A decade ago, then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced a policy aimed at promoting more women to leadership positions in Japan—a country that has long ranked near the bottom in the Global Gender Gap Index. The pace of progress since then, though, has been embarrassingly slow. Thanh Nguyen (Waseda University, 2014) used an SRG award to analyze corporate data over the past decade to identify where improvements have been made and what more needs to be done to enhance women’s boardroom presence.[1]

* * *

In spring 2014, then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a speech on “A New Vision from a New Japan” at the World Economic Forum, stating, “Japan must become a place where women shine. By 2020 we will make 30% of leading positions to be occupied by women.” This led to an increase in the number of female board directors, but Japan still failed to achieve the 30% target by 2020 and had to push back the target date by up to a decade.[2] The situation today is still not promising, as the Global Gender Gap Index in 2023 ranked Japan 125th out of 146 countries; the country has remained near the bottom of the list over the last 10 years. Will Japan be able to reach the 30% milestone by the revised deadline of 2030?

In my research, I gathered updated data about female leadership in Japan from 2012 to 2023. I first measured the impact of recent changes in Japanese policy and law aimed at promoting the appointment of women to management and leadership positions, focusing on Abe’s “Womenomics” policy launched in 2013 and the Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace implemented in April 2016. I examined whether firms appointed more female directors during the policy period compared with earlier periods.

Second, I examined the critical mass of female directors and the firms that succeeded in increasing the number of female directors to this level. Critical mass is defined as the number of female directors needed to affect policy and induce real change. I identified firms as being successful in reaching critical mass if 30% or more of their board members were women—the target figure set by the Japanese government. My main research question was whether gender policies actually helped to increase the number of female directors, especially up to critical mass.

Scrutinizing Womenomics Policies

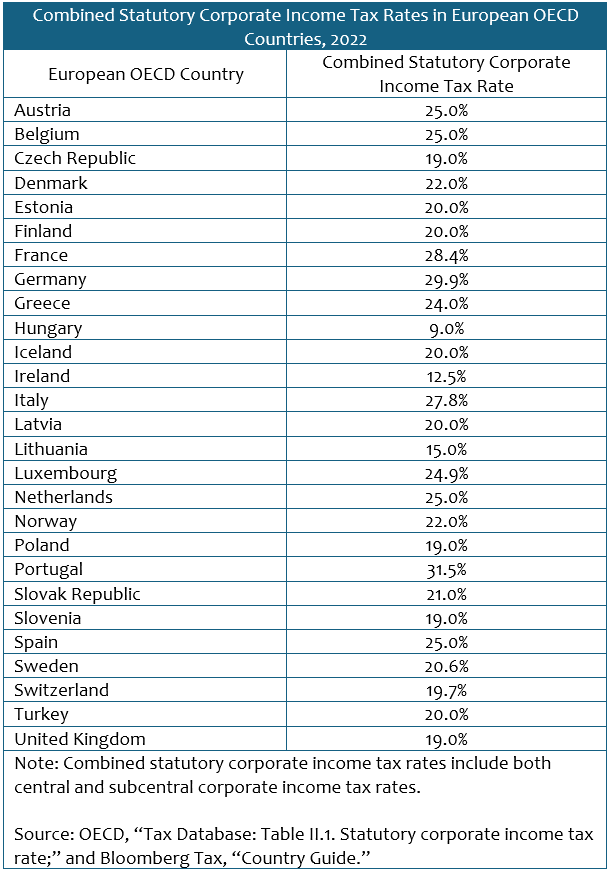

Many countries have introduced a mandatory or voluntary quota for female leaders to address gender inequality. For example, Norway has a 40% female board membership quota, while Britain maintains a 25% female board membership target. By contrast, the Japanese government promotes female leadership not with a quota but through its Womenomics policy package that encourages large corporations to promote gender- and employment-related policies. In particular, firms have been advised to establish and disclose their action plans to improve gender equality and to disclose relevant data.

To answer my research question, I collected data on the directors at listed firms in Japan from the Yakuin Shikiho (Executive Officers Handbook), published by Toyo Keizai Inc., which includes the name, age, position, gender, place of birth, education, and previous experience of each director. My final sample consisted of an unbalanced panel of more than 40,000 firm-year observations from 2012 to 2023. I then created a group of variables representing the characteristics of the board, including “total number of board members,” “total number of female board members,” “ratio of female board members,” “chairperson gender,” and “CEO gender.”

