Since 2006, the Sylff Chamber Music Seminar has been held jointly by the Juilliard School in New York, the University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna and the Paris Conservatoire. A special support program for the three institutions is funded by the Tokyo Foundation, enabling approximately 14 fellows to gather at one of the host institutions each year, rehearsing and receiving coaching together before performing a final concert for a local audience and members of the host institution. The goal of the seminar is to foster long-term professional relationships among fellows and institutions and to expose them to different performing and teaching styles as well as to develop young leaders and artist-citizens of the 21st century.

Tokyo Foundation Program Officer Tomoko Yamada provides a report of the ninth seminar, held in New York in January 2015.

* * *

All participating Sylff fellows and Tokyo Foundation members.

From January 4 to 13, 2015, the Juilliard School hosted eight Sylff musicians from the University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna, and the Paris Conservatoire. These musicians joined four professors and five Juilliard Sylff fellows for a week of chamber music, culminating in a vibrant concert at the renowned Paul Hall in Lincoln Center, the artistic epicenter of Manhattan. The musicians, originally from France, Austria, Australia, China, and Lithuania, performed works by Vissarion Shebalin, John Harbison, and Brahms.

A Tough Beginning

Things got off to a less-than-ideal start when the musicians from Paris arrived a day late and without their luggage after their plane was cancelled. New York City at minus 10 degrees Celsius is not the place to be when you have no clothes except what you are wearing. Even more worrisome for the musicians, this delay meant the potentially devastating loss of a whole day of rehearsal time—no small matter when the schedule allowed only a week or so from the first meeting to final performance.

The musicians ended up going straight from the airport into lessons and rehearsals. One of the fellows recalled: “Not having a break and seeing the rooms the moment we arrived from a two days long and complicated flight and having a lesson so early in the week. . . It would have been nice to practice a little more with all five (group of five among the three institutions who were brought together for the first time to play the Harbison Quintet) of us together before meeting the professor. But he was okay, comprehensive and helped us a lot with our practice (maybe it’s a cultural difference. . . ) The role of the teacher is more like a coach in the USA, helping the student to find a way to be independent. In Paris the teacher is waiting for a result, a concert version, more or less.”

This exposure to cultural differences is one of the strengths of the seminar. Guest fellows are exposed to different styles of teaching and practice that open their eyes to new perspectives. Generally speaking, the European master-teacher sees the student as an apprentice, who needs detailed instructions leading to an expected outcome. The American teacher tends to be more flexible, offering a blend of concrete guidance and greater openness to alternative approaches. Many European teachers believe it is their job to steer the student to the perfect performance. American teachers want their students to find their own voice, allow their soul to find expression in the music, even if the result is quite different from how the teacher would play it.

The Coaching Sessions

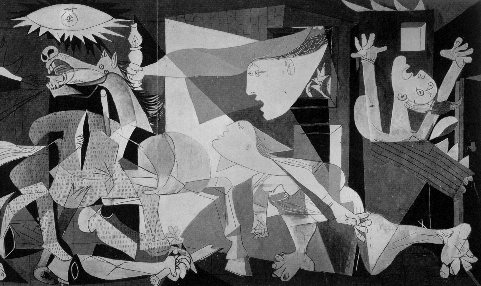

A coaching session for the Harbison quintet.

I enjoyed a rare opportunity to observe the coaching sessions. I was struck by the energy and passion of the coaches. The fellows were obviously taken in as they were scribbling away frantically on their scores, determined not to miss a word from the coaches.

Rehearsals were generally run by the host fellows from Juilliard, who had the delicate task of balancing the rigorous rehearsals with varying needs of guest fellows. Some were suffering from jetlag, while others were anxious to get a taste of the city. Yet others needed to grab some clothes at H&M because their luggage still hadn’t turned up. The host fellows tried to strike a balance between organizing intense rehearsals and making sure that their guests got some free time. I knew from the previous two seminars that each of the three institutions has its own styles of practice and rehearsal. The American approach seems to give the students a large degree of freedom to determine what they need to rehearse and when.

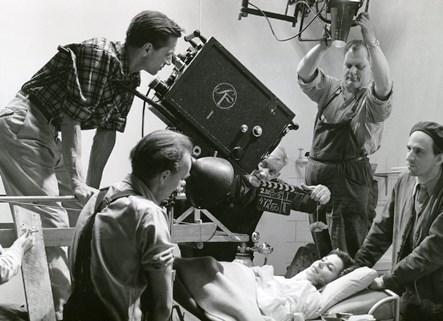

Pre-college Students

Giving advice to the pre-college students.

