Julia Orosz, a 2019 Sylff fellow at the University of Debrecen (Hungarian Academy of Sciences), focuses on the situation of Hungarian women in Transcarpathia in the post–World War II communist era in her PhD dissertation. She has been dealing with this topic for many years, and as a Sylff fellow she has broadened her basic research topic by examining the connections and differences between the circumstances and opportunities of women living in the communist era, comparing it with the position of today’s young girls in the fields of further education, women’s work, career development, family formation, and childbirth. In this article, she gives a little insight into the lives of women living in the communist era.

* * *

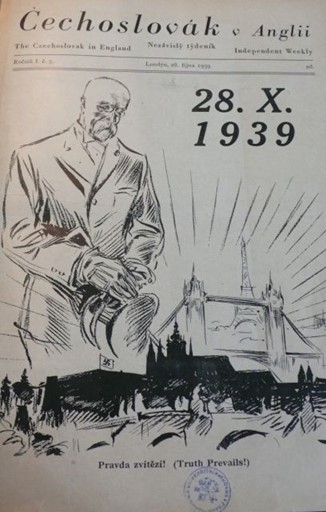

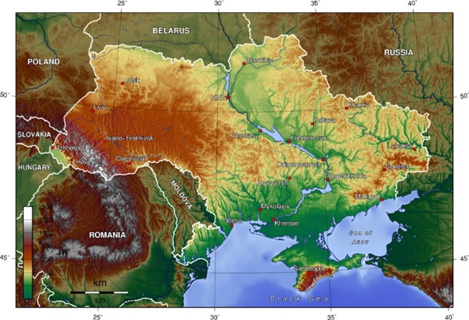

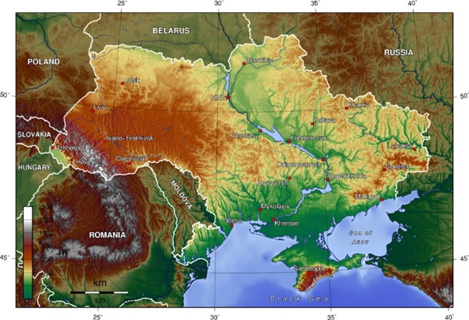

Transcarpathia has been the westernmost region of independent Ukraine since 1991, bordering four countries (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania). It currently covers an area of 12,752 square kilometers. Transcarpathia’s twentieth-century history is extremely versatile, as it has undergone several changes of empire. Under the 1920 Trianon Treaty, the area was separated from Hungary and came under Czechoslovakia’s control. Due to the border revision goals of Hungarian foreign policy and the First and Second Vienna Awards (1938 and 1940), by the time of World War II (1939–1945) the separated territories were returned to the motherland, but the outcome of the world war again changed this. By virtue of the Soviet-Czechoslovak Convention signed on June 29, 1945, the region became part of the Soviet Union, and the decree of the presidency of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union of January 22, 1946, declared it to be the Transcarpathian territory of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[2] Transcarpathia was thus put into the mold of communism, as were all countries undergoing or forced into socialist development, which influenced the political, economic, and social life of the region.

Topographic map of Ukraine. Transcarpathia is located in the western part of the country, with the regional headquarters in Uzhhorod. (Source: https://www.prntr.com/ukraine-map.html)

I chose Transcarpathia for my study for two reasons: firstly, it is my motherland and I am interested in the history of my ancestors, and secondly, due to its location and nationality, Transcarpathia is a specific area that connects the East with the West. Although Ukraine has not had an official census since 2001, recent estimates put the population of Hungarians in Transcarpathia at 120,000–130,000. In 1941 the Hungarian population was 233,840, but according to the 1946 county census (which is not an official census), the number of Hungarians had dropped significantly to 66,000 by that year.[4] This decline in population is mainly explained by the high death toll on the fronts, the mass escape, and the abduction of Hungarian men to Soviet labor camps (the Malenki Robot) in 1944.[5] All of these contributed to the decline in the male population and the transformation of female roles. In many cases, women were forced to take over the place of men and to manage the family alone. In addition, government policy on women contributed to the transformation of women’s roles.