30% Target Reached by Only Small Minority of Firms

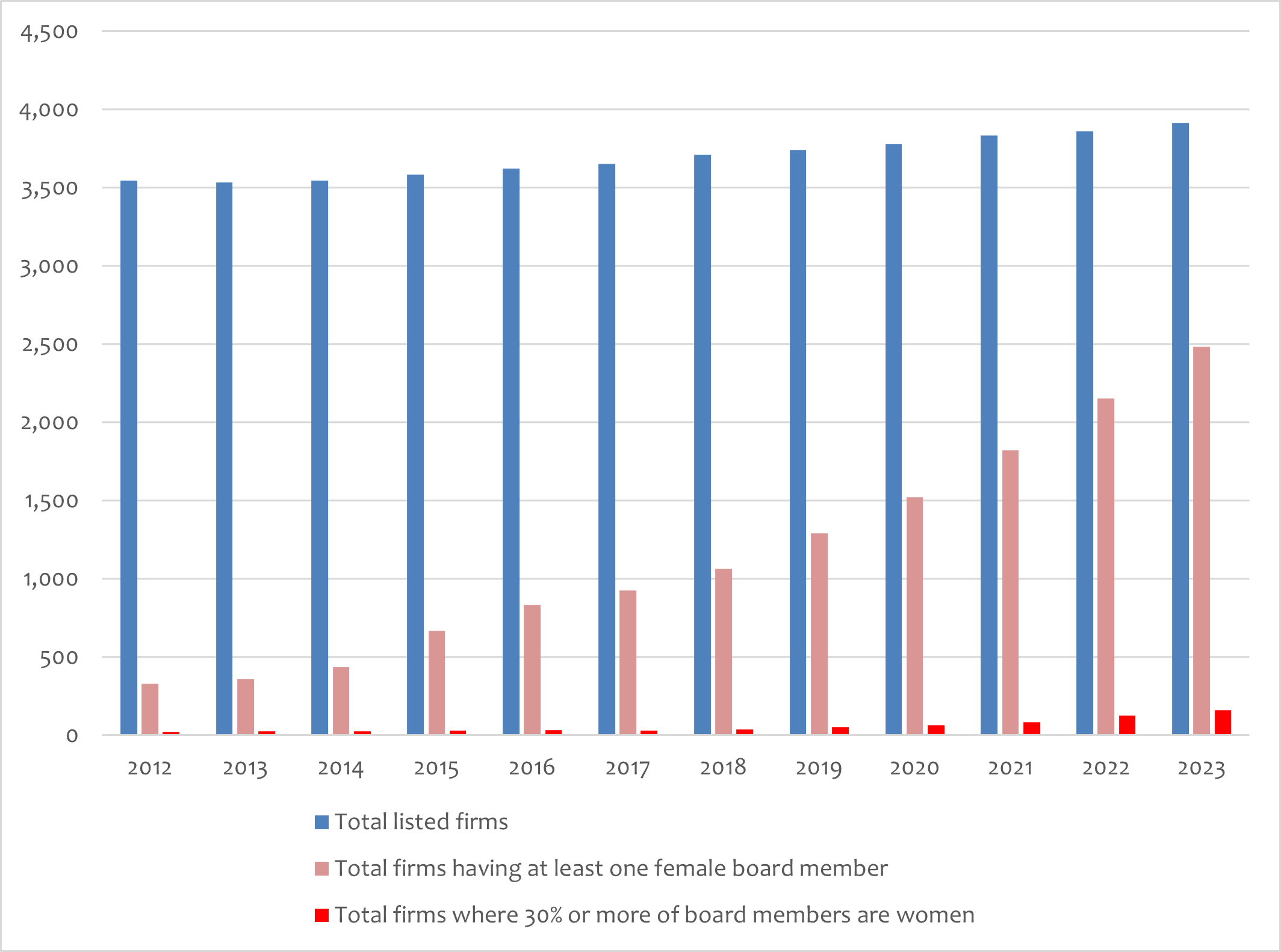

I found that only 9% of surveyed firms had at least one female board member in 2012 but that this figure increased gradually each year, climbing to 63.4% in 2023, with 2,482 out of 3,915 listed firms having at least one female board director (Figure 1). This indicates that many more firms appointed female board directors during the years of Womenomics. The steady uptrend was unaffected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Policymakers may be happy with these changes in corporate governance and claim that the Womenomics policy package has been effective. The truth, though, may not be that rosy. When I calculated the share of female board members and grouped the firms according to this percentage, I found that the group claiming shares of 30% or higher accounted for only 0.59% of all firms in 2012 and a still very low 4.06% in 2023.

