Inspections are playing a growing role in international law as a compliance tool, but they remain underexplored in legal scholarship. Swati Malik (Geneva Graduate Institute, 2020, 2021) used an SRG award to further her comparative analysis of how inspections operate across three international legal regimes.

* * *

My doctoral research at the Geneva Graduate Institute examines the legal basis, authority, and implications of inspections in international law. Inspections, though increasingly relied upon, remain a somewhat underexplored mechanism for ensuring accountability across various global legal regimes. They aim to secure state compliance with international treaties and agreements, particularly in fields like disarmament, environmental governance, and human rights protection.

What motivated me to pursue this research is the growing role inspections play in international law and the relative scarcity of detailed legal scholarship on the subject. While inspections are a powerful tool for verifying whether states adhere to international norms, their legal foundations and operational practices are often taken for granted.

My research seeks to fill this gap by analyzing how inspections operate legally and practically across three international legal regimes—those governed by the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW), and the United Nations Convention Against Torture (UNCAT) and its Optional Protocol (OPCAT).

Conducting Fieldwork in The Hague

The use of inspections as a compliance tool has expanded across different international law regimes, though their methods and frameworks differ significantly based on the context. For instance, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) conducts stringent inspections to verify that state parties to the CWC are fulfilling their obligations to dismantle and destroy chemical weapons.

In contrast, ICRW inspections—mandated by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) but led by the states parties themselves—--focus on ensuring adherence to quotas and regulations designed to balance the conservation of whale species with cultural and economic practices.

Finally, the inspections carried out by the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture (SPT) under OPCAT are vital for ensuring that states comply with human rights standards in relation to the prohibition of torture and inhumane treatment.

