Efforts to co-govern the Hauraki Gulf in Aotearoa (New Zealand) through Indigenous frameworks is facing political pushback. Dara Craig (University of Oregon, 2023) explores what it means to govern with—not over—a living marine ancestor.

* * *

Amidst global calls to reimagine governance through Indigenous and relational frameworks, Aotearoa (New Zealand) released a landmark marine spatial plan for Tīkapa Moana (the Hauraki Gulf), a nationally treasured marine ecosystem with her own mauri (life force) and meaning (Sea Change 2017). Despite its promise and widespread support, the plan has stalled, existing opposition has amplified, and the cultural and ecological health of Tīkapa Moana continues to decline (Hauraki Gulf Forum 2023).

My SRG project began with a guiding question: what might it mean to engage Tīkapa Moana not solely as a site of governance but as a living co-governor—a third party to be learned from, managed with, and restored to rightful relationship?

Sunset on Te-Motu-Arai-Roa (Waiheke Island), a motu (island) in Tīkapa Moana.

Tīkapa Moana is home to over one-third of Aotearoa’s residents and is central to whakapapa (genealogy), identity, and kai (food) harvest for Indigenous Māori communities (Hauraki Gulf Forum 2020). In 2017, seeking to restore balance and uphold mauri, a community-nominated working group released the Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan (Sea Change 2017). The plan proposed four kinds of marine protected areas, including Ahu Moana, a co-governance initiative between iwi (tribes) and local communities, oriented toward shared conservation goals and cultural care.

Yet, implementation has been slow and contested. Despite broad support, Ahu Moana has been challenged by anti-Indigenous backlash, with opponents invoking the idea of “safeguarding democracy” as a veiled resistance to Māori involvement. Some government officials have disparaged co-governance as “[giving] power to people based on who their grandparents were,” arguing that “fish don’t do race” (Gulf Users’ Group 2023). As a result, Ahu Moana pilot projects remain at an impasse.

These tensions point to deeper fractures—living legacies of colonialism, clashes between worldviews, and divergent relationships to Tīkapa Moana herself. My project thus considers how co-governance initiatives like Ahu Moana are not only political but also relational and ontological, raising questions about who the Gulf is and how she is engaged. Rather than viewing the Gulf as a passive backdrop or sea of resources to be exploited, I frame Tīkapa Moana as an ancestor, knowledge holder, and teacher.

In collaboration with iwi members and community organizations—and from my position as a white, non-Indigenous researcher—this project considers:

- Thinking with the Gulf: What methodological commitments guide community-based, decolonial research in Aotearoa? How do different knowledge systems shape research in Tīkapa Moana, and what responsibilities emerge for non-Indigenous scholars within these contexts?

- Governing with the Gulf: How do different actors, such as iwi, academics, and environmentalists, understand their relationships and responsibilities to Tīkapa Moana, and how do these orientations shape political possibilities? What does it mean to govern with Tīkapa Moana, rather than over her? How do co-governance initiatives implicate her mauri and cultural health?

- Healing with the Gulf: What lessons are emerging from Ahu Moana? How might they elevate nonhuman voices and suggest more just models of coastal care in Aotearoa and beyond?

This SRG project lays the groundwork for a long-term research agenda that bridges collaborative coastal governance efforts in Aotearoa and the Pacific Northwest. By understanding how Indigenous-led approaches to marine governance unfold in parallel settler-colonial contexts, I hope to devote my career to supporting more just blue futures across the Pacific. More broadly, this work contributes to the marine social sciences by extending questions of agency, voice, and governance to the moana (sea) herself. It centers Tīkapa Moana as a co-constitutive force in healing and revitalizing her own mauri.

Grounding in Place

Tīkapa Moana is a taonga (treasure), playground, pātaka kai (food storehouse), and ancestor (Hauraki Gulf Forum 2023, 4). Spanning more than 14,000 km2 and bordered by shorelines that house more than 2 million people, her importance in Aotearoa and beyond cannot be overstated. Tīkapa Moana has been of utmost spiritual significance to Māori since the first waka (canoes) navigated her waters thousands of years ago, and these relationships are still reflected in mātauranga (Māori knowledge and worldview), tīkanga (protocols), and practices of kaitiakitanga (environmental guardianship).