This figure has been increasing gradually each year, to be sure, but the pace has been very slow, and the spread is consequently very small. In 2023, among the 3,915 listed firms, only 159 met the 30% target for female board members. This means that although more firms appointed women to the board during the Womenomics years, the number of appointees has been minimal. If this situation continues, Japan will fail for the second time to reach its target of “30% of leading positions to be occupied by women.”

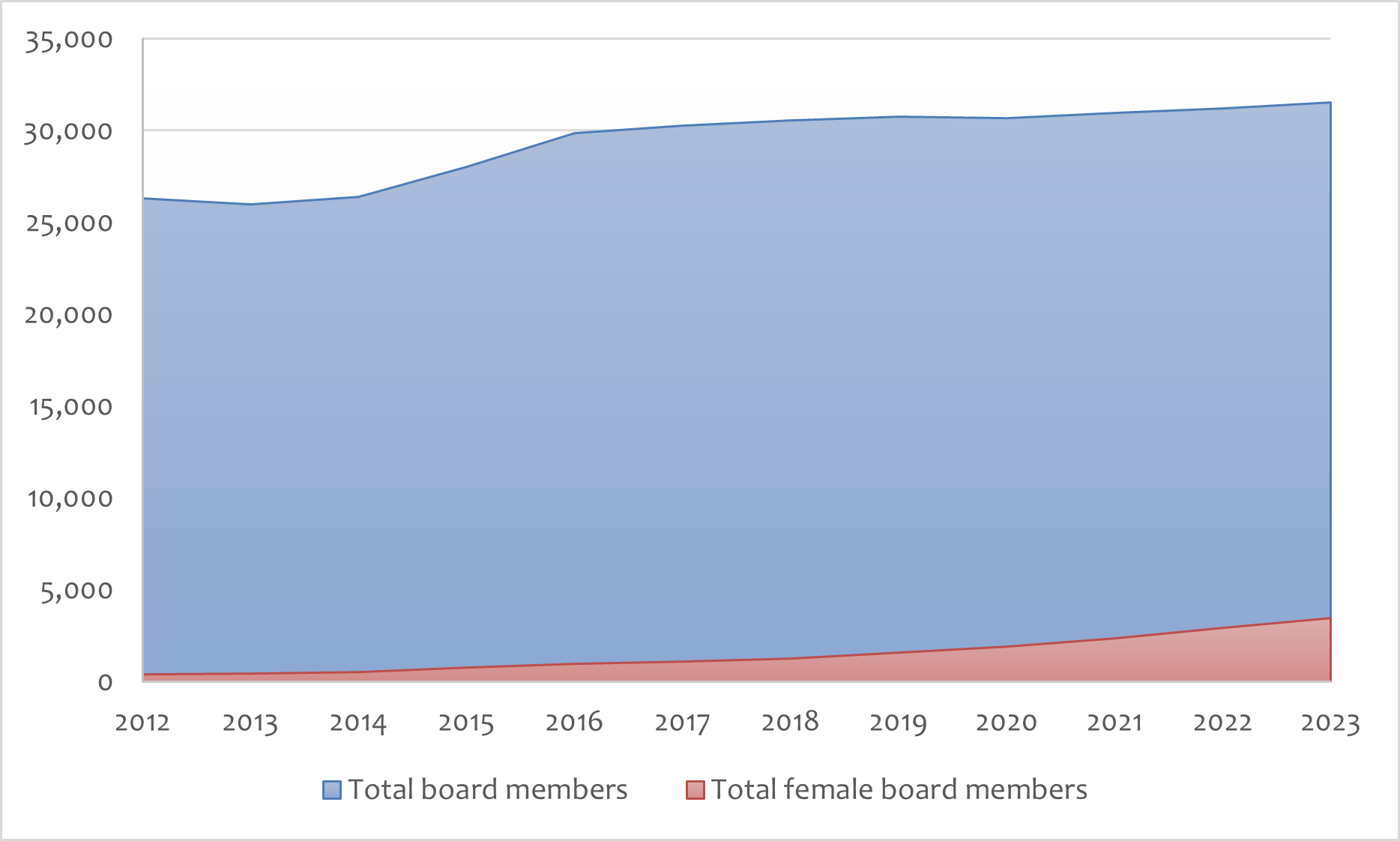

I also examined the number of women serving as the chair, the CEO, and a board member for each year from 2012 to 2023 and found that there has been no uptrend for either the chair or CEO. These figures fluctuated year on year with a very small change spread. Among the 31,520 board members in 2023, there were only 21 chairwomen and 54 female CEOs. In other words, of the 3,915 listed firms, only 54 firms were headed by women—hardly a robust picture of female leadership in Japan.

Figure 1. Share of Female Board Members, 2012–2023

As for board members, in 2012, only 374 of the 26,294 members were women, accounting for a mere 1.42% of the total. If chairwomen and female CEOs are deducted, the total number of female directors in 2012 was 335. Figure 2 shows that even with the jump in the number of female directors from 2012 to 2023, the ratio of female board members was still small. My data shows that in 2023, the percentage of female board members was 10.93% in 2023; in other words, males still occupy 89% of the boardroom. Without fundamental changes, the chances of Japan reaching the 30% target by 2030 appear bleak.

Figure 2: Number of Female Board Members, 2012–2023

I also examined the relative shares of outside and inside female directors. In 2023, outside directors made up 84.33% of the total, implying that firms have tried to increase the number of female directors by tapping human resources from outside the company, appointing such professionals as business consultants, university professors, and leaders of other firms. Indeed, it is easier for firms to appoint a female director from outside the company, since nurturing and promoting female employees to take on management responsibilities takes time.

This pattern highlights another challenge for Japanese corporations: the small pool of qualified female candidates for leadership positions, both inside and outside the firm. Appointing outside female directors is, at best, a short-term strategy, as even the external supply of qualified candidates is small. This is proven by the fact that outside female directors often serve on the boards of several firms. This situation will not fundamentally change until firms begin actively recruiting more female employees and providing them with opportunities for promotion to senior and leadership positions.

