In Jordan, legal reforms have been promoted to achieve gender equality, which have led to improvements in female participation in education. However, there is still a big gap to achieving women’s empowerment in a practical sense, as cultural and religious norms encouraging gender inequality prevail in the society. The norms prevent women from social and political participation and even justify gender-based violence toward women. Dr. Tayseer Abu Odeh, a 2007 Sylff fellow at the University of Jordan, held a conference on July 16, 2019, at the University of Jordan to tackle the social issue by rethinking social, legal, and healthcare services. The conference was funded by Sylff Leadership Initiatives (SLI).

* * *

Background and Objectives

It is my great pleasure to say that this conference was the first one organized in the Middle East by Sylff Leadership Initiatives, as one of the substantial and key conferences that seek to point to future directions in the field of gender studies and gender-based violence in Jordan. The conference is intended to address and examine the very implications of the term gender-based violence, which is defined in Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Actions (Inter Agency Standing Committee, 2015) as follows: “any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on socially ascribed (i.e. gender) differences between males and females. It includes acts that inflict physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion, and other deprivations of liberty. These acts occur in public and in private.” With that in mind, this conference aims at addressing gender-based violence by assessing and rethinking social, legal, and healthcare services in Jordan.

The conference was held on July 16, 2019, at the University of Jordan.

According to a study conducted in 2015 and published in 2016 by United Nations Women titled “Strengthening the Jordanian Justice Sector’s Response to Cases of Violence against Women,” only 3% of victims of gender-based violence in Jordan seek official support from the police after being traumatized by any act of violence. Similarly, National Council for Family Affairs conducted an important report titled “Status of Violence against Women in Jordan” in 2008. It indicates that National Forensic Medicine Center in Jordan “deals with an average of 700 cases of sexual assault against women annually” and that “the number of murdered women recorded was 120 in 2006, including 18 cases classified as crimes of honor.” Ironically, the actual cases of physical and emotional abuse outnumber these statistics for many sociopolitical and cultural reasons. As a tribal and conservative society, many Jordanian families do not report these cases to protect their superego and collective image at the expense of the victim’s individual trauma.

The audience consisted of people from all walks of life.

Opening Remarks

Dr. Abeer Dababneh, director of the Center for Women’s Studies at the University of Jordan, opened the conference by stressing the significance of the event in raising the bar of social and gender consciousness in Jordan in terms of the available services offered by the three major sectors in Jordan: law, justice, and social development.

The president of the University of Jordan, Dr. Abdul-Karim Al Qudah, delivered a speech on how the University of Jordan plays a crucial role in empowering women and giving them a space for sociopolitical representation. He argued that the university is meant to be a feminist and intellectual hub for women’s equality, justice, and creativity, where many female students and teachers have a local and global reach and outshine their counterparts in every field of knowledge.

Moreover, Justice Minister Bassam Talhouni placed an emphasis on the significant role being played by the Ministry of Justice to fight a number of structural obstacles that confine and hinder gender equality. Although Jordan has witnessed some degree of local progress on gender issues, gender-based violence in Jordan is still a serious issue that should be resisted by national institutions at all levels.

Opening remarks.

Conference

The conference held on July 16, 2019, at the University of Jordan sought to develop and implement a more dynamic and practical strategy and method to protect Jordanian survivors who have been repeatedly traumatized by gender-based violence. Accordingly, the conference consisted of four panels:

Panel 1. Legal and Justice Services in Jordan

Panel 2. The Role of National, International, and Civil Society in Jordan

Panel 3. Gender-Based Violence in the Healthcare Sector

Panel 4. Gender-Based Violence in the Social Development Sector

In the first panel, all panelists stressed the way in which the sociocultural and legal contexts impact the whole process of gender-based prosecution in Jordan. The panelists also addressed how the Family Protection Program and other government institutions facilitate legal services for gender-based violence survivors. Meanwhile, they also underscored the limitations of these institutions and how such limitations should be treated locally.