Environmentally, she is the seabird capital of the world and home to hundreds of endemic marine species. Economically, Tīkapa Moana and her catchment support the lives and livelihoods of over a third of the country’s population. Her shores host Aotearoa’s largest metropolitan area, busiest commercial shipping port, and extensive tracts of farmland; her waters are leading centers for Aotearoa’s commercial fisheries and aquaculture sectors (Hauraki Gulf Forum 2017). Hundreds of thousands of tourists and recreational users visit her waters every year, swimming, playing, fishing, and appreciating her mana (power).

The author (Dara Craig) diving among silver sweep fish and Ecklonia kelp in Ta Hāwere-a-Maki, Aotearoa’s first marine reserve (Cape Rodney to Oakakari Point Marine Reserve, locally known as the Goat Island Marine Reserve). Photo by Shaun Lee.

Despite her widespread importance, Tīkapa Moana continues to face escalating threats to her mauri. Overfishing, seabed degradation, sedimentation, nutrient runoff, and climate change are among the most pressing issues facing the Gulf. More specifically, according to the most recent “State of Our Gulf” report, tāmure (snapper) and tarakihi (deep sea perch) populations need time to rebuild, koura (crayfish) are practically extinct in heavily fished areas, and tipa (scallop) fisheries have effectively collapsed (Hauraki Gulf Forum 2023).

These species are all important taonga and relatives to Māori, signaling the urgency of reciprocal stewardship efforts. While progress has been made at the central and regional government levels toward rebuilding certain depleted fish stocks and creating new marine protected areas, iwi have continued to lead in implementing localized rāhui (temporary closures), restoring mussel beds, and encouraging healing throughout Tīkapa Moana.

Guiding Methods

Collaboration in Aotearoa has been central to my research. I first connected with iwi and community collaborators in 2018 and have maintained these relationships over the past seven years, visiting for work in 2020, continuing conversations via Zoom in 2021–23, and conducting ethnographic fieldwork in 2024–25. I have been hosted by the University of Auckland, working closely with Daniel Hikuroa, and—in partnership with collaborators—I have engaged in oral histories, storywork, participatory observation, and archival research.