The Stalin Constitution of 1936 stated that women should enjoy equal rights with men in all areas of life. A well-built network of propaganda sought to emphasize to people that communism had led to the breakdown of decades of barriers and the opening of opportunities for women. As an era, I deal with the period from 1944–45 to the 1950s, as the 1950s are the most characteristic and most dictatorial chapter of the communist regime. In the Stalin era, the new female ideal was the stanovist top worker, someone who excelled at her workplace and was able to cope with more difficult physical jobs, even masculine ones, and this was the example to follow.[6] It was the responsibility of the press to promote it, so it should not be surprising that women workers in a wide variety of fields became frequent figures in the newspapers. Of course, these reports could only glorify the communist power and the opportunities offered by the system.

One example among many is Etelka Bálint, a former kolkhozist at the Lenin kolkhoz[7] in Bereg. Etelka said: “During the capitalist rule, I had no goals. My life was miserable, I worked for kulaks.[8] But the situation changed in the years of the Soviet system. I was given freedom. I entered the kolkhoz. I am provided with annual bread, and as a team leader and as a board member I take part in managing the kolkhoz. As a simple working woman, I was given leadership and the right to freedom and happiness.”[9] In 1948, she was honored with the Order of the Red Flag of Work for high grape yield.[10] The Soviet government was also keen to reward women with various honors, such as the Lenin Order, Red Flag Order, and Socialist Labor Hero, to emphasize their merits to the state and society. The party leadership wanted to prove that, regardless of their social status and qualifications, women who work and are committed to the development of the country are rewarded.

The active builders of communism. Top half, left to right: Margit Katkó, leader of the group for the Rimavské Janovce Vineyard, Socialist Labor Hero, Lenin Order–honored worker; Ilona Kosztel, burner of the Berehovo brick factory; and Gizella Titka, a stanovist at the furniture factory in Berehovo. Bottom half, left to right: Maria Hrobák, commander of the Kalinin kolkhoz in Berehovo, recipient of the Lenin Order; Malvin Kovács, brigade commander of the Berehovo garment factory; and Maria Papp, group leader for the Muzsajj Vineyard, recipient of the Order of the Red Banner of Labor.[11]

However, there are some differences between the portrayal and idealization of women by the communist party leadership and the real, everyday life of women. As there are few written sources about women’s daily lives and activities, and what is to be found was produced under very strong ideological pressure and censorship, I have sought to supplement archival sources and contemporary press publications with reminiscences. Today, we are fortunate enough to be able to visit people who have lived during the socialist era and, through their personal experiences, gain interesting information that is not always evident from archival materials and official documents. This not only gives us a more complex picture of the era, but also allows us to interpret and understand people’s lives.

The author, right, with an interviewee.

After 1945, the major turning point in gender roles worldwide was the influx of women into paid employment,[12] which of course does not mean that women had not worked before. In the socialist countries, the state tried to treat the mass employment of women as an achievement of equality, whereas the real reasons were the difficulty of living, the postwar labor shortage, and the need for employment. Because of low wages, a single salary was not enough to support families, and because of the state’s extensive economic policy and strong industrialization, it was necessary to employ every person of working age, so that more women could be employed.

My informants are simple, ordinary women, born in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. They come from peasant families with many children, where the father was the breadwinner and the mother worked in the household. As children and young girls, they lived through World War II and its effects. Because of a lack of opportunity, they have a low level of education, and most of them were employed as farm workers in the kolkhozes or in various branches of industry.

Transcarpathia was a strongly agricultural region. With the sovietization of the area, individual and private farming was abolished and the so-called kolkhozes appeared, providing the only job opportunities in the villages. Stalin considered it important to actively involve women in socialist production: “The issue of women in kolkhozes . . . is an important question, comrades. I know that many of you underestimate women. . . . However, this is a mistake. . . . It is not only about half of the population being women. First and foremost, the kolkhoz movement has raised many outstanding and talented women to leadership positions. . . . Women have long since risen to the forefront from previously lagging behind. In kolkhozes, women represent great power. Keeping this power under restrictions . . . is a sin.”

Agricultural girl group, Szernye. Róza S. is on the right in the middle row.