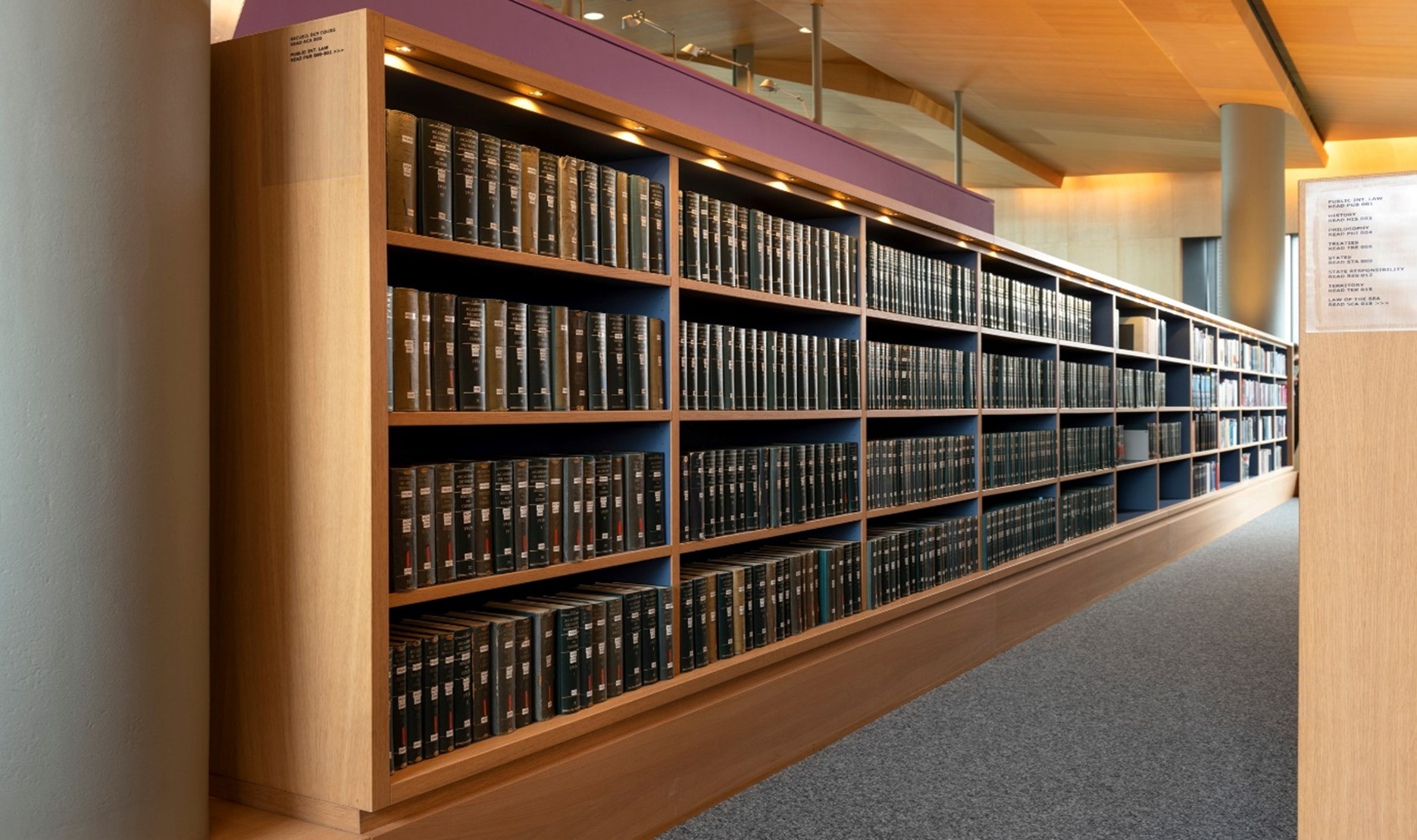

In 2023, I was awarded a Sylff Research Grant, which allowed me to conduct international fieldwork in The Hague, Netherlands. This phase of my research focused on the OPCW’s work and the resources available at the Peace Palace Library, which hosts one of the world's largest collections of international law materials. This opportunity was essential to my comparative analysis of inspections in international law, particularly in understanding how inspections are governed and implemented within the chemical weapons’ disarmament regime.

International Court of Justice, 2024.

Doctrinal and Qualitative Research

My SRG research methodology combined doctrinal analysis with qualitative methods. Doctrinally, I examined the legal framework that underpins inspections in the CWC. This involved analyzing the treaty itself, OPCW reports, and secondary sources related to these inspections. My archival research at the Peace Palace Library also enabled me to access key legal precedents and historical materials that illuminated how the practice of inspections undertaken by the OPCW has evolved over the years.

In addition to doctrinal research, I employed qualitative analysis to better understand the operational challenges of inspections. Due to the confidential nature of OPCW inspections, my research relied heavily on publicly accessible reports and archival materials. These were complemented by informal discussions with legal experts in the field, which allowed me to incorporate both theoretical and practical perspectives into my analysis.

Peace Palace Library Collection, 2024.

Legal Framework and Authority of OPCW Inspections

The inspections conducted by the OPCW are governed by the CWC, a treaty that establishes one of the most comprehensive verification mechanisms in international law. The CWC mandates a tiered inspection regime comprising routine inspections, challenge inspections, and investigations of alleged use, each with distinct protocols designed to balance the imperatives of disarmament verification with the sovereignty of state parties.

While routine inspections assess compliance with declarations regarding chemical facilities, the treaty also provides for challenge inspections, an extraordinary tool theoretically enabling state parties to request intrusive verification of suspected violations. Despite the robust legal framework available to tackle them, no challenge inspection has ever been invoked, underscoring the political and procedural complexities inherent in this mechanism.

My research highlights the nuanced nature of these inspections. Routine inspections, though standardized, vary significantly depending on the type of facility inspected, such as chemical weapon production sites, destruction facilities, or storage locations. Each category is subject to tailored protocols that address the specific risks associated with the chemicals involved.

By contrast, inspections in conflict zones, such as those conducted in Syria, deviate from the routine model. These inspections have required the adaptation of the CWC’s general provisions to circumstances involving active hostilities, access restrictions, and contested political narratives. The legal challenges in these cases illustrate the flexibility and limitations of the OPCW’s mandate, particularly in environments where state consent is precarious or absent.

A critical element of the OPCW’s inspection regime is the treatment of inspection reports. These reports are classified as strictly confidential. This confidentiality is intended to protect sensitive information while ensuring the integrity of the verification process. However, it also raises questions about transparency and accountability, as the specific findings often remain inaccessible to the broader international community.

My archival research demonstrated that the confidentiality of these reports does not preclude their strategic use in shaping state behaviour. States found to be in noncompliance may face significant political and reputational consequences, even in the absence of public disclosure. This dynamic underscores the dual role of OPCW inspections—as a mechanism for technical verification and as an instrument for reinforcing international norms and obligations contained in the CWC.

Challenges in Conducting Inspections

Inspections conducted under the CWC face a range of operational and political challenges; these challenges often arise from the intersection of legal obligations and the geopolitical realities of the states involved. A significant challenge lies in the logistical aspects of inspections, particularly in conflict or high-risk zones.