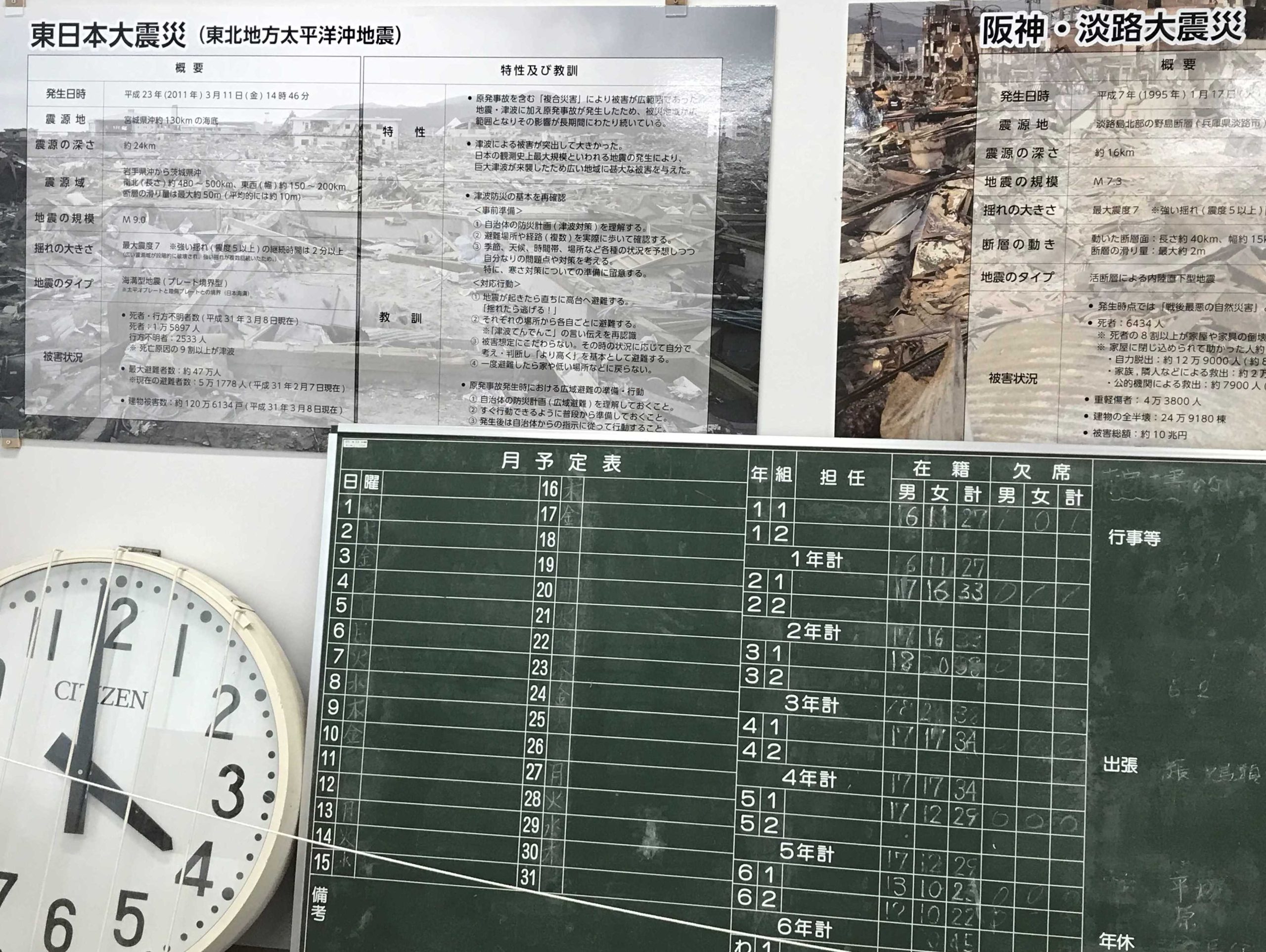

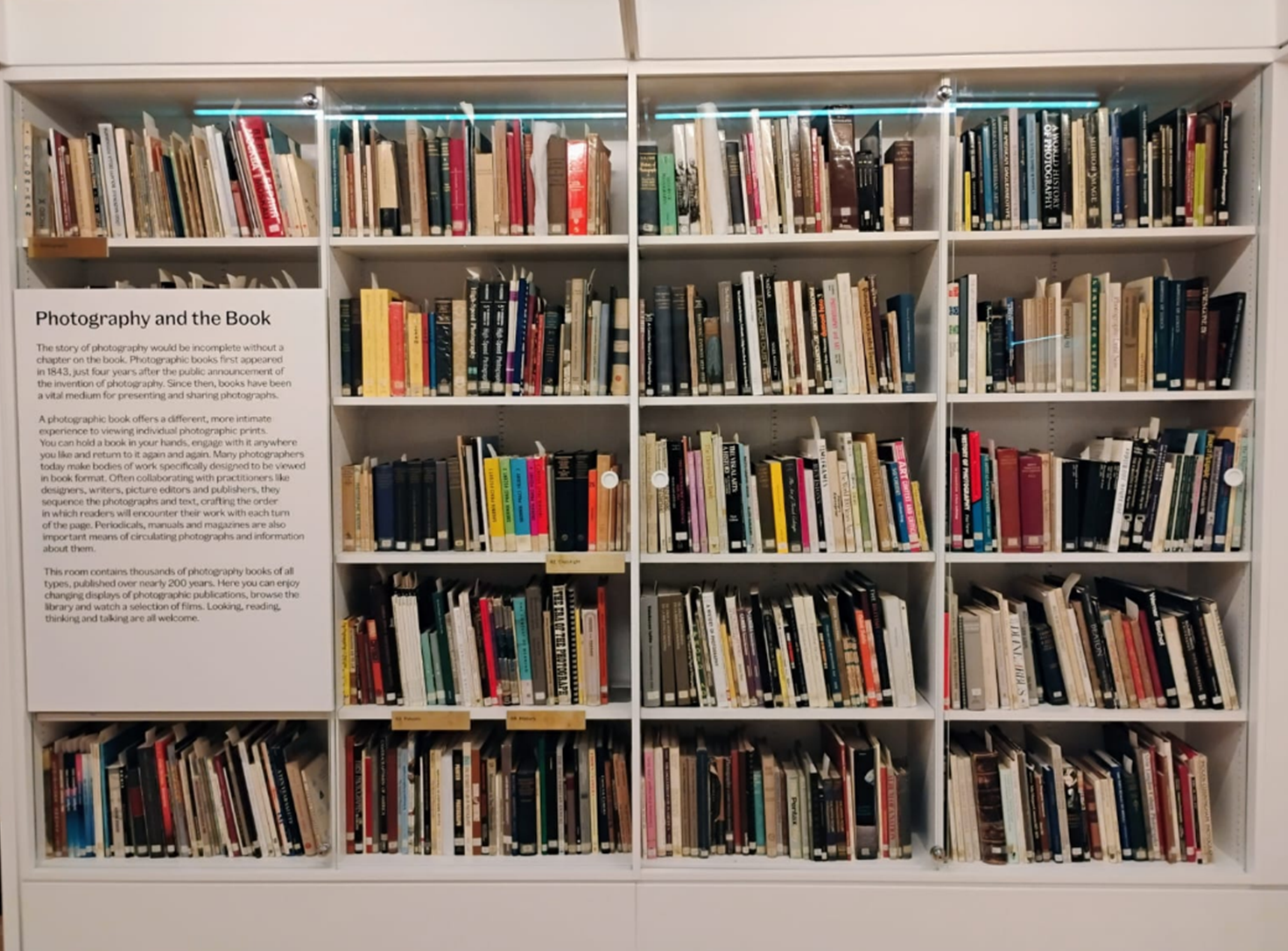

With the support of SRG funding, I recently completed two rounds of ethnographic fieldwork across the corners of Tīkapa Moana, conducting 30 in-depth oral histories with iwi members, government officials, academics, environmentalists, and industry representatives. I also engaged in archival research and document analysis at Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa (the National Library of New Zealand) and volunteered as a diver with a community marine project working to heal the social ecologies and mauri of Tīkapa Moana. I have gratefully been invited to participate in public hearings, government workshops, educational outreach events, community-led marine regeneration projects, scuba dives—both for recreation and scientific surveying—and hui (meetings) at marae (Māori communal meeting grounds), making sure to follow proper tikanga (protocol) regarding consent and respect.

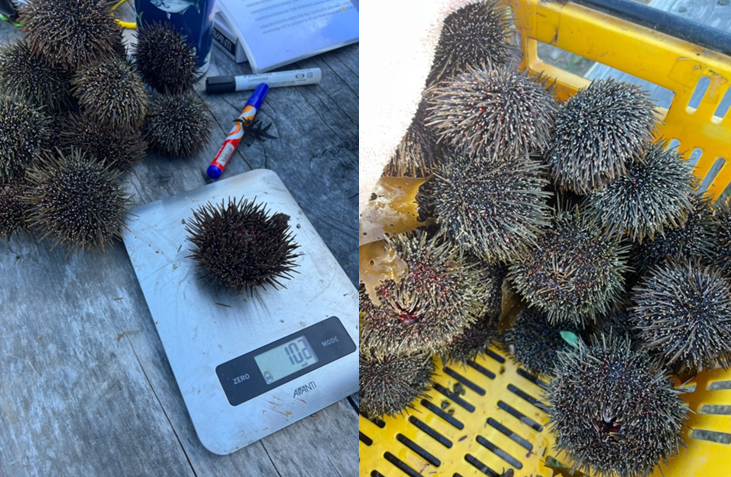

Kina (sea urchins) collected during a “Kelp Gardeners” dive with the Waiheke Marine Project, a community-driven kaupapa (plan, program) that “[coordinates] action for marine regeneration on Waiheke Island.” The goal of the project is to respectfully “remove adult kina to help encourage kelp regeneration” and “[learn] how to be better kaitiaki (stewards).”

