. In: Emotional Governance: Politics, Media and Terror. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230592346_8

Soz, A. S. (2016) RSS Claims About Rapid Growth of the Muslim Population are Simply False, available at https://thewire.in/politics/rss-claims-rapid-growth-muslim-population-simply-false

Venugopal, V (2016) Nathuram Godse never left RSS, says his family, available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/nathuram-godse-never-left-rss-says-his-family/articleshow/54159375.cms?from=mdr

Web resources:

Aljazeera: India: Hindu event calling for genocide of Muslims sparks outrage, available at

BBC: Beaten and humiliated by Hindu mobs for being a Muslim in India, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-58406194

Business Standard: Kashi Vishwanath Dham is testament to India's culture, history: Modi, available at https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/kashi-vishwanath-dham-is-testament-to-india-s-culture-ancient-history-pm-modi-121121300642_1.html

Indian Express: Ram Mandir Bhumi Pujan: Full text of PM Narendra Modi’s speech in Ayodhya, available at https://indianexpress.com/article/india/ram-mandir-bhumi-pujan-full-text-of-pm-narendra-modis-speech-in-ayodhya/

Indian Express: Delhi: Site of proposed church ‘vandalised’ in Dwarka, religious group returns to Punjab, available at https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/delhi-dwarka-church-vandalism-ankur-narula-ministries-7648358/

The Hindu: In Parliament, BJP pitches for Krishna Temple at Mathura, available at

The Milli Chronical: OPINION: Corona-Jihad of Hindutva vs Communists of Kerala

available at https://millichronicle.com/tag/corona-jihad/

The Print: ‘UPSC jihad’ show offensive, could promote communal attitudes — govt in affidavit to SC, available at https://theprint.in/india/governance/upsc-jihad-show-offensive-could-promote-communal-attitudes-govt-in-affidavit-to-sc/547415/

NDTV: 'Must Say Bharat Mata Ki Jai': Gurgaon Muslims Trying To Offer Namaz Told, available at https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/gurgaon-namaz-row-must-say-bharat-mata-ki-jai-gurgaon-muslims-trying-to-offer-namaz-told-2657225

News Click: Muslim Vegetable Vendor Abused, Thrashed in Delhi, One Arrested, available at https://www.newsclick.in/Muslim-Vegetable-Vendor-Abused-Thrashed-Delhi-One-Arrested

The original article is published in Alice news.

https://alicenews.ces.uc.pt/index.php?lang=1&id=37275

February 15, 2022

By 27520

As part of her dissertation on “The Image of Britain in Czechoslovak Media Discourses between 1939 and 1948,” 2018 Sylff fellow Johana Kłusek—with the help of an SRA award—reconstructed a “test” discourse on the British image of Czechoslovaks based on resources at the British Library. Among her findings is that whereas Czechs admired just about all things British, the Brits did not reciprocate that interest.

* * *

The origins of thinking about the Other as “the other culture” (and only more recently “the other nation”) can be traced back to medieval times. Any travelogue or chronicle would include remarks on the Others, whether the inhabitants of a faraway country, citizens of a nearby city, or members of a different ethnic or religious group. For a long time, stereotypical images were perceived as objective categories through which one could reconstruct an ethical and aesthetic worldview of different cultures or nations (Leerssen 2016). In Europe this tendency was accelerated in the nineteenth century. The continent witnessed a rise of three phenomena: the birth of mass media, self-determination of nations, and antagonistic understanding of international relations (Hahn 2011). The combination of these factors led to a deepening of both heterostereotypes (opinions that a group holds about other groups) and autostereotypes (opinions that a group holds about itself). However, a full realization of the threat that these often dangerously ingrained mental concepts pose to intercultural and international relations emerged only as a result of World War II and the Holocaust.

Despite the fact that outright stereotypes are today less present in public discourses, they keep influencing interactions in milder forms between individuals as well as groups. People tend to generalize about various outgroups based on deep-rooted preconceptions, distorted individual experiences, and media images propagated by different power groups. By observing and analyzing the making of stereotypes in history, we can better understand how dangerous othering can be when propelled by negative sentiments as well as by positive ones. On a more general note, research focused on discourses about the Other can reveal the mechanisms through which we naturally orient ourselves in the world.