Need for Drastic Change

My research was an attempt to provide an overview of women empowerment efforts in Japan over the last decade and to present updated data about female leadership. It led to new findings on the number of female board directors during the twelve years of Womenomic policy (2012–2023).

During these years, corporate governance reforms resulted in more female directors, especially outside directors, being appointed to executive boardrooms, compared with the years before the policy’s implementation. Policies promoting female leadership thus appear to have been effective for listed firms. However, they have had no tangible impact on top positions, like corporate chairs and CEOs. And Japan may once again fail to reach its 30% target without drastic changes over the next six years.

These findings can serve as meaningful references for investors, corporate leaders, and policymakers. There have been calls for stronger measures to promote gender equality both inside and outside corporate settings so that this target can be reached by 2030. Policymakers need to do more than simply ask firms to hire more women and elevate them to leadership positions. And investors, especially institutional investors, must perform their stewardship duties by engaging directly with the companies in which they invest, persuading management teams and board directors to promote gender diversity, which can, in turn, create more sustainable, fairer, better-run, and faster-growing companies.

[1] This is a short English summary of a paper by the author that was originally published in Japanese. The full Japanese version can be found at: https://www.jsri.or.jp/publish/review/pdf/6402/05.pdf.

[2] https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20200626/p2a/00m/0fp/014000c.

References

Kubo, K. and Nguyen, T. T. P. 2021. Female CEOs on Japanese corporate boards and firm performance. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 62, 101163.

Nguyen, T. T. P. 2021. Effects of board gender diversity on firm investment and performance. Waseda Commercial Review, 461, 47-92.

Nguyen, T. T. P. and Thai, H. M. 2022. Effects of female directors on gender diversity at lower organization levels and CSR performance: Evidence in Japan. Global Finance Journal, 53, 100749.

Nguyen, T. T. P. 2024. Nihon ni okeru josei no enpawamento: Tannaru shinboru kara kuritikaru masu e? Shoken Rebyu, 64(2), 115–129.