The second panel was premised on the role of national, international, and civil society in Jordan. The panelists highlighted the significant role played by the National Council for Family Affairs and other government and nongovernment institutions vis-à-vis the multiple family protection projects in Jordan. They also emphasized the urgent need to revise the legal system and the alternative ways that this could be carried out to strengthen cooperation between these institutions toward fighting gender-based-violence in Jordan. In a similar vein, the third panel examined the multiple healthcare services offered by the Ministry of Health for victimized women in Jordan. Furthermore, the panelists concretely addressed the cultural and institutional flaws that hinder the process of fighting violence against women in Jordan. The panelists of the last session attempted to explore the way in which the social development sector engages in several rehabilitative counseling programs by training legal employees who are in charge of gender-based violence cases in Jordan. The panelists shed light on the psychological and professional competence of public employees.

The second panel, “The Role of National, International, and Civil Society in Jordan Legal and Justice Services in Jordan.”

Open Discussion

Each panel had an open discussion, in which many members of the audience gave compelling and engaging questions and remarks on gender-based violence in Jordan. For instance, an Egyptian activist attempted to challenge the dominant cultural paradigms of gender duties and roles that have been dogmatized and maintained by religion, government, and culture in Jordan. Another graduate student of gender studies was curious to understand the cultural and institutional circumstances that have shaped gender trouble in Jordan. Dr. Tayseer Abu Odeh, the organizer of the conference, responded to this question by arguing that gender trouble emanates from the cultural and social dogma of stereotypes and some religious misinterpretations that deem gender roles as being fixed and unchangeable. Thus, these dogmatic gender roles should be dismantled and challenged by reforming educational pedagogy, incorporating the most up-to-date research findings on gender studies into educational curricula in terms of the cultural and political context of gender-based violence in Jordan, gender equality, and statistical cases.

Final Recommendations Suggested by Participants

The participants agreed on a set of feasible and compelling recommendations that meet the most pressing issues of gender-based violence in Jordan. The media, for instance, should play a crucial role in sustaining and disseminating a profound discourse that offers a counternarrative to gender-based violence that should include updated statistics on all acts of gender-based violence in Jordan, hosting influential feminists to discuss major issues of gender-based violence, and evaluating the kinds of services offered by the three sectors of healthcare, justice and police, and social development. Similarly, the Ministry of Higher Education should be obliged to incorporate a new course on gender-based violence through which university students will be exposed to a wealth of legal, cultural, and epistemological knowledge on gender-based violence in Jordan regarding the discursive quantitative and qualitative circumstances that motivate any act of violence against women in Jordan. Moreover, the panelists stressed the significance of creating a professional national monitoring system through which the risk of gender-based violence in Jordan could be identified and assessed. Several panelists suggested a vibrant institutional and legal collaboration among all government and nongovernmental organizations that are in charge of survivors and victimizers of gender-based violence.

Dr. Tayseer Abu Odeh also stressed the importance of establishing a research database that would function as a professional research platform encompassing all reports, documents, and stories that address and document gender-based violence and assess national services in Jordan. A number of panelists argued that founding a national counseling office for gender-based violence at all universities should be a national priority. Drawing on the agenda of this conference, some of the scholars recommended outlining and endorsing a national manifesto agreed upon by all governmental and nongovernmental institutions that are in charge of fighting gender-based violence in Jordan. It would be a national and academic manifesto that legislates and outlines the national and humanitarian roles, duties, authorities, and agendas among various national partners that are concerned with gender-based violence.

Conclusion

It has been noticed that the vision of gender-based violence held by the government and bureaucracy in Jordan is somewhat limited and dogmatic. Several participants standing for government institutions were obsessed with a discourse of denial in which their findings seemed to underestimate the serious risk of gender-based violence in Jordan. Conversely, independent scholars and gender activists and leaders expressed an opposing view that challenges the one suggested by government representatives. With that in mind, a number of panelists suggested putting forward and organizing another forum in the near future that would reexamine gender-based violence in Jordan from a radical sociopolitical perspective. Drawing on Lila Abu-Lughod’s feminist paradigm, our anticipated conference would be mainly premised on the intersections between globalism, gender politics, and the political economy.