One of my interviewees, Róza S., was born in 1933 in Serne.[14] Her father was a farmer who died in 1944 as a soldier of the Hungarian army, and her mother raised three children as a widow. Róza spoke with poignant sincerity about their daily problems: “My mother would go out to the meadow and climb the tree. From there she would cut off the dry branches, tie them, and bring them home on her back so that the three kids would not freeze.” Róza had a difficult childhood, so she only completed five classes, plus one repetition. At a very young age, she was already working as a farm worker in the kolkhoz. “I was a very good student. They [her two older brothers, Janos (born 1928) and Balázs (born 1930)] persuaded me to go to school if they couldn’t; at least I would be able learn and go to school. I did not go; I chose to work. . . . I was fourteen, and I went to work on the field. . . . We carried the bobbins together. Well, by the same time the next year everyone had become a worker at the kolkhoz [in Serne, which was formed in 1947). Life became very, very difficult. . . . They took our land, and everyone was forced to work there. They did not ask if you wanted to give up your land. Some resisted. Their land was sown in the spring, and it was harvested by the kolkhoz in the autumn.” My interviewee was a milkmaid, a farm worker in her youth, and went to work at the kolkhoz tobacco plantations. “Every day we went to plow, we went barefoot, we didn’t have slippers like that. . . . Back then, it wasn’t really machine plowing, just hand plowing.” In 1955 Róza, as a group leader, was able to represent a group of local kolkhoz girls at a Moscow agricultural exhibition as a result of her abundant crop yield. “I even went to Moscow for an agricultural exhibition. They took me from the kolkhoz because I was a group leader. We were girls, only girls. We had a good crop of beets, we had beets that weighted ten kilos. Well then, they got me out there.”

Roza S., fourth from left, as a milkmaid.

Roza S., front row center, in Moscow, 1955.

Similarly, Jolán B. had no easy youth.[15] Born in 1943, Jolán had seven siblings. They lost their mother early, and she was fifteen years old when her mother’s duties fell on her. (As her four older brothers were already married, she had to care for her two younger brothers, born 1945 and 1947, and her younger sister, who was ten years younger than her, having been born in1953).

Jolán B. working on the hen farm.

“One would go to school in the morning in boots and come home at noon, then the other would go to school in the same boots. This was our life. . . . For my sister, I was able to alter what I had outgrown.” Jolán worked at the kolkhoz for 30 years: 8 years on the hen farm and the rest on the vegetable-producing brigade.

There were also many women in Transcarpathia who were placed in higher leadership positions by the party leadership. Such was the case of Jolán Antal, president of the Marx kolkhoz in the village of Szolovka. The kolkhoz was formed on October 11, 1947, with the participation of 16 families, and by August 21, 1948, the peasantry of the whole village had joined. The president gushed about the greatness of the kolkhoz system: “All our hard work is done by machine, and this year we have been harvesting with a combine. As a result of Soviet agro-technology and well-organized joint management, the land gives twice as much as it used to before to individual farmers. . . . As the kolkhoz grows, people can live in a better way. Of course, it was difficult for us in the beginning. But we’ve gotten over it. No one would replace his present life with his old life. After the poverty, prosperity and post-oppression freedom came.”[16] Other individuals who have gone through the era remember things a little differently. Erzsébet B., a 1931-born resident of Velyka Dobron, recalled: “The Russians came in, took the land, cleaned out everything, took away all the animals. . . . I was still a girl when the kolkhoz was formed [in 1949]. We went to the field. . . . We had to hoe cabbage, potatoes, everything with a hand hoe; we had to break the corn by hand. . . . In the winter we only went to do tobacco. . . . They didn’t pay us a salary, just the norm. . . . It was very little, but back then everything was cheap.”[17]

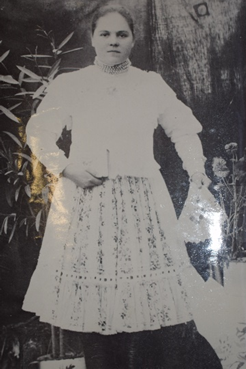

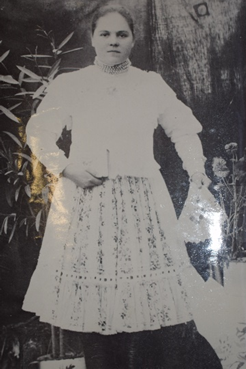

Erzsébet B. at the age of 14 in Nagydobony folk costume.