For example, inspections in Syria have highlighted the difficulties in securing safe and timely access to facilities. Inspectors must navigate not only the physical risks associated with active conflict but also restricted access imposed by states citing security concerns or administrative delays. Such restrictions can affect the thoroughness of inspections and raise questions about the comprehensiveness of their findings.

Political interference and influence represent another pervasive obstacle. While the CWC provides legal backing for challenge inspections, the political cost of invoking such a measure has deterred states from exercising this option. The absence of challenge inspections to date underscores the diplomatic sensitivities surrounding their implementation.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed vulnerabilities in the OPCW’s verification processes by necessitating a significant shift in inspection methodologies. With travel restrictions and health risks limiting in-person activities, the OPCW transitioned many aspects of its routine inspections to online platforms. Remote verification measures, such as virtual inspections and the submission of digital documentation, were adopted as solutions to maintain compliance monitoring. While these measures allowed the OPCW to continue its work during unprecedented circumstances, they also highlighted the limitations of online methodologies in tasks requiring physical oversight, such as sample collection and on-site verification of equipment. This shift underscored the importance of balancing technological adaptability with the rigorous standards expected in international verification regimes.

In my research, I also noted the importance of the OPCW’s procedural flexibility to address challenges systematically. Its frameworks, while robust, rely heavily on the preparedness and expertise of inspection teams to navigate unforeseen circumstances, such as sudden shifts in geopolitical dynamics or emergency situations. This adaptability is a hallmark of the OPCW’s operational effectiveness as it ensures that inspections remain credible even under challenging conditions.

Routine inspections are the backbone of the OPCW’s mission to uphold the CWC’s principles. While logistical, technical, and operational challenges are inherent to the process, they underscore the resilience and adaptability of the verification regime. My research highlighted the need for continued refinement of protocols and greater investment in tools and strategies that enhance the OPCW’s ability to conduct inspections under varying circumstances, ensuring their long-term effectiveness.

Societal Contributions and Impact

The findings from my research contribute to a deeper understanding of how inspections function as mechanisms for accountability and compliance in international law. By examining inspections across different legal regimes, my work highlights their importance in maintaining global security, promoting environmental conservation, and safeguarding human rights.

In the case of the OPCW, inspections have played a crucial role in eliminating the global stockpile of declared chemical weapons, thus contributing to international peace and security. The inspections conducted under the ICRW, on the other hand, help preserve endangered whale species by ensuring that states comply with conservation quotas while recognizing cultural and economic needs. Meanwhile, the SPT inspections help prevent and address torture and inhumane treatment by holding states accountable to their human rights obligations in this realm.

The societal contributions of inspections go beyond their immediate legal context. They promote transparency, foster cooperation between states, and provide mechanisms for peacefully resolving disputes. In doing so, inspections contribute to a more stable and predictable international order, where states are held accountable and international norms are upheld.

Universality and Diversity of the Human Condition

Inspections, as a legal mechanism, reflect both the universality and diversity of the human condition. On one level, inspections are grounded in universal principles of accountability, transparency, and rule of law. They represent the collective interest of the international community in ensuring that states adhere to their legal obligations, whether in the areas of disarmament, environmental governance, or human rights.

At the same time, inspections must be adapted to the specific legal, political, and cultural contexts in which they are conducted. Inspections within the disarmament regime differ significantly from those in human rights or environmental governance reflecting the diversity of the international legal landscape. This flexibility is a testament to the adaptability of inspections as a legal tool and underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of how inspections function across different contexts.

Conclusion and Future Research

The SRG award has been invaluable in advancing my research on inspections in international law. The fieldwork conducted in The Hague allowed me to access critical resources and better understand the OPCW’s role in enforcing compliance with the CWC. This phase of my research provided a solid foundation for the next stage of my project, which will focus on inspections under the IWC regime.

Moving forward, I plan to complete my fieldwork at the IWC Secretariat in the United Kingdom. By studying the Secretariat’s inspection reports and interacting with experts, I aim to finalize my comparative analysis of inspections across the three legal regimes. This analysis, I hope, will provide a comprehensive understanding of the legal basis, authority, and implications of inspections in international law and also hopefully contribute to both academic discourse and practical policymaking in international law.

The main sources of my SRG research were the OPCW Archives in The Hague and a variety of academic materials related to OPCW inspections found at the Peace Palace Library, also in The Hague.