I am currently finalizing transcriptions and “making meaning” of data using Kovach’s thematic analysis strategy for Indigenous methodologies (2009, 208), so findings are forthcoming. I am also following up with collaborators to verify transcripts, review preliminary interpretations, and assess written drafts prior to public release. In the coming months, I hope to organize a “share back” visit that continues to prioritize community-centered knowledge-sharing and reciprocity. Together with collaborators, we will organize a series of kōrero (conversations) to share emerging findings, foster cross-cultural conversations, and reflect on the tensions and possibilities for healing Tīkapa Moana moving forward.

Significance and Future Research

Around the world, settler-colonial states are increasingly called to reckon with the cultural and ecological legacies of dispossession—damage that has severed long-standing relationships between Indigenous peoples and the lands and waters they have stewarded since time immemorial (e.g., Layden et al. 2025; Leonard et al. 2023; Liboiron 2021). Some nations have begun to revise their governance frameworks in support of Indigenous leadership—not only in Indigenous-held territories but also on public lands and waters through shared stewardship, co-management, and co-governance arrangements (e.g., Diggon et al. 2021; Kooistra et al. 2022; Peart 2018; Reid et al. 2020). While these models have proliferated in management and policy discourse, much remains unknown about how they unfold in practice, and most importantly, how they (re)shape relationships between people, institutions, and living ecosystems.

