This report is based on the master’s research by Soumya Bhowmick, a Sylff fellow at Jadavpur University, India, in 2014—15. It originally appeared in FIRSTPOST. a web-based leading media in India. Bhowmick, currently research assistant at Observer Research Foundation’s Kolkata Chapter, continues writing on the changing socioeconomics of the potters’ community known for the terracotta Bankura Horse, which is historically valued in Indian society, especially West Bengal.

* * *

The norwesters in the potters’ village of Panchmura is magnificent in ways more than one. The extremely dry atmosphere during the summer months of April–May make one compare the place to a hot desert with red dust smeared all over your clothes. This period is marked by the holy time of Baisakh, when the potter’s wheel is stopped as it is believed that during this time Lord Shiva appears from the wheel. Many justify it with a scientific reason: that the terrible heat easily exhausts the artisans and causes cracks to develop in the pottery items. After a heavy rainfall, the sweet petrichor is one of the strongest in this part of the town owing to the large amounts of terracotta clay all over the place. The potters are relatively free during these months and are very eager to have a chat with you over tea in their workshops.

Mahadeb Kumbhakar, 56, proudly proclaims, “The trademark Bankura Horse [uniquely styled terracotta horse made in Bankura] came into existence because people would offer them as a mark of devotion to different deities and even on the tombs of Muslim saints. It is used as the official crest motif of the All India Handicrafts Board.” He woefully adds that a large number of youngsters in the area, including his own son, have moved to Kolkata not only because of the money but also because of their inability to commit to the labor required for this kind of artistry. Mahadeb justifies that there is no harm in working in an office while at the same time being a marginal potter. That way, the skill is never wiped out from the family.

Panchmura village near Bishnupur, Bankura District, is one of the main hubs of terracotta in West Bengal. Historically, the politically stable Malla Kingdom indulged in a lot of cultural activity and invited high caste Brahmins, expert craftsmen, and masons to Bishnupur, and through the amalgamation of religion and culture, these people contributed largely to the trade and commerce of the region. The Bankura artisans gradually scattered to different parts of the country, but today only the few remaining in Panchmura are still striving to keep this art form alive.

The origin of terracotta in India can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization. Terracotta came into existence in Bengal due to the unavailability of stones and large endowments of alluvial soil left by the main rivers in the Bankura District: Damodar, Dwarakeshwar, and the Kangsabati. The soil thus gets a perfect blend and density for it to be crafted intricately and fired in order to produce the required terracotta products. A Panchmura artisan says that a Durga idol made in Bankura is at least three times as heavy as an idol of the same size made in Kolkata because the soil found in Bankura is much more dense and mineral rich, making the crafting process extremely laborious.

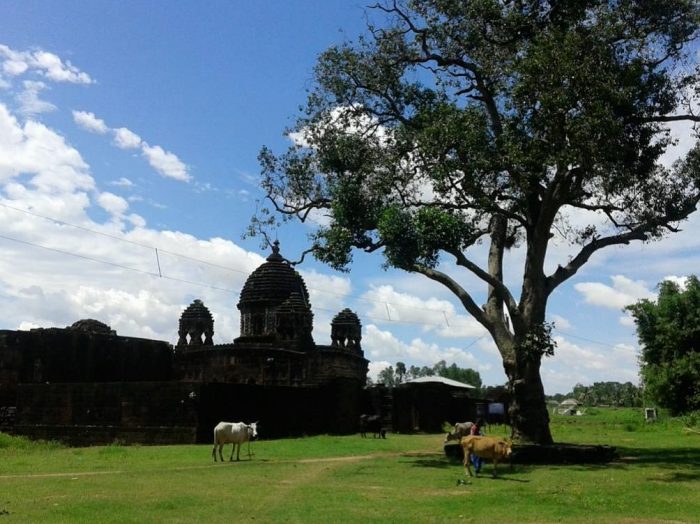

The cultural transformation in the community is well captured through the terracotta craft embossed on the walls of various temples, towers, and smaller objects in the region. Many scholars have interpreted this as a translation of the primitive Sanskrit literature into mainstream Bengali narratives that allowed the emergence of such popular cults in Hinduism as Durga, Krishna, and Kali. The terracotta temples in Bankura are mostly Radha-Krishna temples, which drew inspiration from Vaishnavism.

The Munshiganj District in Bangladesh, which is close to the confluence of the Padma and Brahmaputra rivers, is a storehouse of terracotta work on the other side of Bengal. Almost all the temples are dedicated to Shiva, and the temple roofs are distinctly different from the ones found in Bankura, as the ones in Munshiganj are more longitudinally conical.