The conference caught the attention of many international and national feminists, scholars, lawyers, activists, senators, officials, policy makers, and academics. It also drew considerable interest from the media in Jordan. The conference was covered by the most influential and popular Jordanian media outlets that include, but are not limited to, the Jordan Times, Petra News Agency, Alrai, Addustour, Alghad, and the University of Jordan’s website. All media reports released on the conference noted the significance of the conference in fighting all forms of gender-based violence in Jordan.

Taking the major proceedings and recommendations of the conference into account, I would argue that gender-based violence in Jordan is still a serious sociopolitical and cultural problem that should be faced and resisted by all levels of the private and public sectors. In a nutshell, there should be a substantial strategic collaboration between all government and nongovernmental institutions. With that in mind, in my capacity as a Jordanian writer, activist, and intellectual, I am determined to keep fighting this crisis in every possible way and exert tremendous efforts to raise cultural and social consciousness about gender-based violence in Jordan.

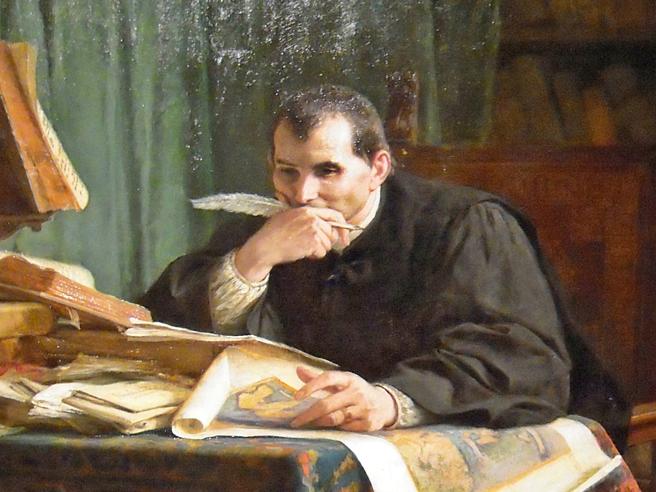

Dr. Tayseer Abu Odeh, an organizer of the conference.

References

“Strengthening the Jordanian Justice Sector’s Response to Cases of Violence against Women,” United Nations Women, 2016.

* * *

Detailed arguments made in the panels are summarized below.

Panel 1: Legal and Justice Services in Jordan

The first panel of the conference was titled “Legal and Justice Services in Jordan.” Asma Khader, a leading human rights lawyer and former minister of culture, addressed the way in which gender-based prosecution is carried out in Jordan. Khader shed light on the social, cultural, and legal contexts of juridical prosecution in Jordan. Khader argued that many prosecutors who are in charge of gender-based violence cases and the implementation of the legal system lack sufficient legal, sociopolitical, and cultural literacy and professional training.

The second speaker, Reem Abu Hassan, a leading human rights lawyer and former minister of social development, discussed gender violence from a legal perspective. Drawing on her perspective, Abu Hassan also contended that cultural and social stereotypes are considered to be one of the most pressing issues that have shaped the various structures of gender trouble in Jordan.

The third speaker of this panel was Fakhri al Qatarneh, director of the Family Protection Program. Qatarneh examined the role of the program in facilitating the multiple services that are offered for gender-based violence survivors in Jordan. Unlike Khader and Abu Hassan, Qatarneh argued that the increasing number of complaints that have been recently reported to the Family Protection Program is an indicator of people’s awareness of gender-based violence in Jordan. Qatarneh’s argument sounded somewhat contradictory, as it confirmed an ideological discourse of denial that has been sustained by government officials whenever they address gender-based violence in Jordan.

Panel 2: The Role of National, International, and Civil Society in Jordan

The second panel addressed the role of national, international, and civil society in reinforcing sufficient and effective services that have to do with gender-based violence in Jordan. The first speaker was Yara Al Deer, a researcher at the Arab State Regional Office of the United Nations Population Fund. Al Deer pointed out that national and local institutions of healthcare, justice, and social development sectors should collaborate and cooperate more effectively to implement a range of feasible procedures of social, psychological, and legal support for survivors.

