Naglaa Fathi Mahmoud-Hussein, a 2015 Sylff fellow at Howard University in the United States, implemented a social project for women handcraft artists in Nubia, Egypt, under the Sylff Leadership Initiatives (SLI) program from mid-June to September 2016. The three-month project, comprising field interviews, workshops, and a training program, helped these women get educated on financial knowledge and skills. More importantly, the women are now aware of the value of their artistic pieces and how they should be fairly evaluated.

* * *

Motivation behind the Project

Women in the Middle East and Africa share a common history and cause. In both regions, women played active roles in resisting and recovering from the colonial trauma. In postcolonial times, however, the perceptions of African and Middle Eastern women and their role in development have often been underrepresented. Women handcrafters, for example, are considered merely producers of unsubstantial commodities—goods that add little to the economic empowerment of nations. The artistic production of those women is seldom acknowledged as art that should be nurtured and included in the art scene, which defines the scopes of cultural identities of these societies. As a case in point, Egyptian Nubian women handcrafters do not enjoy the ranking status of artists whose work is based in Cairo workshops, studios, and exhibitions. Hence, it is important to reach out to those women.

Nubian women handcrafters are now navigating different facets of their identity complexes. Already placed on the periphery and being darker skinned, residing mainly in the villages on the border between Egypt and Sudan, Nubian women are negotiating their blackness, their gender dynamics, and state policies toward their artistic productions.

During the time of Hosni Mubarak (1981–2011), Nubian women handcrafters depended heavily on the trading of their artistic productions during seasons of high tourist influx in Egypt. However, the political unrest in recent years has greatly impacted the influx of tourists to Nubian villages. Moreover, new state legislations restricting civil society work have resulted in a shortage and even lack of funding to these women.

For example, on November 28, 2016, the Egyptian parliament approved a new restrictive draft law to govern civil society organizations. The draft includes provisions that require permission from the government before civil society organizations (CSOs) can accept foreign funding; require government permission before foreign CSOs can operate in Egypt; require government permission before CSOs can in any way work with foreign organizations or foreign experts; limit CSOs’ activities by requiring government permission to conduct surveys or publish reports; raise the fee for CSO registration and give the government broad discretion to refuse to register a CSO; and heighten the penalties for violations of the law to include prison sentences and steep fines.

The main objective of my project was to contribute to the empowerment of rural Nubian women artists by helping women to run small businesses and providing them with the necessary skills needed to establish and effectively run their businesses. Secondly, I hoped to create a sustainable instrument that provides Nubian women with economic consultations and support. Finally, my project’s overall endeavor was, and still is, to preserve and promote Nubian artistic handicrafts.

The Project

Field Interviews

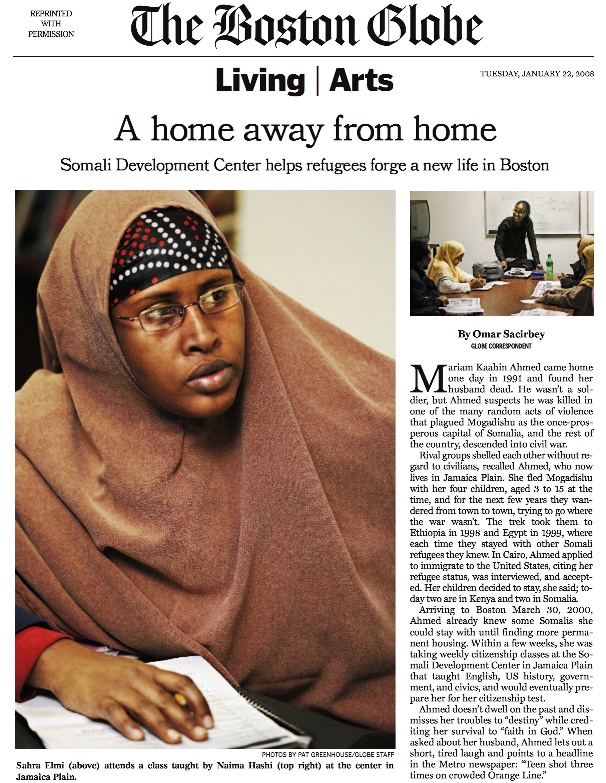

In my field interviews, I focused on underscoring key challenges that face women running small businesses as articulated by the interviewees. Thirty women were interviewed.

Based on the field interviews, which were also documented on video, I found that women owning small businesses in Aswan suffered from several problems including the lack of marketing and promotion skills, inability to perform simple accounting tasks, and lack of knowledge on loans institutions, on how to carry out feasibility studies for their projects, and on the registration and taxation process. Most of the women whom I interviewed had never participated in art exhibitions, lacking the means to reach out to the exhibition organizers. Most interviewees welcomed the idea of establishing economic consultation centers (ECU) that provide economic consultation to women owning small businesses.

Training of Trainers Program

I then organized a Training of Trainers (TOT) program from July 26 to 28, 2016, in the Aswan governorate. The training brought together 15 young educated women with relevant university degrees to become economic consultants who can provide capacity building for women running small business. The target trainees were selected based on their education, their willingness to volunteer and continue to provide business consultation for women, and their geographic location. Participating women cadres gained TOT skills, consultation providing skills, small business accounting skills, and various outlets for obtaining small business loans. The training included practical exercises, such as simulations in which the trainees played the roles of a consultant and a woman seeking a specific business consultation. The trainees worked to design and produce a blueprint of the proposed training lessons, which they will be using to train women who run small businesses.

Women Training Workshops

There is no question that the above-mentioned legislations will hinder efforts to reach out to women handcrafters through systematic work with grassroots or civil society. In an attempt to open up a way forward for these women artists, I traveled during the summer of 2016 with the support of a Sylff Leadership Initiatives (SLI) grant to conduct two workshops to help Nubian women handcrafters find a platform for economic support. The two workshops saw the participation of 30 women running small businesses and provided these women with small business skills such as identifying business opportunities, business development, administrative skills, basic accounting, managing credits, and loans skills. The women received training on how to develop and refine their products for better marketing and on how to identify wholesalers and develop a commercial network. They also learned about how to outreach and participate in art exhibitions in and outside the governorate of Aswan.

Economic Consultation Units

Trainees who underwent the TOT program and those who have been trained in economic consultation skills work in coordination with partner NGOs in Aswan to provide free consultation. The contact information for the consultants were disseminated among women running small businesses during the training. The women regularly contact the consultants by phone, and in many instances they request a meeting, which then usually takes place either at the premises of a partner NGO or at the consultant’s place.

Outcomes

Trainees participating in the workshops acquired new skills including project management and marketing skills. They learned about the role of the Ministry of Social Solidarity in supporting the small business sector, the various forms of technical and financial assistance provided by the ministry, and means of approaching the ministry. The Nubian women gained information about various financial and lending institutions and the necessary procedures to apply for loans with such institutions as Nasser Bank, the Social Fund for Development, and NGOs working in the field of small projects. In addition, they learned how to carry out bookkeeping and use simple accounting methods to manage the financial side of their projects.

In conclusion, the three-month project helped raise the aspirations of these women to develop, promote, and market their small businesses. The impact that workshops like these have on women handcrafters’ businesses makes it essential to hold such trainings frequently.

Despite any difficulties that researchers and members of civil society may be stumbling across, they are looking at the future of social activism through artistic work with enthusiasm, devotion, and commitment.

Details can be found at http://tamkeen.webs.com.