Enclosure Bay on Waiheke Island is sheltered by large rocks and is home to a number of Waiheke Marine Project actions, including Kelp Gardeners dive and snorkel events.

This project situates Ahu Moana within these broader shifts, exploring not just how governance happens but what it unsettles and what/who it might restore. The work responds to growing calls for community-engaged, place-based governance approaches by foregrounding Tīkapa Moana not as an object of policy but an active co-governor and collaborator in regeneration (e.g., George and Wiebe 2020; Lobo and Parsons 2023; Shefer and Bozalek 2022). It offers a relational framework for thinking with marine ecosystems as political, social, and ancestral actors.

While some findings are inherently place-based and contextually specific, the project lays the groundwork to eventually compare collaborative governance in Aotearoa and the Pacific Northwest that could offer insights that resonate across the Pacific. At a moment when co-governance is politically contested in Aotearoa and globally, I hope to elucidate the relationships between collaborative governance, fractured social ecologies, and repair. It encourages future building that begins not from a push for more technocratic solutions but from the recognition that Tīkapa Moana and seascapes around the world are beings in need of restored relationship.

References

Diggon, Steve, Caroline Butler, Aaron Heidt, et al. 2021. “The Marine Plan Partnership: Indigenous Community-Based Marine Spatial Planning.” Marine Policy 132: 103510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.04.014.

George, Rachel Yacaaʔal, and Sarah Marie Wiebe. 2020. “Fluid Decolonial Futures: Water as a Life, Ocean Citizenship and Seascape Relationality.” New Political Science 42 (4): 498–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393148.2020.1842706.

Gulf Users’ Group. 2023. “Where the Main Parties Stand on Co-Governance of the Hauraki Gulf.” Last modified September 1, 2023. https://www.gulfusers.org.nz/media-releases/where-the-main-parties-stand-on-co-governance-of-the-hauraki-gulf.

Hauraki Gulf Forum. 2020. “State of Our Gulf 2020.” https://gulfjournal.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/State-of-our-Gulf-2020.pdf.

Hauraki Gulf Forum. 2023. “State of Our Gulf 2023.” https://gulfjournal.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SOER-online.pdf.

Kooistra, Chad, Courtney Schultz, Jesse Abrams, and Heidi Huber-Stearns. 2022. “Institutionalizing the United States Forest Service’s Shared Stewardship Strategy in the Western United States.” Journal of Forestry 120 (5): 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1093/jofore/fvac010.

Kovach, Margaret. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. University of Toronto Press.

Layden, Tamara, Dominque M. David-Chavez, Emma Galofré García, et al. 2025. “Confronting Colonial History: Toward Healing, Just, and Equitable Indigenous Conservation Futures.” Ecology & Society 30 (1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-15890-300133.

Leonard, Kelsey, Dominique David-Chavez, Deondre Smiles, et al. 2023. “Water Back: A Review Centering Rematriation and Indigenous Water Research Sovereignty.” Water Alternatives 16 (2): 374–428.

Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press.

Lobo, Michele, and Meg Parsons. 2023. “Decolonizing Ocean Spaces: Saltwater Co-Belonging and Responsibilities.” Progress in Environmental Geography 2 (1–2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2753968723117923.

Peart, Raewyn. 2018. “A ‘Sea Change’ in Marine Planning: The Development of New Zealand’s First Marine Spatial Plan.” Policy Quarterly 13 (2). https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v13i2.4658.

Reid, Andrea J., Lauren E. Eckert, John-Francis Lane, et al. 2020. “‘Two-Eyed Seeing:’ An Indigenous Framework to Transform Fisheries Research and Management.” Fish and Fisheries 22 (2): 243–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12516.

Sea Change. 2017. “Sea Change Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan.” https://seachange.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/5086-SCTTTP-Marine-Spatial-Plan-WR.pdf.

Shefer, Tamara, and Vivienne Bozalek. 2022. “Wild Swimming Methodologies for Decolonial Feminist Justice-to-Come Scholarship,” Feminist Review 130 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/01417789211069351.