Narratives on terracotta were sources of both information and entertainment for the people, depicting stories from the mythological texts of Ramayana, Mahabharata, Hitopodesha, Jataka, and Panchatantra. There has been emphasis on scenes indicating rural life, farming techniques, male and female dancers, musicians, and village gardens. Bengal architecture is uniquely different from the architecture that coincided with the Muslim rule in India, and by the end of the sixteenth century a new Bengali style of temple art became prominent and established itself as an artistic Hindu expression.

Unlike most of the other art forms that emerged with the purpose of aesthetic value in creativity, terracotta was made to serve practical purposes, such as food and water storage, weapons, and utensils. From being necessary commodities of daily use, these artifacts evolved into something more creative imbued with a high level of craft, making terracotta a cultural commodity with great marketing potential.

The Bankura District is known for its popular handicrafts in the form of terracotta, the Dokra handicrafts of Bigna, the stone craft of Susunia, and the Baluchari silk of Bishnupur. The global interest in Indian terracotta can also be found in a letter by Swami Vivekananda regarding the time when Okakura Kakuzo, the famous Japanese scholar, visited India in 1901–1902. Okakura was extremely impressed by the craftsmanship of a common terracotta vessel used by the servants and, owing to the fragility of these handicrafts, he requested Swami Vivekananda to replicate the piece in brass for him to carry it back to Japan.

Terracotta is still of high interest in the global market, and Panchmura, Surul, Chaltaberia, and Shetpur-Palpara are the major villages in West Bengal that export terracotta to international markets. However, the artisans face a number of key problems that are crippling the market for this kind of artwork, including the issues of equipment, transportation, and other logistical problems; the lack of interaction between the artisans and the urban consumers in Kolkata; and the high dependence of terracotta artisans on local patronage. Moreover, the inadequate capital, sluggish marketing, and falling demand are causing these marginalized artisans to become extinct, and the lack of interest from the new generation along with insufficient government schemes further add to the woes.

Toton Kumbhakar, 30, says, “We get some idea of consumer preferences in the handicrafts fair in Kolkata every year, where people mostly demand the Bankura Horse, since it has a certain traditional value as a regular showpiece in the Kolkata households.” The potters admit that they charge much more for the handicrafts in Kolkata and are also financially dependent on the various regional festivals, for which they make large idols for relatively hefty prices.

The terracotta temples in Bishnupur show a much better quality and precision than the artifacts being produced today. For example, the details on the terracotta tiles used in the temples are much more intricate and portray a more complex network of lines, curves, and dots. How is this possible despite improvements in technology and intruments? The extinction of skill-specific labor is the answer to this. According to the locals, the process of terracotta production in Bankura previously included three major classes of workers: the clay collectors and sievers, who would give a fine texture to the clay; the artisans, who would add the intricate details; and finally the market traders. There is no specific class of labor anymore for each of these three roles.

“Bankura is my native place, and so terracotta has a special place in the lives of my family members,” says an urban consumer in Kolkata. “Apart from items to decorate the house, we use terracotta items for daily use. For example, in summer we do not drink cold water from the refrigerator but instead use an earthen terracotta vessel. My mother makes it a point to do a certain fish preparation in spite of it being time consuming, so that she can use the particular terracotta utensil.”

In the urban milieu, the demand for terracotta goods in Kolkata households has reached a saturation point. As the central government actively pushes for the promotion of various handicrafts from different states, art forms of other regions, particularly Madhubani paintings and Rajasthani handicrafts, are certainly very popular. Bankura’s terracotta seems to be lagging behind in this regard.

Bankura’s terracotta is a classic case of a dying cultural heritage. Sustaining the art is a social responsibility. Unlike the rest of West Bengal, the parliamentary constituency of Bankura has voted against incumbent leaders and political parties twice in the last decade, which is a major indication of people’s awareness and urgency of development in the region.

Culture is a matter of recognition, and aesthetics is more about perception than materiality. Very recently, the West Bengal state government has reportedly nominated Bishnupur’s terracotta temples for the UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This should be considered as a massive step toward drawing attention to this part of Bengal’s history and culture. However, only time will tell how efficiently such measures could facilitate the socioeconomic advancement of the potters’ community in Bankura.

(Note: All the pictures used in this article were taken by the author in Bankura District, India, and Munshiganj District in Bangladesh during the surveys.)

Reprinted, with editing, from FIRSTPOST, https://www.firstpost.com/living/bankuras-terracotta-can-timely-measures-facilitate-socio-economic-revival-of-potters-community-7001001.html.