Opened in 1991, the Dadaab refugee camps in northeastern Kenya have seen two generations of Somali refugees born or grow up within their confines. According to 2016–19 Sylff fellow Mohamed Duale, who conducted his PhD research there, protracted refugee situations like this have become increasingly common. But the West’s recent response to Ukrainian refugees suggests that there is more to the story than the Global North’s professed inadequate capacity to resettle refugees, says Duale.

* * *

In by-gone times, forced displacement was considered a short-term emergency. In recent decades, displacement has taken an increasingly protracted nature as contemporary wars have lingered for many years, sometimes decades. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), also known as the UN Refugee Agency, explains that “protracted refugee situations are those in which at least 25,000 refugees from the same country have been living in exile for more than five consecutive years.”[1] It estimated in 2018 that “78% of all refugees are in protracted refugee situations.”[2] About 85% of the 20.8 million refugees registered with the UNHCR in 2021 lived near their countries of origin in the Global South.[3] UNHCR policy recognizes three durable solutions to forced migration: resettlement to a third country, local integration in the host country, and voluntary repatriation to the country of origin.[4]

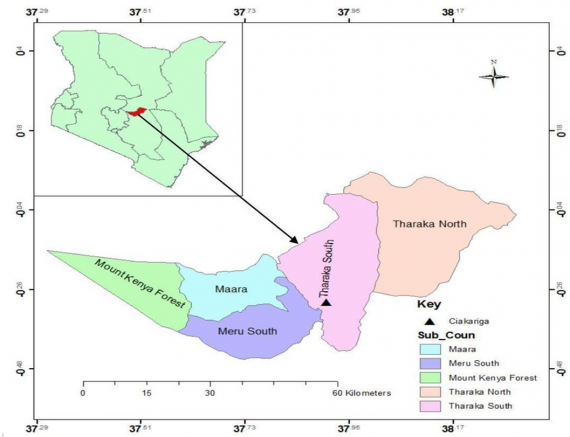

I did my PhD research on Somali refugee youth in the Dadaab refugee camps of northeastern Kenya, one of the world’s largest and longest sites of protracted displacement. Since opening in 1991, two generations of Somali refugees were born or grew up in the Dadaab camps under harsh social, economic, and political conditions. Somali refugees have historically been seen as a thorn in the side of the Kenyan state, especially as it battled the Somalia-based Al-Shabaab extremist group in recent years. The Dadaab camps were unfairly blamed as harbouring terrorists, and in 2013 Kenya concluded a tripartite agreement with Somalia and the UNHCR to close them.[5] As Somali refugees are predominantly Muslim, the global war on terror has stigmatized and deleteriously impacted their resettlement in the Global North. Today, most Somali refugees in Kenya find themselves confined to refugee camps and deprived of relocation to a third country with an indeterminable return to their conflict-affected homeland. Refugees in other parts of Africa and much of the Global South find themselves in similar situations of being stuck in displacement and facing an uncertain future.

A refugee camp in Dadaab. (Photo by Nichole Sobecki/GroundTruth, source: The GroundTruth Project https://thegroundtruthproject.org/somalia-conflict-climate-change/reportage_sobecki073/)

Young people living in the difficult social milieu of refugee camps are particularly interesting to me considering their simultaneous vulnerability and resilience. Though categories of youth vary among agencies and governments, figures suggest that young people constitute most refugees in the world. For example, 51% of refugees are thought to be under 18 years of age, 33% between 10 and 24 years old, and 35% between 15 and 24 years old.[6] Despite their demographic majority, refugee youth have sometimes been called an “invisible population.”[7] Nevertheless, there is no shortage of ambition among refugee youth living in protracted displacement. Sagaro, a young Somali refugee man in the Dadaab camps, recalled: “I was born in this camp nineteen years ago. At the age of twelve, I had to leave school to start my own business to feed my family. . . . I must succeed and become rich. I want to become a big businessman. But for now, I don’t have a lot of money, so I will continue to work hard until I do.”[8]