In the 1950s, women were welcomed to work where previously only men worked. Many were engaged in heavy industry, construction, mining, turning lathes, and welding, but the greatest spotlight of the era was given to the women operating tractors. According to historian Zsófia Eszter Tóth, they wanted to symbolize that women are completely equal to men and that they are capable of the same performance in any job.[18] As the tractor operating industry was not very attractive to women, all means of propaganda had to be used to promote the profession, such as Soviet role models like Pasa Angelina, articles, movies, posters, brochures, songs, and poems. While studying the press, I found that there were quite a few women in Transcarpathia who had completed courses at the Machine and Tractor Station and worked on a tractor, but there was no published information indicating that most of them were forced to do so. “We are proud to be the first tractor operating women in Transcarpathia. We all follow the shining example of Pasa Angelina, known worldwide for her work victories. None of us would have thought yesterday that we girls and women would master the tractor operating profession.”[19] So said Sarolta Szalontai, the female brigade commander of the Rákosi GTC. Most of my 32 interviewees so far worked in various kolkhozes in Transcarpathia, and they recalled that it was not common for women to be tractor drivers; they know or have heard about singular cases, but for some reason women were forced to do so and only temporarily.

According to my interviewee Jolán B., her sister-in-law Gizella Szijjártó, the wife of her eldest brother, drove a tractor: “My sister-in-law lived in Heivtsi,[20] and when she was a girl, her father was a kulak. . . . They were treated very strictly. When her father was taken away as a kulak to Donbas,[21] they wanted to take my sister-in-law also, so she had to enroll in a tractor driver course in order to not be taken away. There was a school here in Dobrony where girls also went, and my sister-in-law worked on a chain tractor. . . . Not for long, but she worked . . . to not be taken to Donbas.”

Over the centuries, women’s roles have also constantly evolved. In traditional society, women’s primary tasks were childbirth and parenting, along with running a household and caring for the family. Their activities were mainly confined to the home. In the twentieth century, significant changes took place in this area. With the influx of women into paid employment, they faced the problem of double burden bearing. It was not easy for women in the 1950s. Working women were given only six weeks’ maternity leave before childbirth and after. In reality, however, this did not really make life easier for young mothers.

As Gizella D. (born 1941) and Gizella T. (born 1942) shared with me: “The decret [maternity leave] lasted for two months before and two months after. Four months off. We got two hours for breastfeeding a day, so we could go home and breastfeed, and then we had to go back. . . . We also washed the diapers. . . . We had no pampers [disposable diapers] as we do now. Today’s world cannot be compared to [those days].”[23] In order for women to be able to work with young children, the state had to ensure that the children were properly accommodated. In the 1950s kindergartens opened, and even seasonal nurseries were organized in Transcarpathia for farm laborers. But places were limited, so many women could only work if their children were with the older generation at home, and many grandparents helped with child-rearing. Jolán B. talked about the problem of women’s dual burdens: “I almost went into labor on the farm. I worked up until December 25 and went to the hospital on January 1. . . . Then my mother-in-law agreed to take the boy, so I went back when he was two years old. . . . The kindergarten only accommodated twenty-five children.” Jolán Sz., who was born in 1937, had a similar story: “Even the day before giving birth, I was in the kolkhoz. After I gave birth at night, I didn’t go for a month. My mother-in-law looked after the little girl. Then when my son, Sanyi, was born on January 1, I was back at work by February. . . . Only twenty children were admitted to kindergarten in such a large village, so I tried to get a place for them in vain; there were none.”[24]

In addition, it is important to bear in mind that households were not at all mechanized. They were lacking the most basic household appliances (such as refrigerators and washing machines), without which we could not imagine our lives today, and which make it easier to do household work. “When we butchered the pigs, as there were no refrigerators, we would lower the meat into the well, where it was cold,” recalled Erzsébet. B. The washing was also done by hand. According to Emma K., born in 1935: “When we bought our first washing machine, in 1968 or when it came to fashion, maybe 1970 . . . we were so happy, but we had to bring the water in and warm it, and then take it back out. But that was good too.”[25] Not everything was available in grocery and clothing stores. “I remember we went to the mountain to work. Easter came, and we were seven girls in a group. . . . We went from Popovo to the mountan in Koson on foot, we worked all day and then went home on foot in the evening. . . . There was a black shop . . . [where] sometimes there was a little sugar. Then we went in . . . and asked Uncle Samu [the shopkeeper] to give us some sugar. He says there isn’t any. Uncle Miska [chairman of the local cooperative] comes and says, what’s up girls? We told him that Easter is here but we don’t have a single piece of sugar, not even for a small milk bread. . . . He says to Samu to weigh half a kilo of sugar for every girl. . . . We lived that way.”