Conciliation of Conservatism and Socialism in the Czechoslovak Image of Britain

In my dissertation research I examine Czechoslovakia in the period of its major existential crisis. Britain is studied as a significant Other, onto which Czechs projected their visions and hopes as well as fears and frustrations during World War II. The image of Britain between 1939 and 1945 is prevalently appellative and corresponds with the main features of the traditional European stereotyping of the country, as described by Ian Buruma (1998). Czechs admired British conservatism, adherence to principles, rule of law, tradition, and taste, as well as their humor, friendliness, and openness to other cultures. The history of ascribing those qualities to the British is long, and the Czech discourse (created mostly by the exile community in London) does not come with any radical novelties.

The image also proves Buruma’s thesis about the utilitarian usage of Anglophilia, as continental observers tend to attach themselves to British culture when they get disappointed with old referential Others. In this way Anglophilia allowed for the liberation of Czechs from the German-Russian geopolitical captivity. Also, Churchill’s “sweat and tears” mentality provided a much-needed role model in the time of the debilitating German occupation.

Most importantly, though, the image illustrates a strong need to find a new role in the radically changing world. During the quest, Czechs were interestingly able to combine admiration for the classic conservative features of British culture (or its distorted images) with admiration for the new left-wing ideas and policies born from the war circumstances. In this way, they could easily look up to the West and the East at the same time. One can thus confidently claim that the road to the embrace of the Soviet Union (as seen in the Communist Party’s victory in the parliamentary election of 1946, followed by the communist coup d’état of February 1948) was simplified by the conciliation of highly contradictory discourses that are seemingly unrelated. Britain serves here as a polarizing projection screen.

SRA and a “Test”Discourse

To conduct the prime research briefly discussed above, I use discourse analysis of a number of Czech newspapers of the time (including Čechoslovák, Nová svoboda, and Mladé/Nové Československo). However, to interpret the data correctly and precisely, I needed to reconstruct a “test” discourse on the British image of Czechoslovaks. Sylff Research Abroad allowed me to do that and to gather relevant articles from resources of the British Library. The findings helped me to partly answer such questions as: Did the British share the affection that Czechs felt—or expressed in the media discourse—toward them? Was their relationship in any way special?

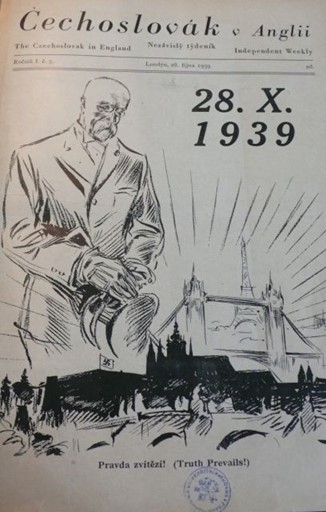

Cover of the Czechoslovak in England, featuring President Masaryk and a combined panorama of Prague, London, and Paris.

In the end, three major sets of observations were made. Firstly, the British interest in Czechoslovaks and their culture changed over time. At the beginning of the war, coverage of the cultural output of Czechs living in the country and general interest in the recent as well as older history of Czech lands was strong, but it decreased in later phases of the war. A broader wartime spirit of allyship played a significant role in these dynamics. The spirit was massively encouraged by the propaganda of both the British government and the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, primarily during the bombing of Britain in 1940 and 1941. Secondly, there is no evidence that the British were interested in Czechoslovakia disproportionally more than in other allied nations. Thus, if there was any “special relationship” between the two nations, it was rather one-sided. Thirdly, articles collected from British wartime newspapers (The Times, Manchester Guardian, and Daily Telegraph) prove that British discourse regularly used stereotypes about Czechs. The image consisted of highly idealized concepts of the country defined by a love of liberty, as a country that has always bravely striven against the threats from outside. The positive nature of those stereotypes is comparable to the nature of the stereotypes expressed at the time by Czechs when referring to the British and British culture.