The second speaker, Dr. Mohammad Fakhri Meqdady, secretary general of the National Council for Family Affairs in Amman, highlighted the role of the NCFA in fighting gender-based violence in Jordan in light of various social and political transformations. Meqdady noted that a family protection project was initiated to protect a large number of survivors in Jordan. He also stressed the importance of collaboration among government and nongovernmental institutions that fight gender-based violence in Jordan from statistical, procedural, and legal perspectives.

Dr. Salma Nims was the third speaker of this panel. She is secretary general of the Jordanian National Commission for Women in Jordan. She addressed the dynamic and vital way in which the political and social roles of the Jordanian National Commission for Women are played. According to Al Nims, the commission is in charge of the following responsibilities: ensuring a convenient and applicable environment, revising the legal system, opening up a powerful and face-to-face dialogue with the government, building up an effective dialogue with the civil society in order to agree on specific legal amendments and revisions, and enforcing an active form of cooperation among all government and nongovernmental institutions to fight gender violence in Jordan. Such a dynamic role, however, is diminishing due to lack of institutionalism and bureaucracy.

Dr. Ibrhim Aqil, director of the Noor Al Hussein Center for Family Health Care, was the last speaker of this panel. Aqil explored how civil society can imagine and offer alternative and feasible services for survivors of gender-based violence in Jordan. Aqil juxtaposed the interplay between data of gender-based violence, getting access to these data, and the right to get adequate and efficient services. He also placed an emphasis on the indispensable nature of multiple services that should be offered for survivors. These services include protective, educational, legal, administrative, social, and psychological procedures.

Panel 3: Gender-Based Violence in the Healthcare Sector

The third panel was titled “Gender-Based Violence in the Healthcare Sector.” Dr. Malak Al Ouri, director of Women’s Healthcare in the Ministry of Health, examined the role of the Ministry of Health in the reinforcement of health services for traumatized women in Jordan. Al Ouri discussed how the family violence department plays a vital role in handling gender-based violence issues in Jordan. In addition, a number of professional committees have been initiated by the ministry to follow up on all cases of gender violence in Jordan and make sure that each case is reported and documented immediately and rigorously. However, there is a built-in flaw in the institutionalized and scholarly documentation of such kind of cases arising from governmental bureaucracy, cultural stigmatization, and lack of cooperation between government and nongovernmental institutions regarding gender-based violence.

Dr. Maha Darwish, an expert on gender-based violence with the United States Agency for International Development, also addressed alternative and feasible services to rehabilitate gender-based victimizers from a psychosocial perspective. Darwish suggested psychological procedures to rehabilitate victimizers and ensure a professional training program designated by the Ministry of Health and other local institutions.

Panel 4: Gender-Based Violence in the Social Development Sector

Panel four was concerned with gender-based violence in the social development sector. Amer Hiasat, director of the Social Development Program in Amman, discussed the multiple ways in which social protection for gender-based victims is maintained and carried out by the Ministry of Social Development. Hiasat asserted that the ministry has a crucial role in offering beneficial services for survivors of gender-based violence in Jordan. Nevertheless, this role is still flawed due to multiple bureaucratic and institutional inconsistencies.

Meanwhile, Eva Abu Halawa, director of Mizan Organization for Women’s Rights, put forward a number of suggested methods that civil society should use to protect survivors of gender-based violence. She contended that raising gender consciousness among people is a national priority that should be taken into account in fighting gender-based violence in Jordan. She also suggested creating more specialized counseling departments for training legal prosecutors and employees who handle cases of gender-based violence.

The last speaker of this panel was Dr. Amal Al Awawdeh, a professor of gender studies at the Center for Women’s Studies, University of Jordan. She interrogated the professional and technical competence of government social specialists who are in charge of handling gender-based violence in Jordan. Her findings are premised on the lack of effective professionalism among government social specialists and how such a flaw impacts social and counseling intervention and protective programs that have been employed by the Ministry of Social Development.