As I previously argued elsewhere, global refugee policies discuss refugee youth based on the neoliberal precepts of self-reliance.[9] Global refugee policies also seek to contain refugees to their regions of origin in the Global South, mostly in neighboring countries where 73% of the world’s refugees reside.[10] For Somali refugees in Kenya, host state and international refugee policies have narrowed access to local integration and resettlement whilst encouraging voluntary repatriation to their home country. Given ongoing instability in Somalia, young Somali refugees in the Dadaab refugee camps find themselves without the usual rights of civilian life. Jamale, a young Somali refugee man in Dadaab, explained a few years ago that “[Not] many countries are welcoming refugees and migrants because they don’t see refugees as normal human beings. They may see you as a terrorist or as a beggar. What can I do to change that narrative? What can I do [for] people to allow me to realize my dreams?”[11]

Global North states, as powerful actors in the international refugee regime, increasingly prefer to keep African and other racialized refugees in refugee camps in Global South countries, possibly condemning them to decades, even a lifetime, of displacement and obscurity.[12] The West’s positive response to the recent refugee movement from Ukraine has for critical observers upended Global North self-narratives of inadequate capacity to resettle refugees and donor fatigue regarding so-called refugee crises. These supposed lacks and lethargies may have been smoke screens for more nefarious shortcomings: the undesirability and disposability of racialized refugees in Global North politics. Most refugees are from the Global South and are thus mainly people of color. Sequestering them in refugee camps is neither just nor politically tenable if humanity is to forge a shared future in the aftermath of centuries of colonialism. For the most part, young Somali refugees must largely rely on themselves to find their own durable solutions, learning for and building a better future that is yet unknown. But surviving the social stagnation of protracted displacement is not a struggle that individual refugee youth should have to wage alone; the odds are stacked against them. If states in the Global North are abandoning their obligations to African and other racialized refugees, civil society in these countries must—if they desire a common future with the rest of the world—show refugee youth, and all refugees, living in protracted displacement in Kenya and elsewhere in the Global South the concern and solidarity they have so rightly given Ukrainian refugees.

[1] “Protracted Refugee Situations Explained,” USA for UNHCR, January 28, 2020, https://www.unrefugees.org/news/protracted-refugee-situations-explained/.

[2] “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2018,” UNHCR, June 20, 2019, https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2018/.

[3] “Refugee Data Finder,” UNHCR, updated June 16, 2022, https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

[4] UNHCR. (2003, May 1). Framework for Durable Solutions for Refugees and Persons of Concern. UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency. https://www.unhcr.org/partners/partners/3f1408764/framework-durable-solutions-refugees-persons-concern.html

[5] S. Allison, “World’s Largest Refugee Camp Scapegoated in Wake of Garissa Attack,” The Guardian, April 14, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/14/kenya-garissa-dadaab-scapegoat-al-shabaab.

[6] E. A. Marshall, T. Roche, E. Comeau, J. Taknint, K. Butler, E. Pringle, J. Cumming, E. Hagestedt, L. Deringer, and V. Skrzypczynski, Refugee Youth: Good Practices in Urban Resettlement Contexts (Victoria, BC: Centre for Youth and Society, University of Victoria, 2016).

[7] Marshall et al., Refugee Youth.

[8] “Dadaab: Growing up in the world’s largest refugee camp,” report by M. Guiheux, France 24 English, January 7, 2017, https://youtu.be/LE6H0GGWrq8.

[9] M. Duale, “‘To Be a Refugee, It’s Like to Be without Your Arms, Legs’: A Narrative Inquiry into Refugee Participation in Kakuma Refugee Camp and Nairobi, Kenya,” Local Engagement Refugee Research Network, May 5, 2020, https://carleton.ca/lerrn/2020/to-be-a-refugee-its-like-to-be-without-your-arms-legs-a-narrative-inquiry-into-refugee-participation-in-kakuma-refugee-camp-and-nairobi-kenya/.

[10] “Refugee Data Finder,” UNHCR.

[11] AJ Plus, “Finding Hope in Africa’s Largest Refugee Camp,” December 10, 2019, https://youtu.be/61VLuz5e0co.

[12] M. Dathan, “Home Office Anger over ‘Racist’ Rwanda Policy,” The Sunday Times April 22, 2022, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/home-office-anger-over-racist-rwanda-policy-vp8gzbw2q; and O. M. Osman, “The Somali Refugees Whose Lives Were Halted by Trump’s Travel Ban,” Al-Jazeera, July 2, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2019/7/2/the-somali-refugees-whose-lives-were-halted-by-trumps-travel-ban.