Studies of opposite discourses such as the one I have just presented allows us to observe the efficiency of national propagandas, the longevity of stereotypes, and changes in their understanding as well as their usage. Their value also lies in the fact that they allow us to look at things from less obvious angles. As discourses are often influenced by many subconscious motives of many individuals, they tend to reveal tendencies of whole societies that would otherwise remain unnoticed. The Czechs’ largely blind admiration of everything British is good proof of that.

References

Hahn, H.H. 2011. Stereotypy—tożsamość—konteksty: Studia nad polską i europejską historią. Poznań: Wydawnictwo poznańskie.

Leerssen, J. 2007. “Imagology: History and Method.” In Imagology: The Cultural Construction and Literary Representation of National Characters, edited by M. Beller, and J. Leerssen, 17–32. Leiden: Brill.

January 11, 2022

By 29256

Tamas Dudlak, a 2021 Sylff fellow, offers a comparative view of the foreign aid policies of Hungary and Turkey, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa. The former focuses its efforts on protecting Christians, while the latter primarily supports Sunni Muslims, each with a different set of motivating factors. Dudlak also discusses differences between these “emerging donors” and traditional Western donors, such as in their approach to aid distribution and how they are seen by recipients.

* * *

Recently, many have suggested similarities between Turkish and Hungarian political developments in the recent decade.[1] However, few have attempted an in-depth comparative analysis of the political systems of the two countries. In my research, I compare the characteristics of and recent trends in the foreign aid policies of Hungary and Turkey, focusing specifically on their activities in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

This issue is particularly relevant in the era of mass migration and the existence of a conflict zone along Europe’s southern and eastern borders. It is essential that Hungary, as part of the European Union, and Turkey, as a stable political system in the Mediterranean, coordinate their development policy concepts concerning the southern and eastern crisis zones. To do so, it is necessary to understand the factors that motivate each to develop an increasingly prominent humanitarian policy.

Landscape of Foreign Aid in Turkey and Hungary

Various government-affiliated and government-related organizations and projects in Turkey and Hungary are prominent in distributing different types of foreign aid. These are, on the Turkish side, AFAD (Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency), TİKA (Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency), Diyanet (Presidency of Religious Affairs), and Türkiye Bursları (scholarship program of Turkey for international students); and on the Hungarian side, Hungary Helps, Hungarian Red Cross, Stipendium Hungaricum (scholarship program of Hungary for international students), and various humanitarian programs of the Hungarian churches. The fields of action of these state agencies and government-related organizations range from disaster relief aid, education assistance, post-conflict reconstruction, and direct investment to culturally related assistance (in such areas as language or religion) for conflict-ridden communities.

Turkey has already pursued an active policy in its neighboring Syrian territories during the expansion of the Middle Eastern conflict zone (especially from 2011 onward) and has engaged in an increasingly broader humanitarian policy during the protracted war in its immediate neighborhood.

Compared to Turkey, the Hungarian leadership realized the importance of active and coherent humanitarian action in the Middle East. This was because the 2015 migration crisis prompted a reassessment of the role of the potential migrant-sending countries in the Hungarian political discourse, making it in the country’s interest to assist conflict-affected areas. In the Hungarian government’s view, given the country’s limited financial and material capacities and limited public support for such activities in remote areas, this can best be done by assisting Christians in the Middle East and Africa to minimize migration in these conflict-affected areas.

Another reason for the increased Hungarian and Turkish activism in these previously neglected areas is that both countries have started to build up their relations with governments and local representatives of emerging countries beyond their traditional Atlantic relations, a development that undoubtedly serves economic and political interests (diversification of relations). The economic crisis of 2008 and the shift in international power (the growth of China and the rise of regional middle powers) have further reinforced the process whereby the European periphery—Hungary and Turkey—is forging its own mechanisms for direct relations with developing countries.

In the case of underdeveloped bilateral relations, one of the most effective ways of doing this is to provide targeted assistance to these countries in the form of joint investments or development projects, as such joint platforms also help to get to know each other and thus pave the way for institutional (permanent) economic and political relations.

As emerging donors, both Hungary and Turkey have a strong humanitarian presence relative to their economic and political weight, and the MENA region is a priority area for their humanitarian aid programs. Turkey is often referred to as the most generous country. This is evidenced by the fact that in 2017, Ankara spent the world’s highest proportion (1%) of total GDP on humanitarian assistance.[2] This active engagement is an integral part of international image building for Turkey, which is aspiring to be a global peace broker and a development state.