Amid the tightly knit coaching, rehearsal and practice, Bärli Nugent, who is assistant dean and director of chamber music at Juilliard and works as the orchestrator of the Sylff Chamber Music Seminar, managed to squeeze in a session on Saturday afternoon with a group of Juilliard pre-college students and the wind instrument fellows. “Juilliard pre-college students” are teenagers ranging from 10 to 18 who have a serious interest in music-playing and take pre-college classes at Juilliard in preparation for a possible music career. This was a magnificent idea. Fellows got a chance to share their experience and expertise as musicians with younger people. The pre-college teenagers started by performing one movement of the Harbison wind quintet, followed by the Sylff fellows playing the same piece. This was followed by a lecture by a fellow on French bassoon, which is rarely played outside France. Finally, there was an informal discussion among the fellows and pre-college students.

One could see that this was a mind-boggling experience for the pre-college students. I could observe their seriousness in the way they listened intently to the fellows’ performance, silently taking notes on the scores on their lap. During the informal discussion, one of the fellows, a flutist, demonstrated one of his favorite practicing techniques. He played an Irish folksong, beating the rhythm with his foot, and explained that this helps the body to relax and play better. One of the pre-college students, a young Asian girl who had been watching intensely, seemed astonished by this revelation. She had always concentrated on practicing the perfect technique for classical flute, and this more relaxed approach seemed to open her eyes to a new perspective.

The session with pre-college students was also valuable for the fellows, one of whom described it as a highlight of the entire seminar. “The best moment was when we met the pre-college students, listened to them, and played for them, and especially the talk we had together about what music means for us, our futures, our passion” That was the most powerful aspect of the entire seminar for him. As well as learning many new things during the seminar, the fellows also had a valuable opportunity to teach something to local young musicians who may follow in their footsteps. It was a chance for all the fellows to reexamine their own passion for music.

Finding the Music

Sylff fellows including Meta Weiss, standing center, with Shebalin’s grandchildren.

As the days went by, the music gradually moved closer to perfection. I realized that the fellows were not simply learning and practicing the music. Rather, they were interpreting the score and finding the music by fusing the differing musical opinions among them. This was particularly true for Shebalin’s String Quartet No. 9. This piece was proposed by Juilliard’s Sylff fellow, Meta Weiss, whose doctoral research had focused on how Soviet politics and the composer’s medical condition manifested itself in his music. Weiss's research in Moscow was funded in part by the Sylff Research Abroad program. Thus, for the first time, research and performance were brought together with Sylff support. Doing this was not easy, however. The score that Weiss had brought back from Moscow was incomplete and there was little additional information available on the music. Weiss worked together with Susanne Schäffer (Vienna) and Clare Semes (Juilliard) on violins and Marina Capstick (Paris) on viola to interpret the score and completed the music for the performance.

Clare Semes reflected: “Learning the music of Shebalin was a very powerful experience. My colleagues and I had the privilege of learning, with great help from Weiss, the ninth quartet of this little-known composer. The journey from the first rehearsal to the final performance was very impactful because I was able to discover the music of Shebalin with new and old friends from Juilliard, Vienna, and Paris.”

The Concert

(From left to right) Clare Semes, Suzanne Schäffer, Marina Capstick, and Meta Weiss performing the Shebalin quartet.

The concert began with the Shebalin quartet. Before the performance, Weiss provided the audience with some background on the remarkable story of the piece. Shebalin’s grandchildren were present in the audience as the piece received its American premiere.

(From left to right) Samuel Bricault, Julia DeRosa, David Raschella, Lomic Lamouroux, and Georgina Oakes performing the Harbison quintet.

This poignant performance was followed by John Harbison’s quintet for winds. Harbison is a contemporary New York composer who remains little known outside the United States. Most of the fellows had never played his music before. The effort they made to grapple with this unfamiliar music was well rewarded in a performance that was intense and at times playful.

The concert reached its grand finale with Brahms’ majestic Piano Quartet in G Minor, a performance that was greeted with roaring applause from the audience.

(From left to right)Yun Wei, Marc Desjardins, Gleb Pysniak, and Ying Xiong performing the Brahms piano quartet.

This comment by a fellow who has participated in seminars at all three host institutions sums up the program best:

“Chamber music is a beautiful musical form. It not only allows each musical personality to shine individually but also makes possible a wonderful blending and shaping of colors though a variety of instrumental combinations. These seminars have given me an opportunity to understand my own musical voice by not just exposing me but immersing me in new musical cultures. Each immersion gave me the possibility to reflect upon my own approach to music. To identify similarities and differences, to gather new ideas and tools.

“But, most importantly, coming away from these seminars over the past three years, I can feel that they have mapped my development from being a student seeking a teacher’s guiding path into an artist with my own personality, voice and integrity.”

In Closing

Every great program owes its success to the people working behind the scene to make it happen. I would like to end this report by expressing my sincere thanks to Bärli Nugent of Juilliard, Gretchen Amussen (director of external affairs and international relations, Paris Conservatoire) and Dorothea Riedel (project manager, University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna) whose efforts have helped this program to flourish.