The long decades of the communist era have transformed the structure of Transcarpathia and destroyed the well-functioning peasant lifestyle. Over the years the local population has grown accustomed to and adapted to the new regime, which has become embedded in people’s daily lives. There are many similarities in my interviewees’ life histories and opinions about the era. They were simple, conservative female workers, representing a traditional family model. They have undergone several regime changes, and they vividly remember the tragedy of World War II and the process of collectivization. Their stories can make us feel as though we are hearing the stories of the same people about their difficult postwar lives, their everyday lives, and the opportunities available to them as citizens of the Soviet Union.

[1] József Molnár and István D. Molnár, Population and Hungarians of Transcarpathia in the light of the census and population data, (Berehovo, 2005), 8.

[2] Oficinszkij Roman, “Transcarpathian Ukraine, 1944–1946,” in Transcarpathia 1919–2009: History, Politics, Culture, ed. Csilla Fedinec and Mikola Vehes (Budapest, Argumentum: MTA Institute for Ethnic-National Minority Research, 2010), 233, 243.

[3] Patrik Tátrai et al., “Impact of migration processes on the number of Hungarians in Transcarpathia,” Engravings 7, no. 1 (2018): 26.

[4] Molnár and Molnár, Population of Transcarpathia, 9.

[5] Molnár and Molnár, Population of Transcarpathia, 11.

[6] Mária Schadt, “Emerging working woman,” Women in the fifties (Pécs, 2003), 13.

[7] Kolkhoz: a collective farm or agricultural cooperative of the Soviet Union.

[8] Kulak: an affluent, large-scale farmer. Kulaks have been called out by communism as enemies of the people.

[9] “What the Soviet government did,” Soviet Village 1, no. 47 (October 4, 1950).

[10] “Our kolkhoz star workers: Etelka Bálint Aladárovná is the group leader of the Lenin kolkhoz,” Soviet Village 1, no. 16 (June 17, 1950): 2.

[11] “The active builders of communism,” Red Flag 6, no. 20 (450) (March 9, 1950): 3.

[12] Victor R. Fuchs, On economic inequalities between the sexes (Budapest: National Textbook Publisher, 2003), 28.

[13] Joseph Stalin, from a speech at the first congress of top collective kolkhoz peasants. In Lenin-Stalin: Party and party building, Collection of Lenin and Stalin (Szikra, Budapest: 1950), 655.

[14] Interviewed in Batiovo on April 22, 2015. Róza’s native village, Serne, is located in the Transcarpathian region of Mukachevo, Ukraine. It is situated 20 km southwest of Mukachevo on the banks of the Serne stream.

[15] Interviewed in Velyka Dobron on October 27, 2019. Jolán’s native village, Velyka Dobron, is located in the Uzhhorod region and is the biggest Hungarian-speaking village.

[16] Katalin Osvát, “Two Hungarian kolkhoz peasant women from the Soviet Carpathia,” Women's Magazine 2, no. 40 (October 5, 1950).

[17] Interviewed in Velyka Dobron on December 9, 2019.

[18] Eszter Zsófia Tóth, Daughters of Kádár: Women in the socialist period (Budapest: Open Book Workshop, 2010), 58.

[19] Victory of Stalin 2, no. 21 (62) (Mar. 14, 1951).

[20] Velyki and Mali Heivtsi are located in Transcarpathia, 17–18 km from Uzhhorod.

[21] Donbass: an abbreviation referring to the Donetsk coal basin, an industrial region of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine.

[22] KTÁL. Fond. P-14, opisz 1., od. zb. 737. 8.

[23] Interviewed in Batiovo on July 24, 2015.

[24] Interviewed in Velyka Dobron on February 9, 2017.

[25] Interviewed in Batiovo on December 14, 2016.