Hungary’s niche policy is mainly conducted through the Hungary Helps program,[3] which focuses its humanitarian action on a specific type of community, namely persecuted or endangered Christian communities in the Middle East. As this target group represents only a minor part of the populous Middle East, Budapest could achieve spectacular successes with a relatively small amount of money even while minimizing its political interventions in the target countries.

Emerging versus Traditional Donors

There is a difference between the “Western”actors, referred to in the literature as “traditional donors,” and the “emerging donors” in their approach to foreign aid distribution.[4] Traditional donor countries have a rather strategic approach, working in well-defined, “safe”areas where the impact of their activities can be well assessed and unnecessary complications with local powers can be avoided.

By comparison, new aid donors have adopted a more structuralist-functionalist approach. They tend to rely on the cultural links with locals, shared experiences, and common identities (soft power elements). New types of donors often take risks, both in terms of the choice of the target area and in terms of the lower degree of cooperation, or embeddedness, with local authorities. The latter is clearly due to their lack of contacts and, in this context, their weaker political advocacy skills.

Turkey and Hungary are “new” donors with a relatively clean slate and are more reliable for the locals than traditional Western donors with imperialist ties. These two countries have the advantage of implementing services of Western quality and techniques with a non-Western attitude and background—that is, they do not attach conditions to humanitarian aid such as the rule of law, democracy, and some degree of liberal market economy.

For both countries, the areas in which they are active in their foreign aid policies—supporting Sunni Muslims in the case of Turkey, the protection of Christians in the case of Hungary—play an essential role in the domestic process of seeking identity. The political leadership of both countries is striving to serve as a model for the international community. Although the aim of humanitarian aid is the same (civilizational discourse), the emphasis differs: for Turkey, active foreign aid policy is more an attribute of its middle power status and a cornerstone of its security, while for Hungary, growing involvement in humanitarian activities is primarily intended to strengthen the coherence of the government’s migration policy.

Accordingly, potential migrant communities should be assisted locally and thus encouraged to stay in their original environment, which requires development of infrastructure (such as schools, hospitals, churches, and public utilities) in the war-torn countries of the Middle East. Moreover, the Hungarian government defines itself as a Christian democracy; thus, it cannot be indifferent to Christians living under persecution and in conflict-ridden areas. This is reinforced by the discursive effort of Viktor Orbán to present Hungary as a “defender of Christianity.”[5]

Hungary and Turkey constitute emerging donors with vast opportunities in the international humanitarian aid arena. The current governments of the two countries made significant steps toward improving the visibility of their respective countries in line with the ideological background of the political leadership. These are only the first steps toward lasting relationships between donors and recipients, and only the future can tell the pace and direction of institutionalization of humanitarian assistance policies in these countries.

[1] See, for example, Ian Bremmer, “The ‘Strongmen Era’ Is Here. Here’s What It Means for You,” Time, May 03, 2018, https://time.com/5264170/the-strongmen-era-is-here-heres-what-it-means-for-you/, and “How Democracy Dies: Lessons from the Rise of Strongmen in Weak States,” The Economist, June 16, 2018, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2018/06/16/lessons-from-the-rise-of-strongmen-in-weak-states.

[2] https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/2019/10/01/turkeys-streak-as-most-generous-country-in-the-world-continues

[3] https://hungaryhelps.gov.hu/en/

[4] Jin Sato, Hiroaki Shiga, Takaaki Kobayashi, and Hisahiro Kondoh, “How do ‘Emerging’ Donors Differ from ‘Traditional’ Donors? An Institutional Analysis of Foreign Aid in Cambodia.” JICA-RI Working Paper no. 2, JICA Research Institute, March 2010, https://www.jica.go.jp/jica-ri/publication/workingpaper/jrft3q00000022dd-att/JICA-RI_WP_No.2_2010.pdf.

[5] HírTV, “Tusványos 30 – Orbán Viktor teljes beszéde” [Tusványos 30 –The Full Speech of Viktor Orbán], YouTube video, July 7, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q4KPjPCUAUk.